10 Nov 2015

Last week we introduced a piece of work we have been doing at Transition Network called ‘The Transition Story’, which is also our theme for November and December. In a blog entitled ‘The Transition Story: time to stop talking about climate change?‘, I gave a brief overview of the basic idea and the new suggested story flow. The article has generated some fascinating comment, both here, and over at Resilience.org. Today we want to share with you a video of the workshop Sarah McAdam and myself presented at the 2015 Transition Network International Conference, which goes into the discussion in more depth and which includes the questions and debate it generated. Our thanks to Mike Thomas for producing this video.

Read more»

3 Nov 2015

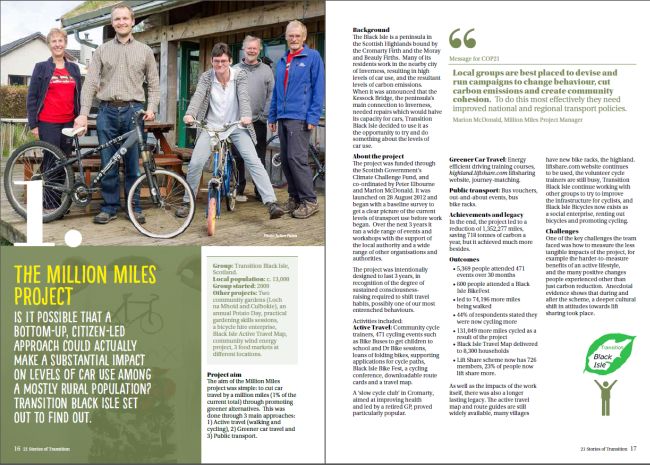

Yesterday we gathered with Totnes Mayor Jacqi Hodgson to formally launch our new book ’21 Stories of Transition’. Our last publication, ‘The Power of Just Doing Stuff’ was launched into the River Dart two years ago with the previous Totnes Mayor in a boat fashioned from a pumpkin. We did also ‘launch’ that book into the sea from Worthing Beach in a specially-made boat, but it kept coming back. This time we wanted to take the notion of a ‘launch’ in a different way, as is captured in this video of the sombre and moving occasion.

You can order your copy and also keep up with the 21 Stories here. ’21 Stories of Transition’ is now shipping. Here’s the first batch heading out the door…

Read more»

2 Nov 2015

Today we launch a theme exploring ‘the Transition Story’, our opportunity to unveil work we’ve been busy with over the last 12 months or so. The thought I want to seed in your brain today is whether a more skilful way to inspire a response to climate change, and a more skilful way to achieve all the things we want to achieve in the Transition movement, is to spend less time talking about the issues that drive why we do what we want to do, the problems, that challenges. Like climate change. Stay with me.

One of the things that has been generating a lot of thinking in recent months at Transition Network has been the idea of “frames”. In his seminal book “Don’t Think of an Elephant”, George Lakoff defines frames as:

“…mental structures that shape the way we see the world. As a result, they shape the goals we seek, the plans we make, the way we act, and what counts as a good or bad outcome of our actions”.

The Transition Story: from ‘response’ to ‘movement’

We’ve been exploring what might be the frames for Transition, through a fascinating piece of work with Jon Alexander of the New Citizenship Project which we call ‘The Transition Story’. It looks at how to tell the story of what Transition is about, at what are the most effective frames to use. It has been deeply insightful.

Alexander argues that Transition has come to the end of what he calls its ‘Response’ frame (which has run through all our materials to date back since the start of Transition – you know, “Transition is a response to peak oil, climate change, economic crisis, etc. etc.”) and would find it more effective to focus on a ‘Movement’ frame. He writes:

“We believe the opportunity is to start from where people NOW are, with a shared but hazy sense of how unsustainable the dominant global culture is, and which most of us are suppressing and holding at arm’s length because it is just too big to allow into our daily lives – rather than where people WERE when Transition started, which was arguably unaware. The task is to stand side-by-side with people and ask questions with them, not in front of us with a confrontation we have already decided to run away from”.

