Archive for “Originally posted on Transition Network” category

Showing results 51 - 55 of 383 for the category: Originally posted on Transition Network.

1 Feb 2016

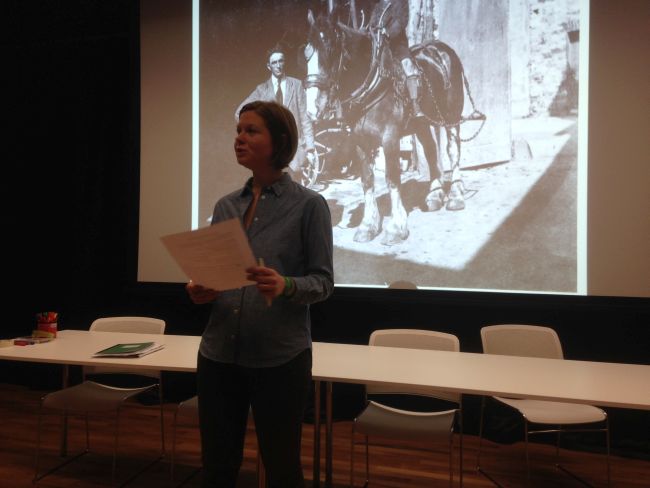

Chrissie Godfrey was formerly a co-ordinator of Transition Town Taunton (which she co-founded in 2008), but in 2012 suffered from a serious case of burnout. We asked her to tell her story, and we are deeply grateful for her honesty and for sharing her experience:

“When you first come together with other like minded people, when there’s a very pressing issue at hand and you’re learning more about it than you thought you’d ever learn, there’s a real energy around wanting to be a change-maker and wanting to make something happen. It’s a very exciting time when there’s a new group and there’s all sorts of possibilities out there. So even though the theme is burnout, this starts as actually quite a positive story.

The thing I want to say upfront is that any burnout was entirely of my own making. It wasn’t that Transition did this to me, it just so happened that at that time I was quite heavily involved in Transition, but there were other things going on in my life as well, including caring for a relative who was having a really tough time at the time as well.

I was thinking about what is it that creates the conditions for potential burnout to occur, and that maybe there’s something about personality types and particular skillsets that might end up being vulnerable to burnout, so this is a little thumbnail ‘why me’, because other people have avoided burn out.

People who are attracted to Transition are often those who can see opportunities. They can see Transition possibilities and they get very excited by those. They might be people who are accustomed to doing or to making things happen or to organising things. They might also be people who are quite good at networking, quite good at being unafraid of talking to people they don’t know or standing in front of a crowd of people and talking about stuff that they are passionate about.

There is a combination of people who can see opportunity and aren’t afraid to say “let’s have a go at this then”, plus being in other networks where people also have ideas. What it creates is a lot of things to say yes to. There’s a lot of us in Transition who love to say yes. You get an idea, it’s so exciting, you want to roll with it, and then there’s another idea and you can see how it links to idea number 1; then somebody puts their hand up and says “how about if we build in this bit” and it seems fantastic.

There’s a real sense of momentum that can build up quite early on in a group which is just brilliant. Relationships in the group are starting to flourish. In our group it felt sometimes like we were riding a crest of a wave. The Transition Network itself was quite new, and there was a huge amount of what I like to call the ‘energy of yes’.

What happened in our group with this sense of momentum was that a couple of us, again because of our particular work experience, got quite good at building ‘credibility’ with some local decision makers, movers and shakers. In our case that was definitely the local council. It was fun – it was fun being invited in to talk to the Chief Executive, and fun having one of the senior officers allocated to you to say – yes, let’s do some exciting work with every employee of Taunton Deane Borough Council.

We did loads of awareness raising workshops with everyone from the chief planning officer to the legal secretaries to the guy who drives the truck to pick up the dead leaves. It was absolutely brilliant. Because of that, we started to get quite a strong local profile. As a group, we would also turn up to stuff. We made sure we were quite visible.

