Archive for “Originally posted on Transition Network” category

Showing results 71 - 75 of 383 for the category: Originally posted on Transition Network.

29 Nov 2015

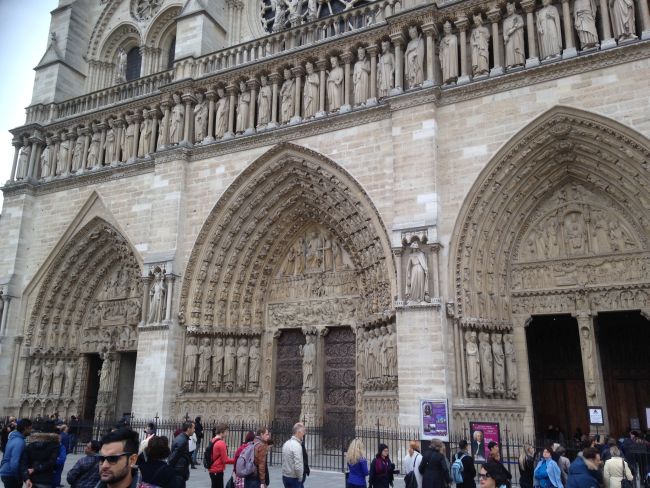

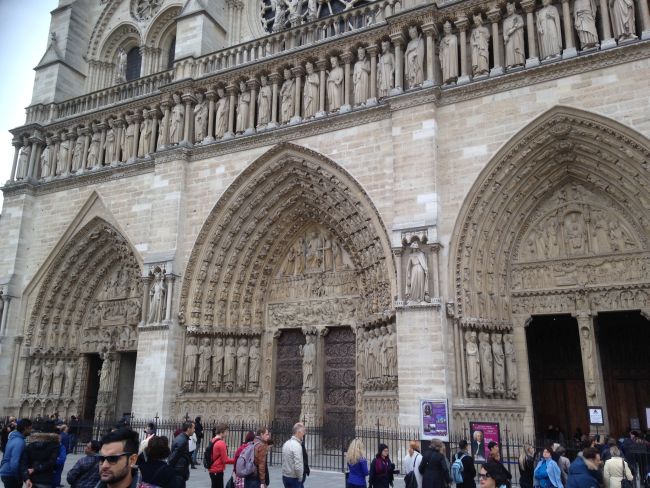

This will be a brief report given that it’s late and I need to get some sleep! Emilio Mula (filmmaker) and I, after a very early bleary start from Totnes, arrived in Paris around 3pm to be met by some Paris Transitioners, who, among other things, told us about the climate activists in Paris who had had their apartment raided by hundreds of police and then put under house arrest. Felt like we were arriving in the middle of very interesting times. We were then whisked off on a crowded bus to La Generale, home of the afternoon’s events.

The bus took us part the Bataclan, home of the worst shootings during the 13/11 terrorist incident, currently a kind of shrine, with flowers, candles and so many people coming to pay their respects that the bus struggled to get past. On the other side of the road were similar shrines, and flags and pictures on the fences. The now ubiquitous Eiffel Tower/peace symbol was repeated in many places, hard to square alongside President Hollande’s assertion that the response to the attacks will be a “war” that will be “merciless” rather than, in the build up to the Iraq War, France taking a moral stance about peacemaking, showing restraint and leadership.

Seeing the shrines though made the events of a couple of weeks ago much more real, and it is clear that these next two weeks in Paris will be, at least in the conversations that take place around COP21, focused not just on climate change, but on that other ‘unintended consequence’ of the Oil Age, terrorism. It is certainly in the minds of many people I talk to, as citizens make the connection between oil dependency, the deeply dubious political allegiances we have to make in order to continue that dependency, the seeming lack of will to address root causes of conflict but rather to just plough on generating more, and the climate crisis. It’s not rocket science. I doubt those debates will take place at COP21 itself, but they are certainly taking place on the streets around it.

La Generale is a large space, a former postal sorting place currently, in the remaining year before it is demolished, in use for music and as an arts space. Things had been happening during the day there, Open Space, food, conversation and the like. When I arrived I had to dash off to a quiet room to do a Skype to the launch, in Arles, of a new book by Lionel Astruc, called Le pouvior d’agir ensemble, ici et maintainent, a book based on a series of interviews with me. About 200 people were squeezed into a hall in Arles and I gave them a short, virtual, overview of Transition. I had really wanted to go to Arles, being a Van Gogh nerd and all, but timings didn’t work out sadly.

After the Skype was the main evening occasion. About 200 people gathered to help us launch the French edition of ’21 Stories of Transition’, and after getting people to map where they come from, I shared some of the stories. Some of the stories were told by other people, for example, Julien and Marie from 1000 Bruxelles told the story about the Potager Alhambra in Brussels, and Jean-Claude Mensch, the Mayor of Ungersheim, told his story.

After the talk, I got people into pairs to chew over what they felt to be the key threads running through the stories, which led to some very interesting reflections. Then, after a couple of questions, the evening drew to a close, followed by much milling, book signing, debating and chatting. A very fitting launch for the new book. Deepest thanks to all the Transition France guys for pulling the evening together. Lastly (because it’s the wrong way round and would take up too much space) here’s a picture of me speaking at the event taken by Henry Owen.

Read more»

24 Nov 2015

I am one of the people who made it to the end of watching the series ‘Lost’. I really quite enjoyed it in places, but in the end it got bogged down in its own silliness, with plot lines that went nowhere and the promise that the whole thing would eventually make sense (which it never did), and when the whole thing finished with the most contrived, ridiculous and utterly unbelievable ending, I came to rather resent the 3 days and 18 hours of my life that I had invested in it. Getting to the end of Leigh Phillips’ book ‘Austerity Ecology and the Collapse Porn Addicts’ was a similar experience.

This is a book that would have you believe that “the back-to-the-land ideology and aesthetic of locally-woven organic carrot-pants, pathogen-encrusted compost toilets and civilisational collapse is hegemonic”. Phillips wears his antagonism on his sleeve throughout, referring to Transition folk, degrowthers and the wide spectrum of the Green/alternative economics world as “anti-packaging jihadis”, “degrowth militants”, “green Mr Magoos”, and “an army of tattooed-and-bearded, twelve-dollar-farmers’-market-marmalade-smearing, kale-bothering, latter-day Lady Bracknells”. Plaudits for creative writing aside, hopefully you are getting a sense of where Phillips is coming from. This is a tirade which starts out attempting to sound rational and informed, but which as the book goes on, loses the plot entirely.

‘Austerity Ecology’ is published by Zero Books, who imagine themselves as holding some kind of line against ‘cretinous anti-intellectualism’, and publishers of Greg Sharzer’s atrocious hit job on localisation ‘No Local’, a book so bad I didn’t make it beyond the third chapter due to his basically making the same point over and over again, basically “localisation is a rubbish idea because Marx said so”. ‘Austerity Ecology’ tries really hard to avoid doing the same, but in the end just can’t quite help itself.

Phillips’ central thesis is that he sees the rise of those on the left who question economic growth and consumer culture, and he is appalled. “Far from being central to progressive thought”, he writes, “this cauldron of seething, effervescing misanthropy is in fact utterly alien to the rich tradition of humanism on the left and must be thoroughly excised from our ranks”.