It’s a rich insight, one I have been digesting for the last few weeks. He encapsulates it thus. For him, Transition would benefit from redefining itself as “a movement of communities coming together to reimagine and rebuild our world”. At the moment, the flow of how we present Transition tends to run like this:

There are some huge problems out there

But don’t panic

We can respond

Here’s how you can be part of it

The Transition Story project shifts that, suggesting that instead the story we tell now flows like this:

A movement is building

Here are the things all the different people are doing in their communities

It’s rooted in caring for ourselves, each other and the living world

This shows a different future is possible when we come together

(Optional: This is why it’s needed)

Here’s how you can be part of it

It’s worth sitting with for a while and allowing to settle in. It certainly has led to lots of rearranging of grey matter for me over the past while. It’s a shift that Sarah McAdam and myself presented at a workshop at the 2015 Transition Network International Conference, a video of which we’ll be posting here soon.

Over recent weeks I have given a number of talks, such as this one at the International Permaculture Conference, where I have presented, and embodied, this idea that we don’t need to always start talking about Transition with a long list of reasons and graphs that show the disastrous state of the world. We start by saying that we do Transition because it’s bloody fantastic, and it changes peoples’ lives, and it meets our needs far better than the current economic model does. That’s enough.

As Cheryl Lyon of Transition Town Peterborough puts it in ’21 Stories of Transition’, “we don’t want the catastrophe to do the work for us”. When I start talks in this way, it invariably generates a round of applause. We have so much to celebrate, so let’s celebrate it.

But do most people “know there needs to be change”?

Alexander’s observation resonated with something Sarah Woods said at the end of the interview I did with her that we published a couple of months back:

“All the people who are not, for whatever reason, motivated by climate change: they’re good people, they care, they’re people who do good things in their lives, but for whatever reason they are not affected deeply by these ideas of change. Most people know there needs to be change. In the work that I do, whether I’m asking about people’s car use or people’s relationship to food or energy or climate change or the weather, everybody knows.

People know, but that doesn’t mean they can act. Our job is not to go out and tell people what we think, but to start from what people think and what people deeply know, and then find ways to connect that back to a bigger shared story. The truths are out there almost in the furthest places from us”.

“Most people know there needs to be change”. This very much resonates with what Jon Alexander wrote:

“We live in a time – and this is pretty global – when there is a broad if suppressed recognition that things cannot go on as they are. In this context, starting by pointing that out is more an unnecessary confrontation than a useful convening point”.

But is he right? Is there really a “broad but suppressed recognition that things can’t go on as they are?” It’s a risky assumption. For example, might it be that many of those voting for UKIP in the recent UK election (some of whom we know are also active in Transition initiatives) are also driven by a deep sense that things can’t go on as they are, yet the amount of fear-based rhetoric they encounter daily in the media leaves them with a sense that a fear-based response is the most appropriate one? Discuss.

Is it time to talk less about climate change?

It’s a counter-intuitive question perhaps, but a vital one. Transition suggests a different frame, one based in compassion, honesty and trust. If we are able to voice that skilfully, who’s to say it won’t reach those currently dazzled in the glare of those more fear-based frames? Alexander’s proposed move from ‘Response’ to ‘Movement’ is key to this I think, and for me represents a momentous and historic shift in how we frame Transition, certainly one that underpinned how we created ‘21 Stories of Transition‘, and how it tells its story.

By now, most people who are drawn to the issues to which Transition is a response are already on board, or at least know about it. But there are many people who would be attracted to much that Transition does, to many of its initiatives, but are put off by the associations that accompany climate change and other issues, as well as the ‘alternative culture’ associations that sometimes accompany some Transition groups.

People may care deeply about their community, its history, its young people, its ecology, its transport issues, the quality of the food available, the Clone Town nature of its High Street, the impacts of austerity cuts on local care services and so on, as well as about larger global issues, but not be driven by a concern about climate change or about the finite nature of many of our key resources. So how to invite them to the party?