Then, there’s something about wanting to be a magnet. You want to be a bit of a honeypot because you want loads of other people to come and join in and get involved. However, not all the things that you hope for actually happen. Whilst we had an amazing core group, which grew over time, ‘loads of people’ didn’t turn up to help. We had to learn to accept that there are so many different flavours of getting involved in Transition that may not mean actually joining your group.

I’ve started to think of it a bit like a family: you’ve got the family elders who are the ones who hold the centre. They hold the fort and are the decision makers, they’re the hosts for things. And then you’ve got the family members who want to be around you, who might like to turn up for a dinner party or Christmas and roll their sleeves up and do a bit of the washing up, but who disappear again back to their own lives.

Then you might have what I think of as the people down the street who just want to come once in a while for a cup of tea, just a casual drop by, no big commitment. Finally, you have your next door neighbours who don’t necessarily want to live in your house but they do want their house to be a bit like yours. These I think of as the other influencers in a town.

So we discovered that we had a core group of elders, who in our case held the centre, and then learned to work with the fact that the family members might want to turn up, but they won’t necessarily want the level of responsibility or time commitment that might come with being the elder…which was fine, except that by creating a lot of momentum, with a profile that’s visible, with more and more people are asking you to get involved in things, for me I reached a kind of tipping point. With my own internal push to sustain this momentum, I started to feel as though there was an entity that had got out of control.

As I say, there were other things going on in my life as well, but I look back on this time as a real tipping danger point. I wanted, in this interview, to flag up some of those dangers in case they resonate with anyone else.

One of these is that despite ourselves we can almost be drawn into the notion of a growth model, because we always want to do more. We want to be a bit bigger, we want to be a bit more visible, do another project. Because you’re part of a network and you’re always hearing stories about what people have done all over the world, which is obviously inspiring, there is a sense of it setting the bar quite high. Certainly for me on a personal level, I fell into a little bit of a trap of ‘unless I’m doing more it’s no good, it’t not enough’. Back to personality types – those people who say yes, often feel they ought to say yes more and yet again.

Then, there’s also something about the fact that even though it’s a voluntary group you can end up finding yourself in very professional contexts talking to other professionals and yet you’re sitting there without a job description (or pay!). So you have no boundaries over what you’re doing with this Transition gift time. You’ve got no external line manager saying “I think you’ve done enough now, that’s plenty now, you’re exceeding what you need to do”. Again, it’s a character thing, but that can really lead to self-exploitation if you’re not careful.

So there is a problem, if you’ve got people like me in the group who often say yes to things, you can end up with a group with unrealistic expectations of what it can handle. And being a voluntary group we didn’t do things that you would do if you were paid to work in an organisation such as proper project assessments, or clear role allocation, or sitting down and thinking about what the time commitments or skills would be needed. We’d just go “oh yeah, we’ll have a go at that”. And I do take a lot of responsibility for this.

It ended up that we said yes to things I really wish we hadn’t. The biggest one of these was the LEAF project (Local Energy Assessment Fund). This was a fund of money to help people in local communities get a better understanding of the energy needs of the households where they lived, and initiate projects around that. The problem was that applications were invited in just before Christmas, the decisions were to be made in January and then all of the grant money had to be spent by the end of March. And so all of the things I was saying about looking at a project and having the space and time to think through whether we can handle it, what the implications on our time might be, there was such a time pressure to go for this grant at all – and I did, and we got the money – that I nearly killed myself actually trying to deliver the project because I didn’t check out whether we had the people in the group willing to do the work.

Totally my own fault, but there was something about the system where there was this massive opportunity that I wanted to say yes to, but the time pressure was such that there wasn’t time for proper thinking back at grassroots level. I paid the price for that as it was absolutely knackering. Most of that project was delivered in the year where I finally collapsed and fell apart. It’s something for groups just to be mindful of, the tension between the speed at which the world works, particularly the world of grant aid in this instance, and the speed at which a voluntary group can realistically just have time to think and check out and test how much ‘energy of yes’ there is going on.