He argues that we need growth, and more of it, and to argue otherwise is anti-progress, anti-modernist, even anti-human. “There will need to be more growth, more progress, more industry, and, above all, we will need to become more civilised, if we are to solve the global biocrisis … this new paradigm of rejecting growth and embracing limits is also by definition a rejection of progress”, he fulminates.

All of which leads us to an interesting discussion about what exactly progress is. “The logical conclusion of degrowth is ineluctable”, he writes, “we must remain technologically, scientifically, medically frozen. All new innovation linked to the material world must be relinquished”. What rubbish. Phillips sees progress as being about inventions, about things, machines, devices, economic growth.

New Economic Foundation recently published their suggested five headline indicators for national success in the UK. They argue that the 5 measures should be Good Jobs, Wellbeing, Environment, Fairness and Health. They seem like pretty good indicators of “progress” to me. Surely progress should be that the places where we live feel like they have more control over their own future, more options, better connected, increased biodiversity. That people are becoming healthier, wiser, more fulfilled. When the Caring Town Totnes initiative asked local people “what makes you unwell?”, the answers were not about disease, but about loneliness, isolation, stress, financial worries. When government fails to address those challenges, then it falls to us as communities to do so. To take such a narrow definition of ‘progress’ really does nobody any favours.

I recently visited Ungersheim in north eastern France, where the Mayor has taken to Transition with huge enthusiasm, and, among other things, has:

- Introduced more participative democracy

- Become a Fair Trade town

- Launched a local currency, ‘Le Radis’ (the radish)

- Mapped the biodiversity of the area in an ‘Atlas of Biodiversity’

- Returned a former waste heap created by mining to nature

- Installed a 120m2 solar thermal installation at the swimming pool

- Installed a wood biomass boiler which also heats the pool and several adjoining buildings

- Built a 5.3MW solar installation and industrial estate

- Changed all the public lighting in the village to low energy bulbs, leading to a 40% reduction in energy use, as well as turning some street lights off after midnight

- Assessed all public buildings for their energy consumption

- Made land available (land owned by the Comune) to a PassivHaus co-housing project, Eco-Hameau Le Champré

- Bought a working horse to help with local food production, and also to act as a ‘bus’ to take local school kids to school

- Changed the catering arrangements so that the local primary school now serves 100% organic meals, every day, including snacks

- Transformed 8 hectares of land owned by the Comune into an organic market, Les Jardins de Cocagne, which produce 64 varieties of vegetables, provide 250 baskets of food for local families each week, and which run stalls at 5 markets every week (and provides the food for the schools)

- Started a food preservation business, canning locally produced food so as to extend its availability

It certainly felt like progress to me and to everyone I spoke to there. People were really excited about the changes they could see happening around them. It did not feel less civilised, less human.

Phillips would have you believe that Transition/Degrowth/anti-consumerism thinking has taken over the world, that he is alone in holding out against this tide of babbling unreason. Like UKIP railing against the dominance of “political correctness”, he would have you believe that localisation and post-growth ideas and the idea of limits are ideas “that … dominate in contemporary culture”. Really? “Anti-consumerism has become a fundamental doctrine of the modern left, indeed of mainstream thought across the board” he rails. Really? Apparently, “the idea of a balance of nature is … deeply embedded in our culture”. I think we must be living on different planets.

Have we seen any political parties in this country, even fringe ones, running on policies around economic contraction and localisation? Even the Green Party was talking up growth during the last election. How often do these ideas even appear in the mainstream media? On television? On the radio? In discussions in most pubs up and down the country, or on the football terraces?

What are the actual trends we see happening in the world? The relentless erosion of local economies and independent businesses. The ongoing destruction of small farming. Vast crossborder organisations like Amazon destroying bookshops and other retailers while avoiding the tax arrangements other businesses are bound to.

And how about the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), being negotiated in private between governments and corporations, which would make intentional localisation virtually illegal? In spite of this book not having an index (never a good sign – I thought Zero were a bastion of intellectualism?) I searched through it for mention of TTIP, but it didn’t appear once, leaving the impression that Phillips believes the localisation movement is a greater threat to social justice and fairness than TTIP.

If I were to address all the ludicrous arguments in this book this review would be almost as long as the book it is reviewing, so I have picked just a few of the key turkeys. The first arises from his use of the term ‘Austerity Ecology’? He argues that:

“One cannot in one breath rage against the imposition of economic austerity – the series of radical cuts to social programmes and depression of wages imposed by most Western governments in the wake of the global economic crisis – while arguing against economic growth. Austerity and ‘degrowth’ are mathematically and socially identical. They are the same thing. What green degrowth partisans are actually calling for is eco-austerity”.

This is just one place in the book where Phillips parts company with reality (although not a patch on what comes later in the book as you will see). It is a ludicrous point. The kind of austerity suggested by Transition, post-growthers and the like is profoundly different from that being imposed by George Osborne and his ilk. Osborne’s version imposes negative distribution of money, resources and services, whereas the other version advocates for a positive redistribution.

Under Osborne’s austerity, the rich get richer, the poor get poorer; in a degrowth/post-growth approach the opposite happens. Under a degrowth/post-growth scenario, no-one starves to death, no-one freezes to death in their homes. In the UK we are now back to levels of inequality not seen since the Edwardian times, and Osborne’s austerity measures only add to that, the opposite of the degrowth approach. Degrowth has social justice, fairness, the idea of a ‘Maximum Wage’ designed into it, the opposite of Osborne’s approach. Clearly they are completely different, not “socially identical”. To argue otherwise is completely disingenuous. And, given the publisher’s commitment to intellectual rigour, no evidence is presented at all for his argument that these two versions of austerity are “socially identical”. No mention, for example, of Peter Victor and Tim Jackson’s work attempting to model what ‘ecological austerity’ might actually look like in practice. No mention of Tradeable Energy Quotas, David Fleming’s brilliant model for reducing carbon emissions while also building social equity.

Secondly, he argues that local currencies actually increase carbon emissions, “for the simple reason that the sort of larger loads in your car when you travel to the non-local-currency-accepting big box retailer can mean fewer trips there”. I’ll leave you to reflect on the stupidity of that particular argument.

“Improving the wealth of a community requires economic development, something at which the Transitioners look askance” he adds. Keep up Leigh. Have you seen the Economic Blueprints some Transition groups are developing? The REconomy Project? The millions of pound of inward investment being generated by community energy projects? The shift in Transition to creating new local economies, new local businesses, to communities owning their own assets, becoming their own development? Local Entrepreneur Forums? We refuse to comply to the straw man you are creating for us.

Thirdly, he argues that localising food production, growing food closer to where people live:

“…means turning more forest, wetlands and grasslands into agricultural space, releasing vast quantities of carbon in the immediate term and, in the future, eliminating the carbon sinks that forests would have represented”.

What utter nonsense. Look at the local food projects being started by Transition groups and others around the world. Take Crystal Palace Transition Town’s ‘Patchwork Farm’, growing food across Crystal Palace in parks, gardens, school grounds, unloved corners. Or Liege en Transition’s Ceinture d’Aliment-terre project, reconnecting the city to the land around it as a learning network of farms serving local needs. Or Growing Communities in Hackney and their Food Zones model for feeding London. Or the research by the Urban Design Lab that showed that New York contains 1,200 acres of potential rooftop growing space.