It’s already happening

This shift in how we talk about Transition is already happening in many Transition groups I talk to. Quite a few are already starting to move away from always framing their work as a ‘response’. The South Wales Evening Post reported on a recent event which launched Transition Neath. It quoted one of the founders, Emma Knight, as saying “this event is about starting a community conversation about the long-term future. It is about the community taking responsibility and doing something for itself. It’s a negativity free-zone – we will be focused on what can be done rather than what can’t”.

The Independents for Frome group, a group of independents who are revolutionising local government in Frome, several of whom have roots in Transition in the town, is another great example of their being able to be more effective by seeking the common ground. Here’s their fantastic video from the recent election which gives you a good sense of what they’re all about:

For a growing number of people in Transition there is a sense that we can be more impactful, have a greater relevance and reach, if we don’t put agreeing to climate change and the various other drivers as an entry requirement, the “unnecessary confrontation” Alexander mentioned. This is something again that comes through very strongly in the 21 Stories we will be unveiling this month.

So next time you talk to someone about Transition, or write something about it, or give a talk, just try it out. Try losing the “what Transition is in response to” framing from the front of your talk, and just start with what you love about it, the impacts it is having, how a movement is building. Tell stories, allow your passion for the changes you have seen it making to your life, to your community, to the wider world. Those issues that you are responding to will inevitably come through in your stories. Try it out, and see how it works for you and let us know. We’d love to hear your thoughts on this article, and on our ongoing deepening into the subject over the next 2 months.

Read more»

29 Oct 2015

On Monday we launch our new book ’21 Stories of Transition’ and today we begin our build up to COP21 in Paris which starts at the end of the month. Often our default setting as people who are motivated by climate change is to lobby, demonstrate and campaign to try to bring pressure to bear on those decision makers to make the best deal possible. And yes, of course that stuff matters, and there’s a lot of it ramping up for COP. But in many ways, the world is already changing, and it’s happening at pace, it’s fast and it’s deep. Are we expecting COP21 to be that moment of fireworks and dancing elephants, a ‘Great Change Moment’, when people dance in the street and subsequently put plaques up to immortalise the moment for their grandchildren? If we are, we’re missing the point.

The Great Change? We’re in the middle of it.

If you believe things aren’t changing, you’re looking in the wrong place. More and more forms of renewable energy, such as onshore wind, are now the cheapest form of electricity in many places. Even the CEO of Shell, Ben van Beurden, now says “in the years to come, solar will be the dominant backbone of our energy system”. Towns and cities around the world are taking the lead, far outstripping their national governments’ carbon reduction targets. The Bank of England, among others, are now warning of ‘stranded assets’ as a result of the ‘carbon bubble’ with Governor Mark Carney warning that losses could be “potentially huge”. Prince Charles recently told a meeting of fossil fuel investors if they wanted to be remembered as “future makers or future takers”. The divestment movement is growing fast, a trend you want to be the first to act on, not the last.

Coal is finished. The US coal industry has lost 76% of its value in the last 5 years. The oil industry is increasingly aware that the writing is on the wall, BP for example recently acknowledging that due to concerns about climate change, it is unlikely now that fossil fuel reserves will ever be fully exploited. Shell recently abandoned drilling in the Arctic, “for the foreseeable future” because it found so little oil. Support in the UK for onshore wind continues to grow, with a new government survey finding that 74% of people saying they’d be happy to have wind turbines near them, and only 24% being happy to have fracking, with women, interestingly, far more likely to be opposed to it. China aims to quadruple the amount of solar it has installed by 2020.

The Pope has spoken out on climate change in a way unimaginable a few years ago, framing climate change as a moral issue, as has the Islamic Declaration on Climate Change, and the Dalai Lama. Even the G20 leaders have talked for the first time of “phasing out fossil fuels”. Even if their proposed deadline, 2100, is actually 70 years too late, it is still important that the language of the end of fossil fuels is now out there and running through our culture.

