15 Oct 2015

When I went to the recent 2015 International Permaculture Convergence, one workshop I really wanted to go to was about permaculture and prisons. I couldn’t go though, as I had to be somewhere else. So I subsequently got in touch with Nicole Vosper, who led that workshop, and interviewed her instead! Nicole lives in Somerset, and runs a website called emptycagesdesign.org. As an ex-prisoner who is actively involved in permaculture, her work focuses on the bridge between the two. I started out by asking her why she feels that the prison system needs a rethink:

“I did a 3 ½ year prison sentence when I was 21. Twenty one months was in a private prison in Middlesex. That was in a backdrop of long-term organising for different social justice projects and campaigns and struggles.

My perspective on the prison system is that it’s inherently violent. Even with bigger cells or more adequate healthcare or more visits, or more education and training, or gardens in prisons, all these things that people throw around; even with all of those reforms I believe it’s inherently violent, because I believe that act of caging a human being is violent. Prison abolition, which is something I organise for, is about looking at what other solutions are there to the social and economic problems that the prison system is allegedly meant to be solving.

In what ways does the prison system, in your opinion, have unfairness designed into it fundamentally? Is it a fundamentally unfair design?

As a design, the prison system is incredibly effective in the sense of who it’s serving. It’s serving the State, and it’s also serving the hierarchies that exist in our society. Anyone who is engaged in any sort of social change work will probably see prison or repression as a limiting factor or a fear to overcome to push for more change. Prisons are fundamental to maintaining this social order in our society and they’re really essential to maintaining this class-based system that we have, especially in the UK.

As a design, the prison system is incredibly effective in the sense of who it’s serving. It’s serving the State, and it’s also serving the hierarchies that exist in our society. Anyone who is engaged in any sort of social change work will probably see prison or repression as a limiting factor or a fear to overcome to push for more change. Prisons are fundamental to maintaining this social order in our society and they’re really essential to maintaining this class-based system that we have, especially in the UK.

There’s an author called Karlene Faith who wrote a book called ‘Unruly Women’ about women in prison, and she describes prisons as places “where all the injustices converge”; so prisons perpetuate inequalities in the sense of race. People of colour are highly criminalised, have totally disproportionate sentences, especially foreign nationals and this new wave of – well it’s not new – racism towards immigrants. Immigrants are increasingly becoming criminalised and filling up our prison system. That’s no accident.

Prisons harm disproportionately queer, gay communities, the homeless, generally just the working class. The war on drugs and all these other things that the state holds as keeping us safe, the ‘us’ being this privileged minority, is actually false, and I feel that prisons are definitely perpetuating more harm than they are preventing or solving.

It’s quite a step from that to the idea of abolishing prisons altogether. Is there not an argument that actually prison keeps most people safe from some really violent, unpleasant characters; that there are some people for whom prison is a necessary thing?

I understand that prison abolition is a challenging perspective, especially if people are new to these issues. When I facilitate workshops around this field, I always ask people “what makes you feel safe?” “What keeps you safe, or your community safe?” The things that come out of those workshops, and these are workshops with all sorts of people: ex-prisoners, different community groups, even permaculture people at these conferences, the same pattern has come up again and again.

Access to healthcare, accountability if someone has experienced harm… If someone has experienced rape or abuse, or murder or violence then they need to feel some level of accountability with the perpetrator of that harm. Indigenous communities all over the world have managed to function without the use of huge state-run prisons. It’s a fallacy that we couldn’t organise our society without them.

I always bring it back to what keeps you safe, and most people say if they’ve experienced harm that they want a supportive group of friends around them. They want to have that communication with the perpetrator eventually. They want to feel immediately safe in their environment. So for me, the link between prisons and permaculture is actually redesigning our society and building communities that can really meet people’s needs so you don’t have people having to commit crime, using that discourse of crime to actually meet their own needs.

Most people in prison are there for economic reasons, or because their communities are criminalised. The criminalised communities that are in prison are the ones that are experiencing the most harm. So you chat to anyone in jail and they’re the ones that have experienced being mugged, being burgled, sexual and financial abuse, everything. It’s not really working for anyone. The people who experience the harm the most are the ones that are filling up our prisons.

You mentioned that you were in a private prison. One of the things that a lot of people listening to this might not be aware of is the extent to which the prison service is now a private commercial operation. Could you say a little bit about that and how that affects who prison serves and what the experience is for people on the inside?