No forest clearance, no wetland draining. No huge releases of carbon. Rather a bringing back to life of urban land currently covered in rubbish, or using food growing as a way to breathe life into public spaces, to reimagine peri-urban land currently home to stockbrokers’ daughters’ ponies, to bring food security, employment, beauty and wellbeing to disenfranchised urban communities. No swamp draining required. Sounds like progress to me.

Transition gets its very own kicking, in a wildly inaccurate ranty sort of “and your mum smells” kind of way. He refers to “the locally-woven organic carrot-pants (it’s those carrot pants again) and peak -oil millenarianism of the Transition Town movement”. On the day I read his accusation that:

“the whole Transition worldview promotes an austere politics-of-limits mindset that retards human flourishing”

… we took delivery of the new Transition Network publication ’21 Stories of Transition’. A vibrant, colourful collection of stories from 39 Transition groups in 15 countries, awesome in the diversity of what they’re doing, and the real impacts they’re having. Stories that have, between them:

- inspired 18,527 hours of volunteer input

- put £1,032,051 worth of complementary currency into circulation

- created 43 new social enterprises

- Raised over £13,155,104.88 for investment in renewable energy

- led to 131,049 more miles being cycled

- saved 1,352,277 miles of car travel

- produced 17,800 MWh of renewable electricity a year, saving 7,450 tonnes of CO2 annually

- led to 74,196 more miles being walked

- begun work on building projects with a value of £5,150,371

And that’s just the measurable impacts. And that’s just 21 Stories. There are many, many thousands. “Retards human flourishing”?? Quite the opposite.

“In the end”, he concludes, ramping up the patronising, “we have to say the best Transitioners can offer is an exercise in effective community building”. Firstly, that’s nonsense. But secondly, his whole argument places no value whatsoever in “effective community building”. He imagines that social cohesion will come, as we shall see, from a benign utopian socialist future, not from people learning how to wage peace in their communities, how to build connections and community, something which is seen widely as being central to improving public health, mental health, community cohesion. In these worrying times of terrorism and marginalisation, having the skills of “effective community building” may turn out to be far more important than most other skills a community could train itself to have. But for Phillips it deserves little more than a smug pat on the head.

As well as Transition he loves creating other straw men, lumping together the green movement in its huge diversity and many manifestations as one lumpen mass (I might recommend Andrew Dobson’s ‘Green Political Thought’ to help him tease this apart) and then painting it with some of the laziest stereotyping that even in the 1970s would have been outdated and somewhat bigoted. For example, he quotes, without comment, Yasmin Nair who says “the very idea that one should be concerned about privacy or dignity while shitting is one that hippy-radicals and academics mock”. What? Eh? Does that actually resonate with anyone you ever met in your time doing Transition, never mind as a catch-all for the whole movement? Hold onto your hat though, it gets madder yet.

Phillips relationship to compost toilets is just one place in this book where he completely contradicts himself. He is rather fixated on shit and our relationship to it, using compost toilets as proof of how mad Transitioners and others really are. Yet later in the book, in a section where he takes on the idea of ‘peak phosphorous’, he argues that “we need research into how we can better capture and recycle the vast quantity of phosphorous that is just left to escape … from human and animal waste…”, praising the Swedish cities experimenting with urine harvesting. We “will likely require brand new and society-wide composting infrastructure” he states, adding “this is no small endeavour”, which leads me to wonder why, then, he feels so compelled to put the boot into and to condescend those already pioneering this great idea he just had?

Similarly, the book spends much of its time having a go at Naomi Klein, in particular at some of the arguments she makes in ‘This Changes Everything’. He is particularly dismissive of her suggestion that the standard of living we need to be aiming for is that of the 1970s, pouring scorn on the very idea, yet later in the book he effuses that the 1970s “was without doubt the high watermark of civilisation”. Sometimes it’s like different parts of the book are written by different people who didn’t actually speak to each other.

As the book goes on, amid all the localisation-bashing and hyperbole, we start to get a sense of actually where he is coming from. “This small-is-beautiful localism is a remarkably pessimistic position, and certainly at odds with the long-cherished, optimistic goal of socialists of global economic democracy”. Ah. He continues:

“True planning, the kind that will actually take us most of the way to a low-carbon economy, would involve taking the power companies back into true public ownership – that is, transforming them back into the providers of public services rather than operating as de facto multinational corporations”.

He wants, it turns out, to see a centralised, socialist world, in which the state can unleash the power of technology and progress to advance humanity and deal with the climate crisis (although it’s a vision that differs wildly from other ecological Marxists like John Bellamy Forster). It is at this point where, frankly, Phillips loses the plot entirely, building to his hysterical ‘Lost’-like fantasy crescendo finale. Having accused the localisation movement of being ungrounded, he argues for a ‘principle of audacity’, “that our species must continue to achieve ever more impressive feats”. The next passage had me snorting out loud with laughter on the train where I was reading it (with apologies to the man standing next to me). He argues that we must:

“… continue to grow economically so that we can, for example, build and maintain effective near-Earth asteroid deflection systems to protect the Earth; spread throughout the galaxy so as to assure the continued existence of the species in the life-vitiating event of a local supernova; and ultimately advance to a level of technology and understanding of reality that perhaps we can figure out a way to permit intelligence to escape the heat death of the universe”.

Blimey. On a serious note though, the real challenge is not our need to escape the “heat death of the universe” in several billion years time, but rather the “heat deaths” already occurring in ever greater numbers as the world moves above a one degree rise in temperature. In spite of claiming to be motivated by climate change, presumably so as to distance himself from the Matt Ridleys and other “lukewarmer” (the latest rebranding for climate sceptics) “eco-modernists” with whom he shares many views, what does he actually offer that will turn the climate crisis round? Nuclear power and the dream of a socialist government. That is pretty much it.

But as the recent election showed in the UK, there is no hunger among the population at large for the kind of socialist utopia he proposes. Although he doesn’t suggest this being imposed through a violent revolution, one must assume that given the apparent non-starter of the democratic route, that’s the only option left open to him. What we see in Transition is thousands of communities motivated by the urgency of climate change, but not prepared to put their hope in a political model that will never happen, and so are starting to do the work that needs to be done themselves.

The hope is that this then starts to shift and influence thinking further up the political system, something we can start to see evidence of. Rather than “retarding human flourishing”, movements like Transition are giving many people their first experience of actually influencing the world around them, in a practical, empowering way, rather than some abstract political fantasy. And those steps are starting to lead to jobs, to development, to business and, yes, to ‘progress’.

“We must learn again how to weep hot tears of pride at the best of what our species can do” he concludes. Bloody right. As I visit Transition groups around the world and see the amazing flourishing of ingenuity, entrepreneurship, connection, care and brilliance, often those are the very tears that come to my eyes. Why is it that these so called ‘Promethians’ and ‘eco pragmatists’ who so hail the white heat of innovation and technology are unable to apply that same thinking to the challenge of urgent decarbonisation? Like Alex Epstein’s appalling book ‘The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels’ (which I reviewed here), many of Phillips’ arguments embody a fear of change, and a fear of difference, while slating those he targets as doing just that.