The other thing I have to ‘fess up to is that finding myself being a change maker is a bit of an ego ride – that happened for me, I’m not a saint. There’s something seductive about potential and wanting to say yes and wanting to be able to make change that matters to you. I came a cropper because of it, but I’m sure I’m not the only one out there in the Transition world who might resonate with that sense of – it is seductive to be able to do this, I want to make the change happen.

And I have a question: what do we mean by leadership in a Transition context? It’s almost like leadership’s a bit of a dirty word because we’re trying to be equitable and collaborative. Yet different leaders – if that’s even the right word – facilitators, motivators, whatever, will pop up from the mix in different places and leadership can sometimes just happen without it being thought through or talked about. What does that mean if I’m going to take a lead on this? What kind of leadership do we want for this particular piece of work?

Because we never talked about it, I think again because of my character and personality I probably took on aspects of leadership in the group which in the end became expectations of the group of me that I then found very hard to break. So it got into a little ‘Chrissie will’, because Chrissie always has, rather than stopping and going – hang on a minute, how did I get here?

There’s also another thing that contributed to my meltdown, which is that this kind of work can actually make you feel very vulnerable. Not everybody out there loves what you’re doing. I can remember when we were inviting people to train as home energy auditors and had quite a lot in the local press at the time about different things you can do to reduce your energy bills etc. I put my home phone number in the article because if people wanted to come to a particular public meeting I was going to be the point of contact.

I had a landlord ring up who screamed down the phone at me for about 10 minutes about how dare I be insisting on all this insulation because in his properties he tried to do that and all he had was damp running down the walls. He just went on and on and was literally screaming at me. The only thing I could do was in the end to scream back at him equally loudly so that he could hear there was another human being on the end of the phone trying not to burst into tears. I just had to talk me down and talk him down until he ended up apologising. And there was me, just an individual sitting in my sitting room at home. It really shook me.

Pack all of that up together with the fact that I was dealing with some quite difficult stuff in the rest of my life, I actually got very ill. I was helping deliver the Transition Conference 2012 which was an awful lot of work anyway, and was a brilliant conference. I’ll never forget that High Street we built as long as I live. But I came away from that conference absolutely and completely depleted to the extent that I was diagnosed as clinically depressed, which is quite a frightening place to be. It is hugely down to the fact that a personality like mine can end up taking on too much because of the energy of yes and the seductiveness of wanting to say yes. Actually seeing change happen that you’ve been part of making happen is so good, yet because we didn’t have overt conversations about leadership or managing our personal resources – in the way that we’re trying to manage the planet’s resources – the result for me was burnout.

Also we don’t have a clear way of how you step back from a position that you’ve had in a group. It’s almost like the models aren’t there yet for how you renegotiate your relationship. The only thing I could do was actually to put down everything. Stop absolutely everything. I was so unwell for about a year I found even working really hard.

The group is still going of course (mercifully no one is indispensable!) and I am proud to have been part of it”.

Read more»

22 Jan 2016

UK Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne, said recently “we have to move to a new model of economic growth that is rooted in more investment, more savings and higher exports”. This growth-at-all-costs mantra runs through pretty much everything, yet at the same time, something fascinating is happening in pretty much every town and city in the country, indeed all around the world. A new model is emerging which eschews growth for its own sake, appreciates that businesses can get ‘big enough’, which favours local markets over export markets, and which doesn’t seek market domination, rather to inspire others to follow suit and become innovators and entrepreneurs themselves. Am I talking about the Degrowth movement? Or Transition? No. The craft beer movement.

In the conventional business world, being a business that isn’t that bothered about growth is a radical, counter-intuitive even, position to take. Yet Evin O’Riordain of London’s wonderful Kernel Brewery (see above) told a recent edition of ‘In Business’ on Radio 4:

“There isn’t an impetus here on our side at the moment to get any bigger. That would make more beer, and that would also make a lot more work, and it could be quite a stressful thing … this is our family and our community round here. It’d be so much preferable if there were lots of relatively small breweries around the place than having a big company that was dominant in a certain market”.