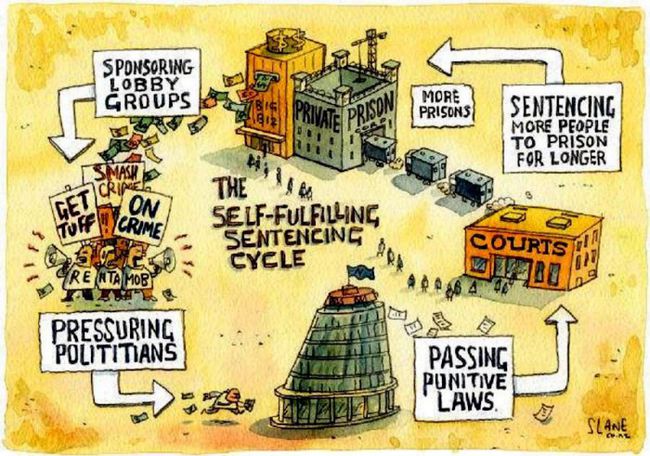

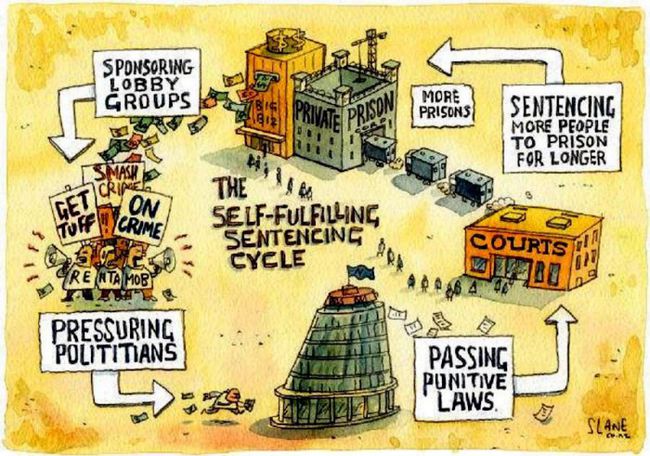

This term the ‘Prison Industrial Complex’ has emerged in the last couple of decades to describe the more complex web of relationships that underpin the prison system. It’s never just been the state that runs prisons, but increasingly it is private companies that are running institutions. For example, all of the immigration detention centres in the UK are run for profit by private companies. What’s problematic about this isn’t just the ethics involved, actually profiting and serving your shareholders through caging certain groups of people; it’s also that the private prison industry have a lot of power and lobbying power so they can actually change our whole criminal justice system because they can put pressure to change different sentences and make reforms and stuff, so it changes the whole landscape of our criminal justice system.

In terms of private prisons, I’m not pro-state prison by any means at all, but there are definitely some differences and patterns. For example, of the top five prisons in the UK with the highest rates of self-harm last year, four of them were private prisons. You have this effect where companies are trying to cut corners because that’s their business interest and that obviously is going to affect prisoners, so that will reduce staffing ratios, making prisoners a lot more generally unsafe, higher levels of abuse between staff. In the prison I was in, 4 or 5 different officers had been sacked after I left for sleeping with women in the prison.

This level of abuse is rife in UK jails. There are obviously contracts with private companies that are directly profiting from the labour of prisoners, companies like Virgin or DHL, they are all making money by paying prisoners a maximum of £25 a week, and that’s a job that could have gone to someone on the outside for minimum wage or more. It’s completely shocking that they’ve created this system to profit from something that is so exploitative and harmful, and it is destroying communities by removing people from those communities. We’ve had horrific things of capitalist exploitation, war, everything else, but I do think there is something really screwed up about making money from actually caging people.

What, for you, would prison abolition look like? If people were guilty of violent crimes or whatever, what would be the ideal way of managing that, or treating that?

The most important thing is that there’s no one solution to anything. What would work for me or maybe my community wouldn’t necessarily work for another. So it’s about having this constellation of alternative strategies to respond to harm, just like indigenous cultures have got all variety of tools and community processes to respond to harm in their communities. We’d have to do that work and that design work and that practice and that development to actually be able to respond to these issues.

A lot of those tools already exist, especially in more anarchist subcultures. We have things like ‘safe spaces agreements’ and accountability processes. There’s a model that has come out of North America called ‘Transformative Justice’ which emerged due to the needs of survivors of sexual violence wanting to not endanger the perpetrators of that violence and subject them to the criminal justice system but actually to look at alternatives and to support them to transform their behaviour, so everyone is transformed by that process; it’s not just a case of restorative justice where you’re restoring the same power imbalances that perpetuate the harm.

A lot of those tools already exist, especially in more anarchist subcultures. We have things like ‘safe spaces agreements’ and accountability processes. There’s a model that has come out of North America called ‘Transformative Justice’ which emerged due to the needs of survivors of sexual violence wanting to not endanger the perpetrators of that violence and subject them to the criminal justice system but actually to look at alternatives and to support them to transform their behaviour, so everyone is transformed by that process; it’s not just a case of restorative justice where you’re restoring the same power imbalances that perpetuate the harm.

For me, prison abolition is one massive creative design opportunity of how can we keep our community safe, and what tools and processes can we imagine to respond to harm in a way that doesn’t give power to the state or lock people behind bars. In terms of this violent minority that we’re meant to really fear, that’s a big cultural myth that perpetuates this idea that prisons are natural, normal and necessary. I know there’s a book where the guy had spent time in Broadmoor as a psychiatrist working with five of the top serial killers in the UK. He said not a single one of them hadn’t had the most brutal, traumatic childhood.

So for me in terms of actually dealing with people that have perpetuated that level of harm, I think it needs to look more like a care model. I used to work with autistic adults, for example, that were quite violent and aggressive and it would be about what meets their needs. So I could imagine smaller systems where we actually treat individuals as needing care and support rather than needing more violence inflicted upon them.

Could you say a bit about where the permaculture comes in? Some people would think permaculture and prisons just means making gardens in prisons, but I get a sense from your work that you see it as a much deeper thing than just planting a few apple trees in the yard in the prison.

For sure. For me, permaculture and prisons have always been quite linked. I learnt about permaculture inside – I got a Distance Learning course when I was in prison and studied permaculture in there, worked in the gardens and encouraged the garden officer to let us grow veg rather than just weeding rose bushes. I’ve always seen that they do go together quite well in the sense that I see permaculture as being a way to completely redesign our society that meets human needs while increasing ecosystem health.

I get a lot of emails from people that want to do projects with prisons and plant gardens, but this isn’t really the work that I’m doing, or the work that I’m overly interested in. Being in the gardens in jail really kept me sane and really nourished me while I was there, but it’s a very cosmetic intervention. I feel that the power of permaculture gives us a lot more ability to transform society than we imagine at the moment.

So for me, it’s more about totally redesigning our societies from the ground up, which is obviously what people engaged with the Transition movement are doing and that’s super inspiring.

But I’m not dismissive of projects with prisoners. There are some really inspiring examples, especially in North America. People leaving prison really need support. They really need access to create a new way of life, because most people coming out of jail are landing straight in the same situation: poverty, benefits, drugs, violence, the same sort of patriarchal culture. So creating opportunities for prisoners to come out of jail and actually access land and build livelihoods, to find purpose and meaning, and actually be able to feed themselves, would be super inspiring and necessary.

I’ve met people who have been in and out of prison who actually will often get sent back to prison because it’s some stability. It’s regular meals, you’re warm, and I wonder what does that tell us about how crap stuff is once you get out and how little support there is when you get out, that going in and out and in and out just becomes a pattern for people. How do we break that pattern?