Like ‘Lost’, when I reached the end of ‘Austerity Ecology’, I felt aggrieved at the amount of time I had wasted on it. I could have spent that time doing something useful, getting on and actually doing something about climate change. Like ‘Lost’, the approaches put forward in this book will keep you waiting interminably for an ending that may or may not come, and if it does will almost certainly not play out as you imagined it would. Time is short, life is precious, let’s just start building a fairer, more just world here and now, rather than putting all our hope in distant dreams of socialist perfection and intergalactic space travel. And I never did find out how on earth you can weave a pair of pants out of carrots. Perhaps the sheer discomfort of wearing such an item might explain the curmudgeonly embittered spirit in which much of this book is written?

What I had hoped to read here was some kind of an analysis, a rigorous critique of bottom up approaches like Transition, an exploration of whether there is evidence that our theory of (bottom up) change actually works. I’d love to have read that, something that Luigi Russi’s excellent Everything Gardens and other stories was an attempt at. But this book contributes absolutely nothing of any use whatsoever to any of those discussions.

You might also enjoy Chris Smaje’s excellent take on Phillips’ work here.

Read more»

18 Nov 2015

Last weekend’s dreadful events in Paris were appalling. Like many people I am still in shock and grief, and want to send huge love and support to everyone affected, especially our friends doing Transition across Paris. I hope they are all safe. I also recognise that we live in a world with a ‘hierarchy of tragedy’, which places the suffering of those more like us above the suffering of others, so I want to recognise that such tragic events, and worse, are a regular occurrence for so many people around the world.

One key moment that stays with me was when French President Francois Hollande was interviewed shortly after the attacks and said “we are going to fight, and this fight will be merciless”. It took me back to those days just after 9/11 when the Bush administration began talking about ‘the War on Terror’ and stating that “you are either with us or you are against us”.

Today I have that same pit of the stomach feeling, further deepened by news of aircraft carriers being dispatched and airstrikes on Syria. How different might it have been if instead he had announced that his government were going to take some time to reflect on the implications of this? To invite a deeper reflection of the questions it raises?

While I appreciate that retaliation and attack are one human response, they’re not our only option. There is another response which looks to try and break the cycle that we appear to be stuck in. A response which, rather than talking, as the Director of the CIA did recently, of our now being in a “continuous war”, one without end, actually explores and seeks to address the root causes of that cycle. Reading the news coverage of recent days you could be forgiven for thinking that these awful attacks occurred in complete isolation, and that the behaviour of Western powers could in no sense have any kind of a role in creating it.

As many people, such as Chalmers Johnson, have shown, that is absolutely not the case, that our own history is full of illegal wars, occupations and worse. And as Mehdi Hasan points out, Western governments, while outraged and affronted at the idea that their actions might create such a response (forgetting that in March of this year, President Obama described ISIS as an “unintended consequence” of the US invasion of Iraq), are happy to argue that Russia’s bombing of Syria will “only fuel more extremism and radicalisation”. Hasan adds:

“The inconvenient truth is that geopolitics is governed as much as is physics by Newton’s third law of motion: “For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction”.”

While governments may not pause to reflect, and appear to have chosen to dash into a military response, we can pause and reflect. And reflect we must.

A recent study by Marte Otten and Kai Jonas in Social Neuroscience offers rich food for thought. The study looks at humiliation, which they define as “the emotion associated with being lowered in status in the eyes of others”. The root of the word “humiliation” is the same as that of ‘humus’, referring to the experience of having one’s face ground into the dirt. Some psychologists refer to humiliation as a “nuclear bomb of emotions”.

Their study concludes that “humiliation is a more intense emotional experience than happiness, shame, or anger”. Yet since the ‘War on Terror’ began shortly after 9/11, its key weapon has been humiliation. Western nations have rained down humiliation on those various corners of the world that fell into the “against us” category, in a chaotic “my enemy’s enemy is my friend” kind of an approach that is now backfiring so dreadfully (as John Pilger captures powerfully here).

There was Abu Graib, Fallujah, rendition, drone attacks, and so it goes on. Humilation upon humilation. Torture techniques used at Guantanamo Bay and elsewhere designed explicitly around creating humiliation. It felt to me at the time that the Iraq War appeared to be designed with the intention of humiliating a whole nation, a whole culture. But those inflicting humiliation tend often to be those who have experienced it, and are acting out transferring it on to others.

Donald Klein, writing about his years of research with people who have experienced humiliation in the US, writes, “I believe that humiliation or the fear of humiliation is at the root of much of the most destructive interpersonal and intergroup behaviour in this society”. For Linda Hartling, humiliation is “an experience that poisons individuals, families, communities, and whole societies for untold generations”. It is that poison that we are experiencing now in so many different manifestations.

But humiliation is a dangerous thing to invoke, something we mess with at our peril. As Otten and Jonas point out, “humiliation seems to evoke strong approach-related tendencies, most commonly anger and the inclination to take revenge”. Evelin Gerda Lindner, in a 2001 paper, notes that humiliation is the “strongest force that creates rifts between people and breaks down relationships”. In this context, given the brutality of the last 12 years since the invasion of Iraq, and the institutional dishing out of humiliation on a staggering scale began, what might we learn from this research on humiliation that might aid us in shaping what our response as citizens might look like?

Firstly, where we have a choice, we might stop electing people for whom this feels like the natural response. Leading in a way where inflicting humiliation is the natural response may usually be our experience, but it’s not the only option. In a 2002 paper in the Journal of Peace Psychology, Lindner contrasts the experience of Germany in the 1930s with South Africa in the 1980s. The deeply-felt sense of humiliation which Hitler used to build his Third Reich had consequences we are all too familiar with. In contrast, South Africa is a rare example of how dealing with the humiliation caused by apartheid was skilfully and compassionately managed. The world expected a bloodbath in South Africa as the handover from white rule began. Part of the reason this didn’t happen was, as she puts it:

“The humiliators and the humiliated sat down together and planned for a society in which “both Black and White” could be “assured of their inalienable right to human dignity”.

She was writing shortly after 9/11, and noted, prophetically, “if the 21st century is to be shaped by the example of Mandela, the part played in human relations by humiliation must be better understood”. What might a more Mandela-inspired response to the awful events of last weekend look like?

Later in her paper she adds, “it is easy to concentrate on perpetrators and their wrongdoings, but difficult to accept one’s own potential contribution to the process of humiliation”. This echoes the closing paragraph of Medhi Hasan’s article:

“Yet we avert our gaze from the “glaringly evident” and pretend that “they” – the Russians, the Iranians, the Chinese – are attacked for their policies while “we” –Europe, the west, the liberal democracies – are attacked only for our principles. This is the simplistic fantasy, the geopolitical fairytale, that we tell ourselves. It gives us solace and strength in the wake of terrorist atrocities. But it does nothing to stop the next attack”.

Already we see those whose response to the attacks has been to suggest adding more humiliation to the experience of refugees who have experienced little other than humiliation for some time. Lindner talks, prophetically, of humiliation as “weaponry”.

The question I am sitting with is how as individuals, and as those involved in Transition, we might play any kind of a role in starting to break this cycle of humiliation leading to response which elicits more humiliation and so on and so on and so on? As individuals, there’s lots that we can do to tackle humiliation in our daily lives. We can become more mindful about times when it becomes our own response. And we can support those around us experiencing humiliation to, as Lindner puts it, move from being “reactors” to being “actors”.