COP21 is acting as the catalyst for many organisations, businesses and governments to refocus on climate change, move finance into climate change, put pressure on governments to create a stable environment within which to build a low carbon economy. All manner of shifts and realignments are going on behind the scenes. And the politics are changing to accommodate this new worldview, for example I was inspired recently by this piece about the Global Network of Rebel Cities. Then there’s the rise of Podemos and other movements, and the incredible laboratory for new approaches that Latin America is becoming. The ousting of the Harper government in Canada also gives COP21 increased possibilities.

Telling our stories

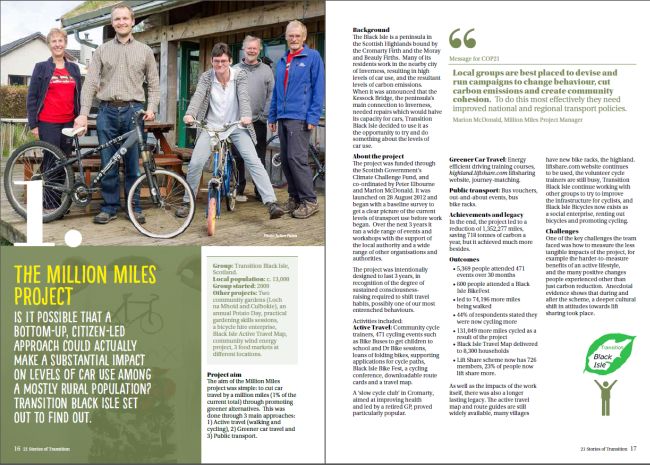

On Monday, we at Transition Network are publishing a new book called ’21 Stories of Transition’, our contribution to the talks in Paris, which tells, in English or in French, stories from 39 Transition initiatives in 15 countries. When put together, just those 21 stories have, among other things:

- generated 18,527 hours of volunteer input (and that’s just from the handful that measured this)

- Put over £1 million of complementary currencies into circulation

- Created 43 new social enterprises

- Reduced car travel equivalent to driving to the Moon and back 3 times

- Saved 7,450 tonnes of CO2 just through renewable energy installed (enough to power 4,000 homes)

- Begun work on building projects with a value of £5,150,371

- Raised over £13,155,104.88 for investment in renewable energy

- Produced enough boxes of vegetables to feed 550 families a week

And these are just the measurable ones. What of the relationships built, the degree to which people feel more hopeful, skilled, connected, positive, resilient? What are the gardens actually growing? What are the community energy companies actually generating? What are the construction projects actually building? And these are just a fraction of the thousands of Transition groups in now over 50 countries. And these are just a fraction of the wider, diverse, and innovative networks of grassroots responses happening around the world.

This can no longer be dismissed as “a few do-gooders making community gardens” (as Transition was once rather patronisingly described to me). This movement of bottom-up approaches, whether it’s called Transition or not, is happening everywhere, and it’s moving mountains.

I remember COP15 in Copenhagen. I didn’t go, but the sense of crushing disappointment it created took the climate change movement many years to recover from. What so many of us were expecting and desperately hoping for was a Great Change Moment, when world leaders and corporations would realise that they had made the most appalling mess of everything, would then embrace with great gusto the opportunity of creating a more resilient, low carbon, sustainable future and remodel capitalism accordingly. With hindsight, that was a somewhat unrealistic expectation.

When it didn’t happen it felt dark and desperate, like the greatest dereliction of duty imaginable. With COP21 just over 4 weeks away, might it be that a longing for a Great Change Moment means that we are psyching ourselves up for another bout of crushing disappointment?

But those Great Change Moments rarely ever happen, and if they do, they are desperately few and far between. People are already writing off COP21 in Paris as a waste of time. It is increasingly clear that it won’t result in an agreement that will limit the world’s emissions to less than 2 degrees, which is, after all, the point. So it’s a waste of time then? I don’t think so.