Without a doubt. Something like 65% of offenders – I don’t like the word offender – but of prisoners return within 6 or 12 months. So most people in prison are people that have been there before. There’s a design tool in permaculture, this idea of “a spiral of erosion”, identifying where that erosion is happening and where the leaks are. I feel like we can intervene in that system by looking at why people are returning to prison.

Without a doubt. Something like 65% of offenders – I don’t like the word offender – but of prisoners return within 6 or 12 months. So most people in prison are people that have been there before. There’s a design tool in permaculture, this idea of “a spiral of erosion”, identifying where that erosion is happening and where the leaks are. I feel like we can intervene in that system by looking at why people are returning to prison.

The main reason is getting kicked out of jail with a £46 discharge grant hasn’t changed in the last 4 years. Then you have to wait a month maybe to get your benefits sorted, and the grants from the state like the emergency fund from the Job Centre aren’t available any more. The Salvation Army is completely over-subscribed. You can’t get on the housing register and it’s literally no surprise that people return to prison. No surprise at all.

I could really see the change in the just-under 2 years that I was there, with all the government austerity measures, and how that was really harming people because all the services inside the prison were just getting stripped left, right and centre. The housing team lost their jobs, the group that worked with foreign national women lost their funding and then people were getting out and were completely unable to access support from charities or other bodies that used to exist. So prisons really link with this national impact of the state, and it’s basically class war on working class people in the UK.

Could you paint us a picture of what your vision would be of a fair, just, justice system? If you were to leap forward 20 years and this had happened, could you paint a picture of it for us? What might it be like?

For me, fairness is actual real social justice and a real egalitarian society, and I don’t feel that’s possible in our economic system and I don’t feel that’s possible when we have the existence of the state which is going to protect the people at the top of the hierarchy. So to have fairness would be to totally transform all our social relations and make our society less stratified and less hierarchical. Ideally, in my fantasy head, an anarchist society where we’re addressing our power relationships left, right and centre, where the minority don’t have a monopoly on violence over the majority.

In terms of a more positive, creative vision – it would be communities actually being less atomised and having relationships with each other, and people actually paying attention to things like sexism, racism, so that there aren’t such endemic levels of domestic violence or drug abuse. Most substance abuse comes from people being sexually abused when they were kids so if we actually had a revolutionarily different society that kind of harm hopefully wouldn’t happen, or at least in definitely wouldn’t happen at the levels that we have now.

So I can imagine a constellation of alternatives in communities developing different tools and when we don’t have the haves and the have-nots I’m sure that would definitely stop a lot of the crime as we know it happening.

How might we start to move towards what you’re talking about? We’re so far away from it at the moment.

We need to be investing time and energy into developing ways to respond to harm. Things like Transformative Justice are a lot more common in the US, but we need to really build up those tools and those ways of existing so that we can actually meet our own needs without the state. So I feel like that’s something that if people are interested in People Care or Zone 00 work or Inner Transition, then they could be actually really addressing some of the different forms of oppression that we have in our society like racism, sexism, able-ism and even just thinking about things like class within the Transition movement and the permaculture movement.

To me these feel like huge elephants in the room that we don’t discuss enough, so really looking at design interventions around them. Practical projects with ex-prisoners, I think is super important. If every permaculture project or community garden in the UK could support a couple of apprentice ex-prisoners, I think we’d definitely make some sort of dent.

But more than anything, it’s this idea of “are we making gardens in this battlefield?” I do feel like we need to politically engage with this and if people are really passionate about permaculture then applying design to grassroots campaigns. They’re building Europe’s second biggest prison right now in North Wales. Six days ago they announced a new prison they want to build in Jamaica funded by the British state. These are all things that are happening right now and I don’t feel like we can be neutral and I don’t feel like we can be passive. We need to organise and we need to resist the growth of the expansion of the prison system while simultaneously developing alternatives and doing more one-to-one work with ex-prisoners.

More information on Nicole’s work linking these issues here. She also suggested, for those interested in learning more, the following links:

Empty Cages Collective resources section

Community Action on Prison Expansion

Bristol Anarchist Black Cross

Critical Resistance (North America)

Read more»

5 Oct 2015

Lay out the map of Hannover and the first thing that strikes you is the amount of green space in the city. About 25% of the city is green space, it includes a forest, and it is home to 20,000 ‘Kleingärten’ (small gardens), which are larger than allotments, and managed by associations. It also has a number of waterways running through it. I was visiting Hannover to speak at two different conferences, happening simultaneously, on opposite sides of the road from each other.

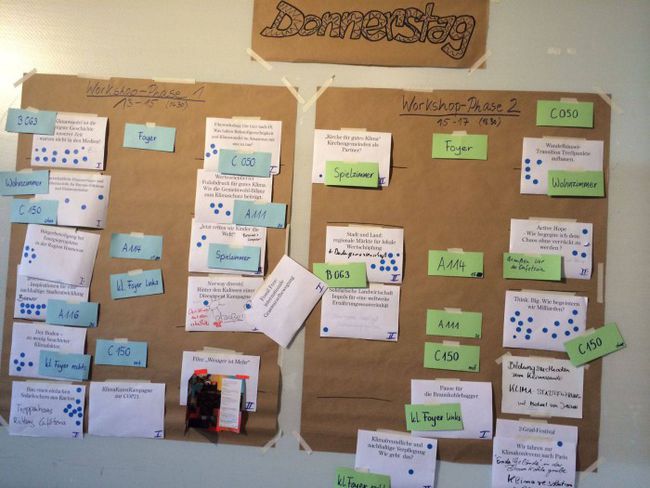

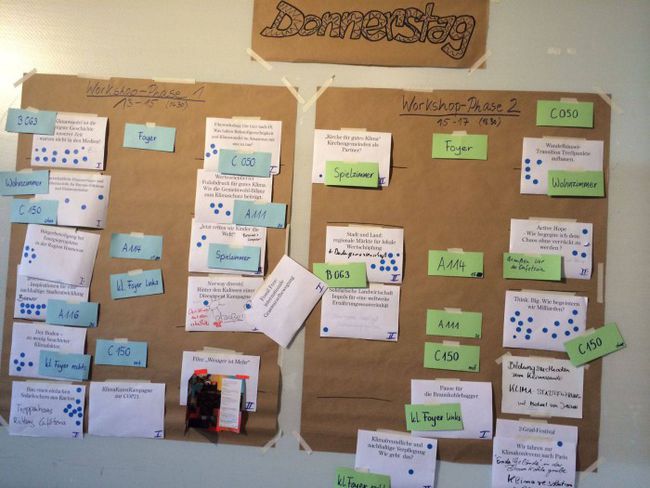

The first was the UnKonferenz, organised by Transition Town Hannover. It was a climate change conference that featured lots of workshops, Open Space, and room for things to just self-organise. The whole thing was run on virtually no money, and was really rather lovely. I sat in on a rather interesting Fishbowl thing, in which members of Transition groups from across Germany talked about what they were doing.