She writes “self-humiliation can be a central factor and must be openly faced if there is to be constructive change”. For those of us bringing up children, one of the most powerful things we can do is to never humiliate our children, and to bring them up with the inner resources that they can draw on in potentially humiliating situations. For me, as a father, not humiliating my children has been a conscious intention from the very outset, unlike, sadly, some of my peers.

For me, large parts of my schooling were built on foundations of inbuilt humiliation, an experience that for many continues to be the case. Whenever I hear anyone saying they experienced an education like that but that “it didn’t do me any harm”, it makes me wonder how deep our denial of humiliation runs as a culture, and how it influences what plays out and how we act.

Hartling argues that one of the key antidotes to humiliation is an approach called ‘Appreciative Inquiry’ and suggests that some key elements of it might be:

1. Practicing relational-cultural awareness:

- Meeting others in mutual respect (rather than making them earn it).

- Being mindful of one’s intended and unintended impact on others

- Appreciating that each member of the group is connecting across differences in language, culture, disciplines, interests, experiences, and many other differences that can make dialogue rich and challenging.

- Being attuned to time and timing by checking agreements about the meeting schedule throughout the program.

2. Listening each other into voice:

- The process of listening and speaking is bidirectional; we can literally listen each other into voice. That is, all participants can respectfully help others find ways to clearly express their ideas

- Creating a context of collective curiosity and collaboration.

3. Waging good conflict

- Disagreeing without being disagreeable, without contempt or disrespect.

- Questioning what’s wrong with being wrong. Sometimes acknowledging that one is wrong is the pathway to a new insight

- When in doubt, asking for feedback.

- When needed, practicing the power of apology

4. Creating better connection through reflection

- In addition to reflecting on what has been collectively accomplished, reflecting on how this work has been accomplished as the meeting progresses.

- Being responsive to each other and making adjustments to various aspects of the meeting as needed.

- Acknowledging and honouring individual and shared efforts to foster an appreciative, humiliation-free learning environment.

- Joining with others as active partners and co-creators of the meeting experience.

5. Taking our work seriously, but taking ourselves lightly.

- Employing humour to laugh with each other is always encouraged and encouraging.

Appreciative Inquiry is a tool used by many Transition groups, which is why reading the above might feel so familiar. We can create (and many groups already have) a group culture in which humiliation has no place, or at least one where if it does occur, the culture is able to recognise it and support intervention, responding appropriately. Ensuring that we have good group processes in place and well-facilitated meetings and projects make a huge difference.

In the same way that Jamaica Plain New Economy Transition in Boston were the first to raise the question of what Transition might look like if it were viewed through the lens of being a public health strategy, I would like to suggest that minimising humiliation might be another possible lens. It may yet turn out to be one of Transition’s most valuable legacies.

Donald Klein, writing in the US context, says:

“Denial must be removed and the deleterious effects of the humiliation dynamic brought to the forefront of attention in American society. We must be able to recognize, acknowledge, and talk about this dynamic in order to reach the point of being unwilling to participate in it, either as humiliator, victim, or bystander. If we are to achieve community-building connections between individuals and groups who differ markedly from one another in values and social orientations, the objective must be to connect people and their experience in ways that include both the experience of difference and feeling put down and demeaned by one another by virtue of those differences”.

When I present ’21 Stories of Transition’, with its 21 Stories from 39 Transition groups in 15 countries, I ask the audience to reflect on what they see as being the threads that run through the stories. The answers each time touch on some common things, but also some that are particular to that talk. But no-one has yet discussed how those stories represent a bottom up strategy through which people and communities might begin to consciously try to break the cycle of humiliation that we see playing out before us. It is certainly something I will start mentioning now.

So long as our default setting is determined by humiliation and depends on inflicting humiliation, we will continue to cycle and to undermine humanity’s ability to flourish. Breaking that cycle is vital. It starts here. As Martin Luther King put it:

“Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that”.

References not included in links above.

Lindner, E. (2001). Humiliation: Trauma that has been overlooked: An analysis based on fieldwork in Germany, Rwanda/Burundi, and Somalia. Traumatology, 7 (1).

Marte Otten & Kai J. Jonas (2014) Humiliation as an intense emotional experience: Evidence from the electro-encephalogram. Social Neuroscience. 9:1, 23-35.

Images from author’s recent visit to Paris.

Read more»

16 Nov 2015

Today Erik Lindberg of Transition Milwaukee reviews ’21 Stories of Transition’ (available here).

Rio, Kyoto, Copenhagen, and Paris

In December, representatives from governments from across the Earth will descend upon Paris in hopes, once again, of hammering out a global agreement to limit carbon dioxide emissions to the point where human civilization might expect a reasonable chance of survival. Although there is greater urgency that ever and growing consensus that “something must be done”, no one really expects a meaningful, enforceable, and ultimately effective agreement to emerge from Paris. Even if an agreement is reached, judging from the pre-summit carbon pledges of 147 nations, proposed reductions are not nearly enough to prevent a 2 degrees centigrade rise in global temperature.[i] Just as carbon emissions continued to rise after Rio, Kyoto, and Copenhagen, it is hard to imagine how the Paris summit might represent a true turning point, even as we move closer and closer to a point of no return.

Meanwhile, in villages, neighborhoods, and communities, large and small, from across the globe, action is being taken and hope, nevertheless, lives on. Countless groups and organizations are heeding history’s call and taking matters into their own hands. With open hearts, open hands, and open minds, people on every continent and from every walk-of-life are coming together to create real solutions. They are sharing, cooperating, helping, and taking responsibility for the future. The global ecological and resource crisis, as our official leaders regularly demonstrate, could easily incite retrenchment, competition, and the fearful protection of privileges that will ultimately mean nothing. But it could, as ordinary people are proving, be the inspiration for a great imagining unlike any the world has ever seen.

It is this Great Imagining, in the face of a global crisis and official paralysis, that I want to talk about here. I hope, even plea, that my friends, acquaintances, and readers will take another look, while asking themselves, “what can I do?” “How can I be a part of this?”

The grassroots response to climate change, resource depletion, growing inequality, and widespread global injustice comes from every quarter. But one of the greatest sources of inspiration has originated from the International Transition Movement, a loosely-united assembly of communities following the lead of a humble and mild-mannered English community organizer, teacher, and leader of considerable genius named Rob Hopkins. About a decade ago, Hopkins set out to imagine how we might build just and sustainable communities that would serve the real needs of everyone. The result was first a Transition Town, and then another. Following these heartening initiatives, Hopkins put together The Transition Handbook, whose message of community, local resilience, and the good life that renewed communities might afford remains intact throughout the revision of approach and tactics seen during the intervening years.

In advance of this year’s international climate conference (COP21), Hopkins has assembled into a single collection 21 Stories of Transition, highlighting some of the accomplishments that Transition Groups from around the globe have made. Hopkins changed my life with his Transition Handbook and I’m getting that feeling, once again, that the 21 Stories might provide another watershed moment for me. It’s time to make another big push here in Milwaukee.