How change actually happens

Change happens in interesting ways. For example, recently, a community campaign where I live challenged a large local charitable landowner’s land use decisions, in particular its decision to submit large swathes of land for development. The community campaign questioned the link between the organisation’s stated values and its actions. Looking back in hindsight, it’s interesting to see how the change unfolded, and how there is no one single Great Change Moment to point to. But at the moment when the then CEO of the organisation was brazening it out, telling everyone how the organisation was listening and responding when it was clear that he really wasn’t, actually the ground had been eaten away from under him, and it was empty words, and a month later he had stood down. Events were moving, the world around him was changing, he had been left behind.

Similarly the GDR, East Germany, looked to be robust, powerful and permanent in the days before the Berlin Wall came down. In reality, we now know, it was holed below the waterline, undermined by the number of young people defecting to the West, corruption, rigged elections and much more. But until the Wall came down, you’d never have known. So how can we know, in the moment, which point in time we might point to as the moment when the change actually happened?

What Transition brings to COP21

While Paris looks likely to not be that Great Change Moment, perhaps it is we who need to take a different approach here. Our role in Paris, or during that time, in my opinion, is not to see this event as a Great Change Moment, rather as just yet another important step in the ongoing – and of course massively urgent – building of a new, low carbon world. Instead, we should focus, during that time, on celebrating what is already happening. And there is much to celebrate.

The stories of change outlined above tell us far more about what is already moving than what is thrashed out in a vast, soulless, air-conditioned conference centre. And those trends are growing, building, regardless of what is decided. Rather than give our power away, surrendering the degree to which we believe a low carbon world is possible to the wording of an agreement made between leaders, we need to take it back, to state clearly, loudly and often that it is they who risk being left behind here.

Like the local campaign with the landowner I mentioned earlier, what is agreed at COP21 is just a moment in a longer process, a snapshot of a rapidly flowing stream. What is happening beneath the surface, the currents that are set, the infectious nature of ideas, the human disinclination to be left behind and seen as being out of touch, the way that tipping points work, are all really the great unknowns here. And as ’21 Stories of Transition’ shows, we have so much more power in this than we might think we have.

Last year we spoke to Andy Lipkis of Tree People in Los Angeles. He told us:

“Our job is to make viable the alternative and have it ready. If we’ve really done our homework, we could scale this thing in a flash”.

It is to building that viable alternative that I put my shoulder. It is celebrating that viable alternative that will be the focus of my time in Paris in December. I was recently in Hannover, and spoke, along with Germany’s Environment Minister, at an event that was that region’s ‘On the Road to COP21’ event. It was fascinating to see how, in those discussions, Transition, and other approaches to bottom-up organising, were a missing piece of the puzzle. They had no idea how to mobilise communities, indeed they recognised that they weren’t the people to do it.

COP21 as a historic opportunity

For many years now the fossil fuel industry, and associated industries, have collaborated strategically, using their wealth and power to do everything they can to make sure that we go on emitting carbon. They’ve been helped in this by the growth delusion, and the connection between economic growth and using energy. If we’re going to succeed in moving to a low carbon, resilient and sustainable way of living in the time we have to make a difference, we’ll have to be just as strategic as those who want to go on with the status quo. That means seizing opportunities – and COP21 is a significant opportunity to tell the stories that so need to be heard. That’s a story of possibility, and economies designed to of increase wellbeing both right now and for our children’s children’s children. There is a win/win/win/win economy to be built here.

Rather than retreating into the cynical view that COP21 is a waste of everyone’s time, I would suggest that we see it rather as the opportunity to appreciate and to celebrate a transition that is inevitable, that’s already happening and, to quote the late David Fleming, “has the decisive argument in its favour that there will be no alternative”.