The Unkonferenz was a new and important development in the evolution of Transition in Germany because climate protection is mostly a field addressed by other, much larger NGOs. Also, the Unkonferenz brough together a wide diversity of organisations, activitsts, associations and NGOs from across the spectrum of bottom-up group in a space that enabled sharing, exchange and listening. It was also an event where the first steps were taken towards holding the first Local Entrepreneur Forum in Germany next year.

Later that evening, I gave a presentation, presenting some of our forthcoming ’21 Transition Stories’, as well as having a conversation with Maaret Westphely, a Green Party member of the regional government. The evening ended over the road in the other conference, with an amazing modern take on an oompah band … here’s a short taste of what I enjoyed before I headed off to bed.

The next day was all based on the other side of the road, at ICCA2015, the Internationale Kommunale Klimakonferenz. This was an event focused on the role of “local governments driving transformation”, and was part of Germany’s formal build up to COP21 in Paris in December. I was part of a “high level panel” along with Stefan Wenzel, Minister for the Environment for Lower Saxony, Prof. Martin zur Nedden, Research and Managing Director at the German Institute for Urban Affairs, Dr Barbara Hendricks, the German Minister of the Environment, Henri Djombo, Environment Minister of the Republic of Congo, and Dr Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, Director of the Potsdam Institute. Dr. Hendricks and Mr Djombo gave keynote speeches and then Dr Schellnhuber gave short overviews of our perspective before we moved into a more general discussion about the role of citizens, communities and local government in the run up to Paris in December.

Then there was a Fishbowl event, run in the ‘Climate Neighbourhood’ fringe section of the ICCA event, again with Dr Hendricks and others, including some local school children, which was very interesting.

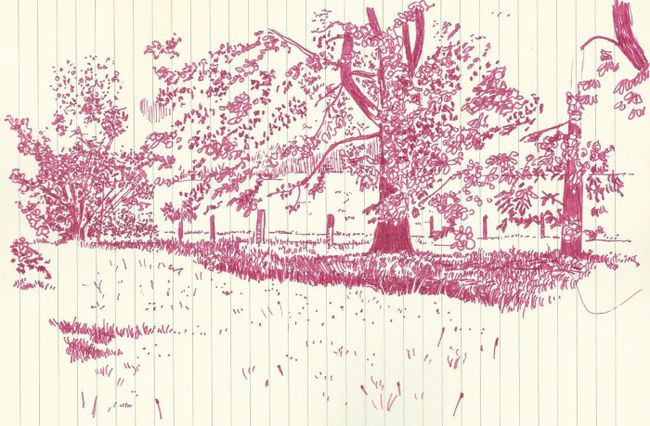

I then had some time off for an hour and a half, and so, given the amazing weather, I went off into the park, sat under a tree, in the sunshine, and did some drawing. Here’s my picture:

The last part of the day was a tour of some of the projects that have emerged due to the work of Transition Hannover on board an amazing old 1970s retro bus.

The first place was the work of Transition Hannover North, a project called Egons, “Haus der Möglichkeiten”, which translates as the “House of Possibilities”. The group have taken on one of the city’s larger ‘Kleingarten‘, one which included a small building which they are renovating. The house serves as a base for meetings and events, and the garden is being converted into a food garden, a process that requires bringing in soil as the soil onsite is so bad. The group have regular work days, and also manage a nearby plot of apple trees.

Due to time running low, we had to skip one project, which is a gardening project working with refugees, and go straight to ‘Palagalino’, a community garden set up by the Transition group in the Linden part of the city. The name Palagalino comes from “Pala” (the garden is built using pallets), “Ga” (a shortening of “Garden”), “Li” (short for “Linden”, the part of the city”) and “No” (short for “North”, as they are in the north of the city).

The garden is a community garden serving a large community, and it features many raised beds, which are managed by different people. Some of the beds were being run as experiments using terra preta (biochar) soils. It was a gorgeous oasis in the city, thriving with the kind of diversity and creativity that is often found in community gardens.