Beyond Carbon

Read in the context of the Paris Negotiations on climate change, the 21 Stories are hardly what one might expect. But that is the hidden genius of the Transition Movement. Sustainability, as Pope Francis has recently argued, is not just about atmospheric chemistry rather it calls for a new paradigm that integrates the ecology of all life with social justice and an inner transformation of human beings away from competition and consumption towards full and authentic development. In this vein, Hopkins and his collaborators share accounts of a caring group in Devonshire, the rise of alternative currencies in communities such like Brixton and cities like Bristol. There are accounts of community-driven and financed energy collectives, and lots of tales of local food production and distribution; Transition Streets, like many of the featured projects, are geared towards neighborhoods uniting to find a way to reduce their carbon footprints. But equally important are stories of rainwater harvesting in the Brazilian megatropolis of Sao Paulo, a repair café in Pasadena, a Free Store in Pennsylvania, or the growing emphasis on crowd-funded local entrepreneurs.

One especially inspiring story tells of Greyton Transitioning Town in South Africa. Here, local volunteers have built two businesses, which are used in large part to finance an “EcoCrew environmental awareness programme,” focusing on educating children and giving them a leading role in the creation of local food, parks, and recycling activities. One of its most significant roles, however, is the social integration in this part of the world in which the open wounds of apartheid are widely visible. Although the commitment to the environment is central, as with many Transition projects, the most impressive results come in the form of small-scale civic development, of a child finding purpose, or a circle of care gathering up the lonely.

As Hopkins explains, this sort of caring community and concern with social justice are central to Transition’s ideals, as are principles of supporting each other, with a focus on “qualities like enjoyment, self-development, a sense of belonging and the dignity in work” (Twenty One Stories, 13). The installation of solar panels or wind turbines makes immediate sense if our most pressing challenge is to decrease the burning of fossil fuels, and it takes only a primer on the role of fossil fuels in industrial agriculture to see why small-scale local farms and community gardens loom so large in the imagination of the Transition Movement and in the 21 Stories.

But the emphasis on community, the celebration of place, or the enhancement of human dignity, helps explain why Transition ranges far beyond issues of carbon emissions. It is in this spirit that we hear about a Free Store, in which people donate what they don’t need and take what they do. The same goes for an account of people in Pasadena showing up periodically to darn each other’s socks and straighten someone’s bike tire, or Transition Totnes’ grass-roots attempt to augment dwindling county services for the sick and needy. Yes, the reusing and repair of existing products is “good for the environment,” but the value of community action is worth far more.

About the Carbon

It is easy—perhaps too easy—to fault our official leaders with cowardice and inaction. But when we send national representatives to an international global warming summit, they are sent with an impossible mandate: protect our national privilege (or increase it), preserve our way of life and our every expectations for increased material acquisition, maintain the economic growth required to keep national banking systems intact—oh yeah, and cut domestic carbon emissions (but not more than others nations are willing to cut theirs).

We blame our leaders for their shortsighted calculations. But part of the reason these climate agreements fail to make meaningful change is simpler than is generally acknowledged, and lives, hidden and unseen, in both the hearts and homes of nearly every citizen of advanced economies and industrialized democracies. It is about what we want, expect, and demand. It is not possible to maintain our way of life, maintain economic growth, and cut carbon emissions. Nor is it possible to engage in competitive statecraft and reduce the burning of fossil fuels.

There is, then, a crucial nugget of truth, largely ignored in the mainstream press, in what we have gotten from Rio, Kyoto, Copenhagen, and probably Paris: a sustainable future requires a contracting economy, a slowing down of production, and a broad curtailment of individual consumption. If our leaders presented us with this, they’d be hung by their heals in the village square. We want our leaders to cut global carbon emissions; but we also want a way of life that only fossil fuels can deliver. Until we understand the contradiction and begin to untangle the complexities of a transition to a low energy way of life, we should not expect too much from our elected governments.

Consider, as a sort of mental exercise, what would happen if we were to switch off the fossil fuels and run on available renewables as of today: as it turns out, we’d have to reduce our consumption by about 90%. That means getting rid of 90% of what you have and 90% of what you do and where you go. Develop these renewables at a plausible rate, on the one hand, and reduce our atmospheric carbon emissions at a meaningful rate (the one at which we and other large mammals may survive at a robust level), on the other, and we’re looking at a 75% reduction in economic activity over the long and permanent run. We might quibble about the exact figures; but there is no question of running our current, competitive, growth-dependent, and leisure-based way of life without the use of fossil fuels—those same fossil fuels that will kill us off if we cannot kick these habits of competition, growth, and, leisure in the form, mainly, of consumption.[ii]

Sure, we hear the promises of “sustainable development” and “green growth.” The abiding faith—or is it the lack of any plausible alternatives?—is that we can take our current systems of production and distribution and plug them into a new (sustainable and consequence-free) fuel source with only minimum disruptions. But, at the same time, international carbon-cutting agreements are rejected for one, and only one, reason: that they will hurt our economies, slow down the rate at which we make, buy, and sell goods. These agreements will force compliant nations to lose their competitive advantage to nations that don’t comply.

We may like the idea of an international climate agreement, but we probably wouldn’t like consequences of a meaningful one. And so our leaders give us a watered-down and face-saving compromise. Our way of life and our national power and prestige, it turns out, is fossil fuel based. We can’t have it both ways. “Your money or your life,” Barbara Kingsolver once quipped, “is not supposed to be a rhetorical question.” But that, in effect, is the decision we have to make, but have been unwilling to accept.

Viable Alternative Systems

Our current systems, as Hopkins puts it, “are meant to support and provide for us, and to enable us to flourish and thrive” (9). But they cannot survive in a low carbon or sustainable world. This is the basic knot that must be untied for us to get a real climate solution. As Hopkins rightly points out, these systems are already “failing us spectacularly,” but if we remove the fuels–coal, gas, and oil–which provide them with what remaining benefits they have, they would fail us entirely. This is true even if we attempt to make a slow transition to new fuels, while attempting to keep the old systems in place. As a practical matter, we don’t have the capacity to feed, cloth, and house ourselves without massive use of fossil fuels. Our current systems, let me say again, cannot survive in a low carbon world. We need new systems.

We are of course talking, here, about things like a food system run on an industrial model, which requires massive fossil fuel inputs, while poisoning us with sugars, toxins, and fats. We are talking about an economic system based on perpetual growth, a social system based largely on competition, an education system that trains children to make money rather than things, a system of technological development that accepts no limits, and a list could go on and on. Yes, these systems have created some verifiable marvels, but our appreciation of them also requires that we bracket-off their collateral damage and disconnect their spectacles from their lethal nature. For all these other systems are high-energy systems. They can work quite well, if unevenly, but only if fed with limitless amounts of consequence-free fossil fuels. All our modern industrial systems, this is to say, are dependent on the mother of unsustainable systems—the energy system that, quite literally, is threatening to do us all in.

While the best and the brightest attempt to hold these failing and clearly lethal systems together with a high-sounding and self-impressive version of duct tape and bailing wire, Rob Hopkins and the Transition Movement set out over a decade ago to engineer replacement systems that might actually work under lower energy conditions. As Hopkins as recently written, “It is to building that viable alternative that I put my shoulder. It is celebrating that viable alternative that will be the focus of my time in Paris in December.”[iii]

Instead of finding support and nurture from systems requiring chemical inputs, intricate parts manufactured across the world, and panels of technological specialists flown in from the nearest city, these “viable alternative” systems are overwhelmingly local. They are powered by muscle and basic tools, and require no more specialization than one might find in one’s neighborhood. They replace wizardry with local wisdom, and at root are based on the lost arts of community and cooperation, with which almost anything of immediate use and simple beauty might be nailed, stitched, and mortared together.