At COP21 I’ll be marching in the Transition Bloc in the Solutions section of the Peoples Climate March on November 29th. I’ll be speaking at whatever events I can to tell some of our 21 Stories, and inviting other people to share theirs. I’ll be doing whatever I can to share this stuff. We will soon be sharing a calendar of events that will be happening in the city if you want to get involved. And I won’t be putting any energy at all into there being a Great Change Moment. What happens is what happens, but something brilliant and historic is already underway, and our message to the Obamas, Camerons and Merkels of this world needs to be that it’s already happening without them, and they need to support and enable it, but even if they do nothing, it will continue to grow, because it’s the future.

’21 Stories of Transition’ can be ordered here. You’ll be glad you did. It has already been described as “the most attractive, simple and accessible output yet that I have seen about Transition”.

Read more»

27 Oct 2015

In our final post on our theme of fairness, we talk to Julie Brown. Julie is Director of Growing Communities, a social enterprise based in Hackney in North East London. They run a box scheme which supplies vegetables to about 1000 households in Hackney and run the weekly Stoke Newington Farmers’ Market. They also do urban food growing on what we call a ‘Patchwork Farm’ on small sites in Hackney and a larger site in Dagenham. The other thing they do is run a startup programme, working with other communities to help them set up similar projects. We started by asking Julie what, for her, does a fair food system look like? What are its elements, its criteria?

“It is quite hard to separate the concept of a fair system from a sustainable one, so I’m going to muddle them together. In overall terms, what a fair system would do is to pay farmers who are farming in a sustainable way, it would pay them a fair price so that they could actually survive and thrive.

In big terms, that’s probably one of the fundamental unfairnesses about the food system as it currently is. The farmers that are attempting to do the right thing for the planet and for diets and for other elements that we want to have fantastic food, these are the ones that find it almost impossible to make a living and survive in the current system. There’s some sort of really fundamental unfairness there. That’s probably where I would start.

A fair food system would also produce food that is good for people, and affordable, and accessible to everyone. It would be fair to workers. It would pay people in retail outlets and agricultural workers as well as people running businesses a fair price, and it would be fair to communities, so communities would have a say in how things are run, they would be connected to the farming and the people that are producing their food, and the businesses that were running in their communities wouldn’t be extracting value from those communities.

They’d be investing back into those communities, and it would be fair to the planet, so it wouldn’t be degrading soil, reducing biodiversity and causing climate chaos.

Why, for you, does bringing food closer to home make it fairer? A big focus of your work is around reconnecting food production to place…

There’s a number of different elements to that as well. There’s the food miles type element of it but that’s only a very minor part of it really. It’s the fact that food that is produced closer to where it’s eaten tends to be fresher and involve less resource problems in terms of its transportation and production.

But it’s also about transparency and connection. I think you care and are able to relate better to things when you know where they’ve come from, and you know who has grown them. That relationship is going to be more fair and more respectful because it’s more transparent and it’s clearer. You can’t guarantee that obviously, but that’s what tends to come out of that.

So again, if I relate it to very practically how we work, we care about our farmers. We know who they are. We want to them to do well. We want them to be able to run their business and carry on producing the fantastic food that they do. And we want to be able to provide it to the people that come to the market and who buy food through the box scheme at a fair price. So if we look at the elements that are linked more directly to money, what we try to do through our projects again is make sure we start with the price that we pay the farmer, that we pay them the price that they need to farm sustainably. That’s the thing that is currently going in entirely the opposite direction to that at the moment in terms of the way the food system is heading now

Maximising productivity is defined by getting maximum yield for the least amount of money, or involving the least amount of labour. All the other external costs of the food system: the soil degradation; the climate impact; the impact on wildlife; none of those are costed in. The way we define what is “good” about farming systems works entirely against producing food in a sustainable and fair way. Farmers who are attempting to not work in that way are being driven out of business by that world view. That direction of travel, essentially.