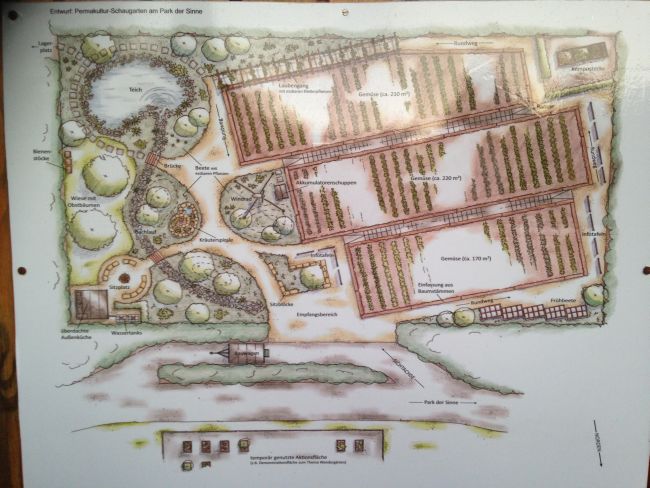

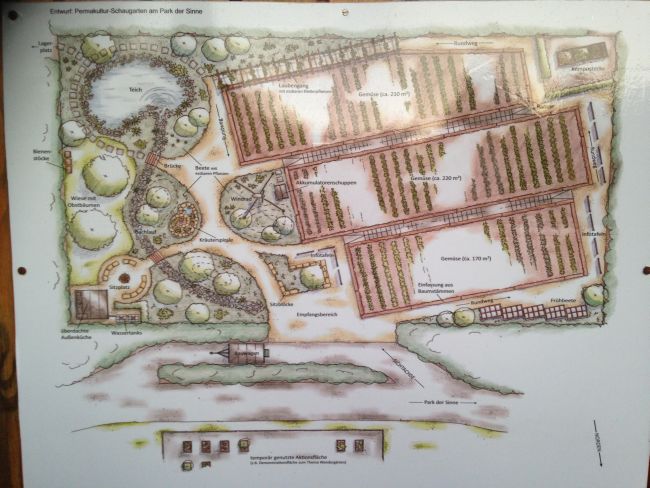

Our last stop was Mitmachgarten (which translates as the “Participatory Garden”), the most ambitious of the projects we visited. It is sited on the edge of the city, next of an area of large sports pitches, and a visitors attraction called the ‘Senses Garden’, which was created for the city’s Expo in 2000. The challenge here, rather than the somewhat more chaotic and homespun nature of the previous two gardens, was to create something smart and landscaped enough that it would inspire confidence in the site’s organisers that Transition Hannover could expand and take over more of the park.

The garden was in two parts. The first, along the route of a jogging track around the park, was designed as a perennial edible rest stop, planted with blueberries and other fruits so as to act as a kind of natural and healthy pick-your-own pitstop. The main garden has been created by a team of unemployed adults as well as a paid core staff. It was a beautiful space, designed both for food production (some of what they grow goes to a local restaurant) and for wildlife. The garden is designed to maximise biodiversity, with a pond, and all sorts of habitats for different creatures. It is also designed so as to create habitats for several different kinds of bees, featuring a rather fine Bee Hotel.

It appears that in Hannover, the bulk of the efforts of Transition groups goes into food growing projects, although this isn’t the case everywhere in Germany. It felt really useful to be able to act as one of several bridges between the two conferences, to be able to fly the Transition flag (it’s very nice, you should see it) in the high level panel. Thomas, one of the co-ordinators of Transition Hannover said “your visit has helped us to take things here to another level”, which was good to hear. After such a warm welcome, and meeting so many great people, it’ll be interesting to hear how things develop going forward.

Thanks to everyone of Transition Hannover, Dr Thomas Köhler, Stephanie Ristig-Bresser, Anja and Kai, my hosts, everyone at Adelphi, who invited me to speak at ICCA, Gerd Wessling for joining me on the train, and all the wonderful people I met.

Read more»

5 Oct 2015

It’s a question many people are asking, and it’s one that was discussed at the Transition Network conference a couple of weeks ago. While there is no definitive answer, and the response will look different in each place, I thought you might be inspired to hear the story I recently heard when I visited Brussels. I visited members of 1000 Bruxelles en Transition to see their amazing Potager Alhambra, of which more next month. While I was there, one of the group, Julien Bernard, told me the amazing story of a spontaneous refugee camp that many of the Transitioners were central in initiating. Although not formally a 1000 Bruxelles en Transition project, it captures beautifully one example of what a response to the migrant crisis might look like if underpinned by Transition thinking. Here’s the conversation we had, standing in the Potager (it is transcribed below if you’d prefer to read it).

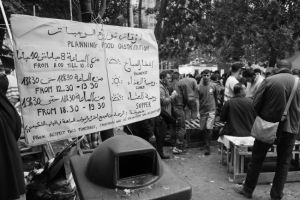

“Me and other citizens were some of the first to get mobilised for the refugee camp. From the end of August the number of refugees coming into Brussels became much larger and they needed to go to this government building to register and request asylum. The government policy is that they process a certain number of people per day, and they didn’t increase capacity for processing when the number of refugees started becoming larger. People saw themselves forced to stay in this park which is just in front of this government building while waiting for their turn to be processed.

The first days were pretty chaotic because there was nothing prepared to receive anyone. The refugees slept in the park, but there were no tents, there was nothing prepared. The first citizens came in to give them soup, and people quickly mobilised to provide a wider range of support. So in the first few days we had piles of food in one corner and donations in another.

Gradually the help started getting more structured and different groups of people came to take care of different tasks. After the first week there were 200 people in the camp and 100 volunteers. 20 days later there was this big general assembly with about 1000 people, refugees and volunteers, to try and create a more structured support. After that assembly meeting, we created different working groups with different tasks and it became a lot more organised.

Each working group started working more or less autonomously while keeping the other groups informed about what they were doing. After a while there were about 1000 refugees in the camp. There was also a huge mobilisation of people everywhere, not the volunteers in the camp but people who gave donations. After a few weeks there were tons of donations of food and clothes and tents and materials. The volunteers built a huge kitchen that serves 3 meals to 1000 people every day and there was a non-government organisation that came in also to help with medical care.

The camp is managed by these volunteers day and night and this citizen mobilisation was done in spite of our government, it wasn’t very reactive and didn’t do much to receive refugees. Due to this citizen mobilisation, the government was finally pressured into opening up a few spots to receive refugees through this transition period while they are waiting to be processed. There are still not enough of those places, so there are still people staying in the camp, but it was still a big political shift.

That political shift, what did that look like? Presumably, it went from a place where the government was saying no, no, no. How did this action start to change government thinking?

One of the main things was that the action was prolonged in time so we didn’t get weaker and people didn’t go away. The problem was still visible. Also that the whole presence of the volunteers was done in the spirit of positive communication of seeking solutions and the movement remained non-partisan, non-political. Last time there was a gigantic citizens’ march, not a protest, but just a march of solidarity with the refugees, where about 25,000 people took part.

Could you say a bit about the role of Transition Bruxelles?