The easiest of these replacement systems to grasp is the food system, perhaps because food’s fundamental status remains embedded in our sense of self, despite the best efforts of the packaging, the branding, and the barrage of advertising harassment telling us to eat the corn-fructose combination with the tiger mascot instead of the one represented by the cute bears. Instead of depending for one’s daily bread on the whims of international finance and commodity markets, Monsanto intellectual property, and a whole heap of chemicals we can scarcely pronounce, let alone digest, most people will often gravitate towards a local food system when given the chance. Growing food, after all, is something humans have done for millennia, and a local and sustainable food system only requires simple things that we can see, smell, touch, and, of course, taste. But producing enough to live on also requires practice, hard work and commitment, as well as some fundamental changes in the overall economy.

Simplicity, common sense, and community self-reliance, nevertheless, are the hallmark of the 21 Stories, as well as the thousands of projects not featured in the book. Instead of waiting for someone to build a 250 miles per gallon super-car, why not get out the old bike? Instead of waiting for some new ultra-green nano-technology to do all our daily slicing, dicing, pressing, closing, communicating, heating, and cooling, why not find someone who can sharpen your knives, solder that loose wire, lend you a fan, or fix your windows? Instead of shipping some faddish culinary delicacy from the South Pacific, why not prepare salvaged food that someone else is throwing away? Instead of stretching your tight household budget to include gym membership and special energy shakes, why not get together with your neighbors, dig in, plant a garden and keep a few chickens? Instead of waiting for the next financial crisis and the sudden loss of a lifetime of savings and investment, why not create a local currency with which you can buy and sell some of life’s basic necessities no matter what else happens?

From this perspective, the rise of local currencies, the Pasadena Repair Café or Fishguard’s Surplus Food Café begin to look less like counter-cultural pottering and more like a serious attempt to find something that can, and will, work. The rise of local farms, food markets, community gardens are only the tip of the iceberg of this imaginative reengineering of our life systems. The creation not only of local currencies, but a whole network of local and community based responses to the increasingly undependable whims of the global economy, of government budget cuts, and unpredictable employment lies at the heart of Transition. One of its keywords has always been “local resilience.” While the terms of Transition’s resilience-based self-description tend to be based in the language of care, or small-scale entrepreneurial innovation, or community action, or the envisioning of a better future for one’s family and neighbors, underlying it all is a serious questions: how could you get by on an energy diet one fourth the size of your current one? What would you do if the trucks stop running or the banks shut down? Who can you turn to for help?

The Great Imagining

If, however, we suppose that the power of the Transition Movement lies primarily in its practical ability to engineer and implement new, replacement systems, then we sell it far too short. The genius of the Transition Movement, it seems to me, is more subtle yet also more fundamental. It presents a fresh and alternative way of seeing—and of valuing. It has not only imagined a new set of possibilities, it has taken the next crucial step and created working models for the rest of the world to see. The 21 Stories represent only a selection of these working prototypes and provide a taste of this other way of seeing, valuing, and relating to others and the Earth.

This way of seeing is the most important component that has been missing from international climate agreements.

Social psychologists have wondered at the resistance of many conservatives in the Anglo Saxon world to the science of global climate change. What force of denial could lead to the dismissal of undisputed science? The conclusions of this psychological research tell us something very important about belief and social and political change in general. The greatest source of conservative denial is not, as some would have it, based on their inability to accept the scientific evidence. Rather, it has to do with a more general picture about how the world works and should work that conservatives hold dear. As Naomi Klein has suggested, if conservatives “admit that climate change is real, they will lose the central ideological battle of our time—whether we need to plan and manage our societies to reflect our goals and values, or whether that task can be left to the magic of the market.”[iv]

Liberals, in contrast, have (as conservatives like to point out) been arguing for decades that we need to manage our economy more vigorously. The idea of an international agreement whereby governments cap carbon emissions and invest public money in renewable energy is not only acceptable to many liberals, it actually represents a form of progress that liberals have been hoping for all along, with liberal economists like Paul Krugman naively arguing that a renewable energy revolution is just what we need to spark our economy and ignite another century of economic growth. To put this another way, using another term from social psychology, while liberals tend to like the solutions (as they conceive them) to climate change, conservatives have a distinct case of solution aversion, which is strong enough to taint any associated scientific evidence. So repugnant is a solution that threatens the sanctity of the market that they can’t bring themselves to accept that there is a problem in the first place.

This same dynamic can, surprisingly, be seen in the same liberals who are celebrating the idea of international climate agreements. Although they are jubilant at the prospect of investing public money in clean energy or fashioning a “New Deal” based on energy transformation, their disposition turns sour—and even downright nasty—when these same anti-denialists are confronted with the possibility that wind turbines and solar panels will not be able to replace the power (and the economic growth) we have enjoyed from fossil fuels. Regardless of the data and mathematical evidence, these same critics of conservative climate deniers often reject any notion of the limits of renewable energy on the very face of it, supposing (I can attest first hand) that anyone who even suggests such a possibility must be an enemy of humanity itself.

Part of this incredulity has to do with the liberal faith in continued progress, the power of human inventiveness, and the overriding hope that all people might one day be freed from kinds of difficulties and indignities that the middle class European and American lifestyle seems to afford. Part of it has to do with most middle-class people’s dislike of a solution in which middle class comforts and privileges and white-collar skillsets play a decreasingly central role. That we might become more agrarian and less automated or more interdependent and less autonomous, that traditional inhibitions on the freedom of consumption might have some sense to them after all, that Silicon Valley might be turned someday into pasture—all this strikes many a progressive as the height of defeat or regression into a dark past. Progress has always (or for a few hundred years, at least) meant the transition from agriculture to industry, and from industry to some largely imaginary global technological post-industrialism. Few are prepared to embrace an international climate agreement that threatens this trajectory—which, it turns out, a meaningful limit on carbon emissions would, in fact, do.

I am tempted to say that liberals, like conservatives, are suffering from solution aversion; but I think we are dealing with something even more fundamental than that. It is not so much that they (like just about everyone else in industrial society, liberal and conservatives alike) would not accept a solution that involves the powering down of industrial society; rather, for most, this is simply unimaginable. If we can’t live with current levels of comfort, convenience, choice, mobility, and leisure, we may just as well give up. Only a plan that promises increased industrial development and lower carbon emissions is, according to this view, conceivably acceptable. No such plan exists, nor can it. Industrial development and sustainability are incompatible, the liberal faith in green growth notwithstanding.

This is where Transition and its Great Imagining can step in. Transition, with other similar movements, has recast the very notion of progress, value, and good. They have shown how the thriving of humans is not dependent upon industrial development, and therefore, has demonstrated how human well-being is, in every sense, compatible with radically decreasing use of fossil fuels It presents a solution to climate change which might overcome the initial aversion that liberals, conservatives, and everyone in between all have for anything other than industrial development. As Hopkins explains, “The systems that are meant to support and provide for us, and to enable us to flourish and thrive, are failing spectacularly. This is increasingly self-evident to people, wherever they are within those systems. Yet all over the world, in creative, passionate, and brave ways, and motivate by a tangible sense of what is possible, people are coming together to create something else. Something so much better” (9). Whether or not Hopkins was thinking in precisely these terms when he wrote this, these people are providing an alternative that imagines the unimaginable while easing solution aversion.