What we’re trying to do at Growing Communities is trying to reach out directly as communities to those farmers and saying “we’ll buy your food at a fair price”. So we start with that. Then we try and work out how we’re going to pay people in Hackney through the box scheme and the farmers’ markets so that they can actually work on those projects.

We have a commitment to paying people the London Living Wage, and we have a 2 to 1 pay structure, so nobody is paid more than twice the lowest paid worker in our organisation. Then we are looking at how we can sell the food to our customers at the most affordable price. That’s the sort of equation that we’re working with, that’s the financial equation we’re working with.

But we start with that basic, fundamental principle that we have to pay the price that’s required to have food produced in a way that doesn’t have all of these negative impacts and actually brings amazingly positive impacts. Through that, reconnecting with the farmers and also creating enterprises locally, we can create community, which is another thing in our name which is a bit of a hint. So we can create community, we can create jobs and the third element is in terms of our organisational structure, which again is what’s not fair about the current food system.

We say we are “driven by principles, not by profit”, so we’re a not-for-profit. We want to cover our costs and we want to make a surplus, but we want to reinvest that back into our projects and into our community. It’s about investing in community, not extracting from community.

We talked before we started about this Eco Modernist thing that was recently launched (Eco Modernist statement here, and George Monbiot’s brilliant demolition of it here). They would argue that surely the bigger and bigger scale you produce food on then actually you can put more land just down to wild systems and you can produce food cheaper and so you have more biodiversity and cheaper food, and isn’t that a fairer system?

Er, no. That’s the short answer.

The long answer? There are so many 1+1=5 sort of issues going on in that. We have to, I believe, accept that there are limits. There are biological and natural limits to what we need to be doing on the planet to live sustainably. Now I’d argue, to go back to those Eco Modernists, I don’t think they’ve quite accepted that, that there are limits.

I’m really happy to be applying science and technology and creativity to the issues around food and farming and, in fact, of everything. But we need to do that within a framework that accepts that there are natural limits. There are climate limits, there are soil limits, there are water limits. People are going to argue about yields, it comes back to this yields/productivity discussion again.

But if we looked at the food and farming system through a different productivity lens, one that looked at labour actually as a positive output of the system, not a cost, and actually properly costed the energy resources and the other resources that were required to produce food, then the smaller-scale systems would actually look much more favourable. I’m not going to say they’re going to blow the other ones out of the water, but I think in some cases they would.

We think the foundations of a sustainable and fair food and farming system are small to medium scale enterprises. We’re not talking about one size fits all either. I talk about it in terms of ‘food subsidiarity’. We’re talking about an appropriate scale and multi-scaled operations depending on the food that’s being produced and whether it’s mainly arable or livestock or horticulture, although there is a real value in all those types of systems getting more mixed.