This is not a project from the Brussels Transition Group, but several people from the Transition Group took part from the beginning. A lot of people who came to help are part of organisations who share this view of positive solutions and action.

I think the thing that made this refugee camp work was that we applied ourselves to it with the same mentality that we do the Transition projects. We had a positive mindset, we focused on getting concrete results, and looked for concrete solutions. Everyone took pleasure in seeing how it evolved and seeing it work and it gave everyone a feeling that they could actually change things and make it work.

Everything in the camp was built using recovered and reused materials, so there was absolutely no budget. The group doesn’t even have a bank account, so it was just donations and reused materials. The other thing that happened is that this served as an opportunity for many people to become active citizens, whereas in other situations we tend to be quite passive. There was a mental click that showed people that they can be active and they can have an influence. This ended up mobilising thousands of people who might have had that mental click and might be using it.

Here is a film from Al Jazeera about it:

How is your Transition group responding? Do you have a story to share? Please use the comments box below.

Read more»

29 Sep 2015

I was recently travelling to Ungersheim in France to give a talk, a journey that involved passing through several train stations. On the journey I had been reading Michael Shuman’s fantastic new book ‘The Local Economy Solution‘ (highly recommended). In it, he paints a rigorous and passionate case for economic localisation, and in particular what he calls “pollinator” enterprises.

A pollinator enterprise is self-financing, and its role is to weave the local economy back together again, to bring about a different local economic model than the current one of throwing open local markets to big companies, focusing instead on growing the local sector. In many ways it’s a model that sounds like what REconomy is doing, that combination of Local Economic Blueprints, Local Entrepreneur Forums, business mentoring and support, crowdfunding, local currencies and so on. It certainly feels very affirmingly familiar, so far, but I’m only on page 57 so I don’t know where he may yet take it.

I arrived at Paris Gare de l’Est with Shuman’s ideas going round and round in my head, and feeling like I quite fancied, in the 50 minutes before my train, sitting down and having a cup of tea. Gare de l’Est is a big station, but while there were several places you could grab a panini and eat it standing up (all chains so far as I could see), there were only two places where you could actually sit down and have a drink. One was a very large Starbucks, whose seating area took up a meaningful chunk of the concourse. The other was much smaller. And it was also a Starbucks. Two Starbucks, one large, one small, within a stroppily-hurled coffee cup’s distance of each other. That was it.

I’ve written before about the potentially powerful role that train stations could play as pollinators. With so many people passing through them, they have huge potential to incubate new enterprises, to showcase local food, local dishes, local entrepreneurs. Clearly someone in the management at Gare de l’Est has taken the decision that Starbucks can pay the most rent so let them have the space. But what if they had taken a different approach and had several smaller outlets? If in unused space at the station they had created a La Cocina-style incubator for new food businesses, and featured them on the station? What if stations (and now we’re on the subject, other public spaces like schools and hospitals) were required, when deciding how to lease their space, to maximise social return, a cultural return, the Multiplier Effect, and also a public health return? How might that nudge their thinking, and what we might end up with instead?

It was recently reported that WH Smith had been found out for charging up to 90% more for goods sold in their shops situated in hospitals than on the High Street, outrageous practice I grant you. A survey in Leeds, for example, found them to be charging £1.89 for a 750ml bottle of water in the hospital, but just £1 in a city centre shop. But in all the coverage no-one asked why it was that in many hospitals your self-catering choices are a WH Smith and a Costa, neither renowned for their commitments to local produce or especially healthy fare, both extractive industries. Hospitals as pollinators? Is that really such a leap from their current public health remit?

In that previous blog, I mentioned the rather fine craft brewery bar on Sheffield station, and I recently visited the new Kings Cross station and was impressed by the number of small, independent food businesses. The station at Crystal Palace station features a great independent cafe serving local produce. There are undoubtedly more. But the general trend is for them all to be the same dull names: Pret; Costa; Starbucks; Pumpkin; Scoff; Trough; Yawn; Bore (OK, I may have made a few of those up, but you get the point). Gare de l’Est sits in a part of Paris with a high immigrant community, many of whom are trying to gain an economic foothold in the city, to start their own businesses. Paris is a city of great food, of regional dishes, of urban agriculture pioneers, and of a rich tapestry of different cultures and their distinct cuisines. It’s a city that historically sat at the centre of complex, largely localised food webs. But arrive at Gare de l’Est station and you’d be none the wiser that that was the case.

At the recent International Permaculture Conference I heard again and again the old permaculture maxim that ‘the Problem is the Solution’. Never are the words more apt than in thinking about Gare de l’Est station. The solution to some of the problems faced in the area, and the role the station could play in addressing them, is blindingly obvious (to me at least).

In the Transition future world of 2025, I imagine walking into Gare de l’Est, and being greeted by delicious food smells. Walking down the concourse, I am spoilt for choice. There is a wide variety of beautifully presented food, made with mostly local ingredients but with recipes from around the world. My attention is drawn to the Food Entrepreneurs’ School in rooms above the station, training local young people in a range of food-based skills. The station owners have themselves invested in many of the best entrepreneurs who have come through the School. It’s a station where bread is baked, beer is brewed, falafels are fried, naans are stuffed and spices are ground.

And then take that and spread it out across the world, station by station. How much more fascinating, rich and delicious would travel become? How much more vibrant would each local economy become? We would be so proud of our stations. They would be how we would show off to visitors how much more interesting we are than we used to be. Pollinator stations, your time has come. But not the airports, we hopefully won’t be needing them much by then. They’ll have been turned into great urban farms: Terminal One Fungi, Terminal 3 Carp and so on. To quote, as I often do, Elliot Murphy from his sleeve notes for ‘1969: Velvet Underground live’, “I wish it were a hundred years from today (I can’t stand the suspense).”

Read more»

28 Sep 2015

I am often asked the question what it might look like if a local government really took Transition by the horns, initiated it, and acted as the catalyst for the community to start a meaningful and impactful Transition process. Having visited Ungersheim in the Alsace region of eastern France, I can now tell you exactly what it looks like.