This, I think, is why when I first read the Transition Handbook in 2008, it took my breath away; it was a revelation–for it at once presented a clear and unvarnished understanding of our current predicament in relation to fossil fuels and their lethal side effects, alongside a positive and hopeful vision for a future free from our current and unhealthy addiction to fossil fuels. Previously, I too would have had blank mental spaces for a world in which we had not replaced our energy from fossil fuels with some alternative. Nothing existed outside of this possibility beyond some hazy and disconnected images of stranded vehicles and abandoned buildings. The Transition Handbook filled these blank spaces with life.

As Hopkins wrote in The Transition Handbook, “the key message here has been that the future with less oil could be better than the present, but only if we engage in designing it with sufficient creativity and imagination” (77). This better future, then, is not better only because it isn’t lethal to the very viability of our species, but because it can create just, humane, cooperative, and community systems in which we might truly thrive. Or as Richard Heinberg put it, even as energy and the economy come to an industrial peak, there are many things of even greater value that are not at their historic peaks, things such as community, satisfaction from work well done, intergenerational solidarity, cooperation, happiness, ingenuity, artistry, or beauty of the built environment.[v] The Transition Movement reminded me of the power of community, the value and pleasure of manual labor, the basic fact that things don’t make people happy—nor do comforts. Rather, other people do, as does a sense of purpose, something to believe in and to celebrate. None of these more basic human goods required fossil fuels, nor substitute wind turbines or biodiesel.

This, in short, is the message that the Transition Movement has for COP21 and for the rest of the world—that we can re-envision a bountiful world that is compatible with the environmental and atmospheric requirements of life on Earth. 21 Stories of Transition shows us what this world might possibly look like. It shows that it is not only possible, but that it is already underway and that those who are taking action are thriving and are full of life, purpose, and joy.

[iv] Klein, Naomi. This Changes Everything, p. 40

[v] Heinberg, Richard. Peak Everything: Waking Up to a Century of Declines. Gabriola Island, BC, Canada: New Society Publishers, 2007, p. 115.

Read more»

12 Nov 2015

With fewer than three weeks to go until the start of COP21, the UN’s climate negotiations in Paris, a question arises: Will this gathering make the slightest difference? For Rob Hopkins, editor of a new book from Transition Network, 21 Stories of Transition, answer is yes – but a different kind of yes than the global leaders meeting in Paris probably have in mind. He wants decision makers to reimagine their role as being ‘community enablers’ whose task is to deepen, connect and extend initiatives that are already out there. A huge upsurge in transformative local projects is evident around the world, argues Hopkins; the priority is not for global leaders to start things off from scratch – still less, to tell people what to do.

Although Hopkins says we should not expect a ‘Great Change Moment’ at COP21, he does compare our situation today to East Germany before the Berlin Wall came down. Right up until the last minute, Hopkins reminds us, that country appeared to be robust, powerful and permanent. In reality, as its sudden collapse testified, it was ‘holed below the waterline – undermined by the number of young people defecting to the West, corruption, rigged elections, and much more’.

Today, too, says Hopkins, “Something brilliant and historic is already underway. Our message to the Obamas, Camerons and Merkels of this world is that it’s already happening”

Caring Town Totnes, in England, for example, although unique to its context – is relevant for thousands of other communities.

This collaboration of more than 70 local public, voluntary and private health and social care providers have a shared objective: to ensure that every resident of area, and especially the most vulnerable people, know where to access support and have a range of affordable options to meet their needs.

The thinking is that health and he work well being are not best thought of as a something ‘delivered’, like a pizza, by a distant supplier. Community-based health and prevention emerge, instead, from a collaborative network of professional and voluntary groups and organisations. The social design task is to create the conditions in which such diverse actors camay collaborate.

This shift of emphasis away from biomedical ‘factories’ such a big hospitals is exemplified by Greenslate Community Farm.

This once derelict rural cluster is being transformed into a multi-acitivity community hub. Funded by Public Health England, it provides a meeting place for people recovering from drug and alcohol addictions and others special needs.

Therapeutic activities at the farm cross-subsidise growing activities. Eighteen acres of former barley field are now a regenerating woodland that is being coppiced and replanted. Old farm buildings have been repurposed as a schoolroom and shops. A community energy company, a vegan catering wagon and a charcoal maker use the farm as their base. Future plans include a new straw bale building to house a professional kitchen, a community bakery, a cafe, a dairy and offices.

A pixellated geography of farming is also emerging alongside this diversification of farm activities. In Liege, in Belgium, an archepelago local food enterprises are being run, connectedly, as ‘learning network of microfarms’ in a joined-up ‘Food Belt’ around the city.

In a city with a long heritage of industry and steel production, much of the land within the city is too contaminated for growing food, so the idea is to reconnect the city with its peri-urban land, and to use the revitalisation of local food production to reimagine the local economy. The vision is for Liège to be surrounded by microfarms of 3-4 hectares (8-10 acres), creating many jobs. In London, the Crystal Palace Patchwork Farm is based on similar principles.

Energy and Money

The two invisible but all-embracing backstories of these new times – energy, and debt – are also being tackled by small projects with the potential to make a huge difference as they connect, help each other, and multiply.

Community energy projects, especially, enable communities can start to take back control of their economy, and their energy supply. In the UK alone, over 5,000 community groups have set up community energy schemes since 2008 – and the start-up rate is increasing. In Germany over 50 percent of new renewable energy installations are in community ownership. Community Energy England reckons the energy landscape could be transformed – “from the Big 6 to the Big 60,000‘ – if the regulatory system were to be opened up.

A simple business incentive explains the shift. The priority for a community energy focuses is to cover operating costs rather than maximise profits for distant shareholders. A community energy enterprise therefore ploughs far more income back into the local economy than large renewable energy developers. This ‘multiplier effect’ also drives the spread of local money systems.

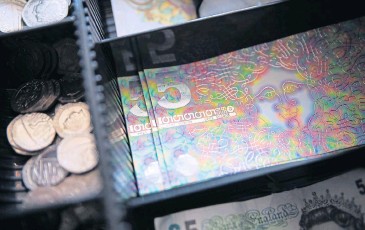

Money spent with local businesses circulates more times and leads to greater benefits for the local economy. The Brixton Pound, for example, calls itself “the money that sticks to Brixton”. The Bristol Pound, launched in 2012 represents a step up in scale for a local currency. Bristol’s Mayor takes his full salary in Bristol Pounds, and local people can pay their local taxes, pay their energy bills, and buy tickets on the buses and trains using the local notes.

Although most of the projects in 21 Stories are stand-alone initiatives, one town-wide programme stands out. Ungersheim, a village in the Alsace region of France, has become a Fair Trade town; launched a local currency, ‘Le Radis’ (the radish); mapped the biodiversity of the area in an ‘Atlas of Biodiversity’; returned a former waste heap, created by mining, to nature; installed a120m2 solar thermal installation at the swimming pool; changed all public lighting in the village to low energy bulbs, leading to a 40% reduction in energy use; and completely banned all pesticides and herbicides in public areas; the local primary school now serves 100% organic meals – much of them sourced locally;

Jean-Claude Mensch, Mayor of Ungersheim, recognised in the Transition approach “a different, inclusive and fraternal economic model”.

Originally posted at John’s Doors of Perception blog.

Read more»