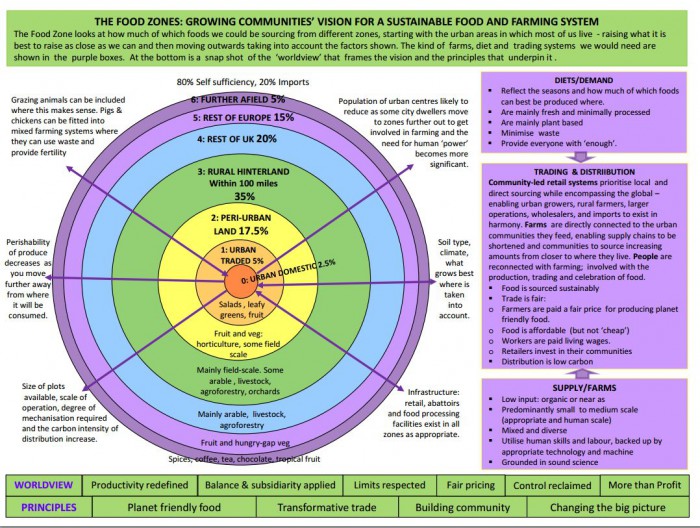

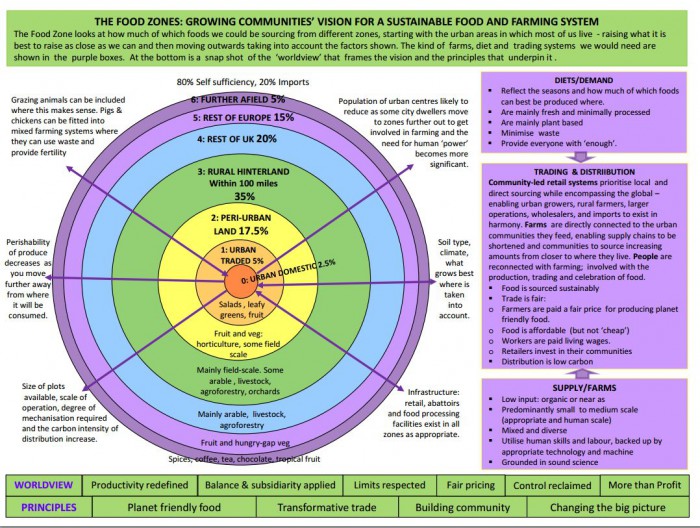

We would support a mixed farming system. We also need to look at the supply side as well as what diets are like and what people are expecting to eat. It’s hugely complex, in terms of livestock production and how much food people should be eating of different types. Our latest Food Zones map looks at the kind of farming systems we think are the basis of it, essentially multi-scale but mixed farming systems – low input, pretty much organic, and utilising human skills and labour, and it’s backed up by science and technology and machinery, but it’s grounded by sound science.

That sound science is about observing and seeing what’s going on in quite a complex system, which farming is, but we’ve got to look at the demand side as well, which is that we need to be eating a mainly plant-based diet, and mainly fresh food, reducing the amount of processed food, minimising waste. All of those things are going to produce a diet that is really pretty good for you. But we need to pay farmers to farm in that way.

You mentioned your Food Zones map. I sometimes show that in talks and people find it really fascinating in terms of the degree to which you’ve thought through the implications and the practicalities of London sitting in the middle of that kind of a food web. I wonder if you could just give us a sense of where that came from and what you think its key implications are?

It has come from many years of working in this area, pulling all the different elements together into what is essentially a vision of how we would like to see the food and farming system operating. It’s also totally based on the very pragmatic way that we work. The percentages are roughly based on what we managed to do through our box scheme.

Our box scheme is trading just fruit and veg, so in terms of the wider food system, some of that is still to be proven. But actually I’m working on a project at the moment which is going to attempt to model this and see what diet would be produced if we actually did operate like this. The way that I’d like to do it again is through a very practical approach, which is to find the best example which is currently in each of the zones and then to multiply it up into the zone in terms of the amount of land that’s in theory available, and then what sort of food and the quantities it would produce.

But then I’ll have to change the percentages because that’s what you do anyway. It’s based on an intuitive knowledge of all the different factors, throwing them all around together into this thing. I would eventually like to prove it, but I think we’ll prove it by doing it. We are actually doing it, because when this Food Zones was first produced, there were little, tiny pockets of things going on and now there’s masses of stuff going on. Lots of new people are getting into farming and actually into retailing and into CSA schemes, urban production and lots of amazing new activity going on, which it would be great to track it and show it more clearly, but also show what the impacts of it are more clearly, and show that it actually is starting to create a real alternative to the mainstream food system at the moment.

When I show it in talks, I sometimes say that to me it’s like a map of the new economy. If I was 18 now, and looking at that, I’d be thinking – I want to train to become a really good market gardener, a craft brewer or a mushroom grower or something. It presents so many options and possibilities to people, that’s what I love about it.

Thank you. I noticed a talk when you said that. We need to prove it now! We need to prove it by doing it as well. That’s the thing, Growing Communities’ approach has always been about an empirical and theoretical approach. There’s this overall vision and we very practically just go out and create stuff that’s actually going to be real.

Read more»