I was invited by Ungersheim’s remarkable Mayor, Jean-Claude Mensch and the Comune d’Ungersheim to speak at their ‘Les rencontres de la Transition’ event (“meetings of Transition”) and to see what they have been doing there. Several years ago, Mensch hosted a visit by an organisation called the General Assembly of the Citizens of the World, at which the film ‘In Transition 1.0’ was screened. It led to a conversation in the Comune along the lines of “we’re already doing that, let’s become a Transition town”. And so they did.

They are the first Transition initiative I know of to be launched by a local authority in this way. Ungersheim is a village with a population of around 2,000, and is a place with a long history of mining. At its peak, the extraction of potasse, used to make potassium for agricultural use and to made sodium chloride (salt) for treating ice on roads, employed 13,000 people in the region. The last mine closed in 2003. In France, Mayors have a lot more power than they do in other parts of the world, so it is fascinating to see just what can be achieved when a Mayor is inspired by Transition. Here are some of the things that have already been done in Ungersheim. The village has:

They are the first Transition initiative I know of to be launched by a local authority in this way. Ungersheim is a village with a population of around 2,000, and is a place with a long history of mining. At its peak, the extraction of potasse, used to make potassium for agricultural use and to made sodium chloride (salt) for treating ice on roads, employed 13,000 people in the region. The last mine closed in 2003. In France, Mayors have a lot more power than they do in other parts of the world, so it is fascinating to see just what can be achieved when a Mayor is inspired by Transition. Here are some of the things that have already been done in Ungersheim. The village has:

- Introduced more participative democracy

- Become a Fair Trade town

- Formed a citizens forum about renewable energy and campaigned for the closure of the Fessenheim nuclear power station

- Launched a local currency, ‘Le Radis’ (the radish)

- Mapped the biodiversity of the area in an ‘Atlas of Biodiversity’

- Returned a former waste heap created by mining to nature

- Installed a 120m2 solar thermal installation at the swimming pool

- Installed a wood biomass boiler which also heats the pool and several adjoining buildings

- Built Helio Parc 68 (of which more later), a 5.3MW solar installation and industrial estate

- Changed all the public lighting in the village to low energy bulbs, leading to a 40% reduction in energy use, as well as turning some street lights off after midnight

- Assessed all public buildings for their energy consumption

- Made land available (land owned by the Comune) to a PassivHaus co-housing project, Eco-Hameau Le Champré (of which more below)

- Completely banned all pesticides and herbicides in public areas

- Replaced all cleaning products in public buildings with eco cleaning products

- Bought a working horse to help with local food production, and also to act as a ‘bus’ to take local school kids to school

- Changed the catering arrangements so that the local primary school now serves 100% organic meals, every day, including snacks

- Transformed 8 hectares of land owned by the Comune into an organic market, Les Jardins de Cocagne, which produce 64 varieties of vegetables, provide 250 baskets of food for local families each week, and which run stalls at 5 markets every week

- Started a food preservation business, canning locally produced food so as to extend its availability

It’s a story that has attracted national and international attention, indeed while I was there, the film-maker Marie-Monique Robin was filming for a documentary about Ungersheim, due out next year. I also heard of at least 6 new Transition initiatives that have formed in towns and villages around Ungersheim, inspired by what is happening there. It’s quite something.

Our day started at the Mayor’s office in the centre of the village with about 30 people. We saw a film introducing the work underway there, and heard a short welcome from Mr Mensch. Here it is, it gives a great overview (in French though, of course):

Over a shared organic and Fair Trade breakfast we talked and people asked questions. Then we were into a horse-powered carriage, and off to visit a fantastic co-housing project. The Comune had made the land available at a realistic price on the understanding that the houses that were built would be PassivHaus buildings.

The resultant co-housing project is built using local timber, and will be home to 9 families. Each family have created their own process, finding their own balance between professional builders and self-built. Houses are south-facing, timber-framed, made with ModCell-type pre-manufactured strawbale panels, with a communal solar hot water scheme and shared gardens. Insulation is with straw, wood fibre boards, blown cellulose and one I hadn’t seen before, “wood wool”.

We saw round some of the houses under construction and met some of the residents, as well as the architect, who described it as his “dream project”. Then we were into the horse-drawn carriage and back to the centre of town, to a large marquee that had been erected in the centre of the town, for a communal lunch.

Our next trip was to the official opening of Helio Parc 68, a 5.3MW solar farm. The site was a former waste site associated with the mining, which had been cleared and levelled and transformed into what will become a business park, with the thousands of solar panels, the biggest single solar installation in the Alsace, mounted on structures that could, as some already have, been fitted out as industrial units.

A large crowd had gathered, including local dignitaries. Having never inaugurated anything in my life before, this was the first of three inaugurations that day! Along with someone representing the developers, we unfurled a banner launching the scheme, and then I switched on one part of the installation. Remarkably ambitious, and of a scale that I’ve not personally seen before. Here’s a piece that appeared in the following day’s regional newspaper:

Our next stop, and my second inauguration, was at Les Jardins de Cocagne, an 8 hectare market garden which acts as a training and support resource for unemployed young people. Here, for weeks before, a team including local school children had been building a wind turbine with wooden blades, inspired by the work of Hugh Piggott. Again, a large crowd had gathered, and after a short speech from the Mayor, I flicked the switch to allow the turbine to be hydraulically lifted into place, to much applause and cheering. Once it had all been bolted in place, it began to spin, much to everyone’s delight.

We also looked round an absolutely gorgeous new complex of buildings that will become a place for the market garden to process its produce, to store it in a new underground cool room, to can and preserve produce as well as to have its office. We looked round with the architect. An absolutely gorgeous structure that I would move into tomorrow at the drop of a hat, it featured a local timber frame, wooden shingles on the roof (always a treat for the eyes), strawbale infill and it will be finished with a clay and straw daub coat. The complex of buildings are created around a circular courtyard, what will be an absolutely delightful space. I can’t wait to see it finished.

We then looked around the very impressive farm, with dozens of huge polytunnels and wide range of produce. The farm supplies the now-organic primary school among other things, a great example of what they call “short circuit”, shortening the distance between grower and consumer.

We then headed back to the centre of town for Inauguration Number Three. For what was called ‘La Semaine Solaire’ (‘Solar Week’), at the Mayor’s invitation, a Greenpeace group from Switzerland had been working with a group of teenagers from the local Lycée, mapping every roof in the town, analysing elevations, size and so on, concluding that if every roof that could take solar PV were to do so, they would meet 77% of the town’s energy needs.

It was a project that had had a huge impact not just on the young people involved, but also on the Greenpeace activists. Most of their work has been around saying no to things, campaigning and resisting, and this shift into taking positive and practical steps was something that had touched them deeply.

The local school was launching its new 40Kw rooftop solar PV installation, and it was the opportunity to also recognise the young people who had been part of the project, giving them each a certificate, before I formally unveiled the installation’s meter showing its output and generation. They also gave me one of their ‘La Semaine Solaire’ tshirts, on which they had written, “Pour Rob, on behalf of Lycée Théorore Deck, the first Lycée en Transition in France”.

After a short break, featuring local organic beer and a traditional kind of oompah folk band, I gave my evening presentation. Before I spoke, some students from the local primary school came on stage to announce that they were reimagining their school as a School in Transition, and shared with the audience what they were doing, which included recycling, growing food, and having someone in each class whose role it is to turn the lights off each day.

With the help of the wonderful Peter, who had been my translator all day, I gave an overview of Transition and why what is happening in Ungersheim is so important. So many people came, that the 20 minutes before I started saw a constant putting out of new chairs. We had a great Q&A session and then everyone milled around the many stalls of great local initiatives, and headed out again to the marquee for supper, wine and conversation.

One of the most powerful things about Transition I think and one of the reasons it has spread so far and wide, is the principle we borrowed from Open Space of “Let It Go Where It Wants To Go”. By trusting people, giving resources and tools away for free, with the only ask that Transition groups share their stories and experiences, a culture has been infused that trusts innovation. Like many areas of Transition, the edge between Transition and local government is just that, an edge. Can we say that Transition should never be initiated by a Mayor or local government? It clearly takes a pretty remarkable person to do it, but in Jean-Claude Mensch we have that. I’ve seen a few failed attempts in the past, but the proof of this particular pudding is in the eating.

One of the most powerful things about Transition I think and one of the reasons it has spread so far and wide, is the principle we borrowed from Open Space of “Let It Go Where It Wants To Go”. By trusting people, giving resources and tools away for free, with the only ask that Transition groups share their stories and experiences, a culture has been infused that trusts innovation. Like many areas of Transition, the edge between Transition and local government is just that, an edge. Can we say that Transition should never be initiated by a Mayor or local government? It clearly takes a pretty remarkable person to do it, but in Jean-Claude Mensch we have that. I’ve seen a few failed attempts in the past, but the proof of this particular pudding is in the eating.

What’s more important is that within the French context, Transition appears to be springing up all over the place. I was told that there are now 60 local currency schemes already in operation in France, with good coordination ensuring that they are all good neighbours to each other. The Transition mycelium is live and running. In this context, being able to point to Ungersheim, where the Mayor and the Comune are making so much amazing stuff happen is very powerful. The story of how the Mayor of Bristol takes his full salary in Bristol Pounds is a story I tell in all my talks, and it always generates a reaction of “wow, this stuff is stepping up and being recognised”. Ungersheim represents the next level of that story. It was an incredible thing to see, and I am very grateful to have been asked.

My thanks to Jean-Claude Mensch, to the Comune of Ungersheim, to my host Phillipe and my translator Peter, to Transition France, to Amber and to all the wonderful people I met there.

Read more»

As a design, the prison system is incredibly effective in the sense of who it’s serving. It’s serving the State, and it’s also serving the hierarchies that exist in our society. Anyone who is engaged in any sort of social change work will probably see prison or repression as a limiting factor or a fear to overcome to push for more change. Prisons are fundamental to maintaining this social order in our society and they’re really essential to maintaining this class-based system that we have, especially in the UK.

As a design, the prison system is incredibly effective in the sense of who it’s serving. It’s serving the State, and it’s also serving the hierarchies that exist in our society. Anyone who is engaged in any sort of social change work will probably see prison or repression as a limiting factor or a fear to overcome to push for more change. Prisons are fundamental to maintaining this social order in our society and they’re really essential to maintaining this class-based system that we have, especially in the UK. A lot of those tools already exist, especially in more anarchist subcultures. We have things like ‘safe spaces agreements’ and accountability processes. There’s a model that has come out of North America called ‘Transformative Justice’ which emerged due to the needs of survivors of sexual violence wanting to not endanger the perpetrators of that violence and subject them to the criminal justice system but actually to look at alternatives and to support them to transform their behaviour, so everyone is transformed by that process; it’s not just a case of restorative justice where you’re restoring the same power imbalances that perpetuate the harm.

A lot of those tools already exist, especially in more anarchist subcultures. We have things like ‘safe spaces agreements’ and accountability processes. There’s a model that has come out of North America called ‘Transformative Justice’ which emerged due to the needs of survivors of sexual violence wanting to not endanger the perpetrators of that violence and subject them to the criminal justice system but actually to look at alternatives and to support them to transform their behaviour, so everyone is transformed by that process; it’s not just a case of restorative justice where you’re restoring the same power imbalances that perpetuate the harm. Without a doubt. Something like 65% of offenders – I don’t like the word offender – but of prisoners return within 6 or 12 months. So most people in prison are people that have been there before. There’s a design tool in permaculture, this idea of “a spiral of erosion”, identifying where that erosion is happening and where the leaks are. I feel like we can intervene in that system by looking at why people are returning to prison.

Without a doubt. Something like 65% of offenders – I don’t like the word offender – but of prisoners return within 6 or 12 months. So most people in prison are people that have been there before. There’s a design tool in permaculture, this idea of “a spiral of erosion”, identifying where that erosion is happening and where the leaks are. I feel like we can intervene in that system by looking at why people are returning to prison.