What, not planning for export markets in China? For exponential growth? For flotation on the stock market? Something fascinating is happening here, and that’s the subject of this post.

Welcome to the world of craft beer

What is craft beer? It’s a notoriously hard thing to nail down. For Wikipedia, it is basically any beer brewed in a small brewery. Yet a lot of that isn’t really craft beer, it may just as likely be a traditional ale. Craft beer tends to lend itself to a variation on the definition Justice Potter Stewart famously gave in the US when asked what pornography is, “I know it when I see it”.

For me, it represents an unprecedented explosion of flavours and tastes, of breweries vying not to sell the most beer into supermarkets, but to produce the finest beers they can imagine, to introduce people to new and delightful flavours. It opens the possibility that the range of beer on offer could be as, if not more, extraordinary and diverse than what we assume to be possible for wine. Indeed I would imagine that wine is already looking over its shoulder. It’s a breath of fresh, somewhat hoppy, air.

But that difficulty in defining craft beer is, for some, part of its strength and its charm. As Tony Naylor put it:

“The great thing about the craft upsurge is that it has made beer fans question everything. After years of lazy real ale dogma (cask beer is morally superior; lager is evil), flavour has become the paramount issue in beer. That is craft’s one guiding aim: the maximisation of flavour”.

What’s for sure is that the world’s taste buds, once they’ve been turned onto those flavours, are embracing them fast, and can never go back. Once you’ve drunk Beavertown Brewery’s ‘Gamma Ray’ (see below), or The Kernel’s ‘Table Beer’, for example, could you drink Heineken ever again?

Here come the take-overs

In the UK alone there are now 1,500 small breweries who now, between them, have a market share of about 7% and growing. In the US, the market share of craft beer is more like 12%. But last month it was announced that Camden Town Brewery, a leading craft brewery had just been bought by AB InBev, the company that create Budweiser among others (Budweiser has lost 16 million barrels between 2003 and 2013 due, in part, to the growth of craft beer), for £85 million. They join a growing list of craft breweries, such as Lagunitas, Goose Island, Meantime, Ballast Point, Golden Road and others, selling out to the large breweries.

In the UK alone there are now 1,500 small breweries who now, between them, have a market share of about 7% and growing. In the US, the market share of craft beer is more like 12%. But last month it was announced that Camden Town Brewery, a leading craft brewery had just been bought by AB InBev, the company that create Budweiser among others (Budweiser has lost 16 million barrels between 2003 and 2013 due, in part, to the growth of craft beer), for £85 million. They join a growing list of craft breweries, such as Lagunitas, Goose Island, Meantime, Ballast Point, Golden Road and others, selling out to the large breweries.

The idea that you can now buy ‘craft beer’ produced by a vast behemoth brewer feels like an interesting thing to reflect on here, a kind of fermented oxymoron. I have to declare an interest here. I am a director of a wonderful Totnes-based craft brewer, New Lion Brewery, which is deeply inspired by the craft beer explosion in the US, the UK and elsewhere. It’s something I love being a part of.

The Camden take-over raises some fascinating questions. In a passionate article reporting on it, Tony Naylor wrote:

…”for me, the idea that this corporate interference is benign, welcome or necessary, is naive. But, why? Why does Camden Town Brewery need to be ubiquitous in Britain, much less internationally? In any serious expansion of a brewery’s capacity, growth is talked about as if it is a self-justifying rationale. But – and this goes to the nub of the ethics around craft beer – beyond a certain point, growth is all about profit, not exciting beer.

No craft drinker worth their salty gose wants to see, as is increasingly the case, the same handful of corporate-backed craft beers everywhere. Indeed, rather than international craft brands, I would argue that what beer needs is more small local breweries, for both practical and ideological reasons. Beer begins to deteriorate as soon as it is shipped from the brewery, so drinking fresh, local beer is the ideal”.

The large, yet still independent, craft brewery BrewDog, who very publicly removed Camden Town Brewery ales from its pubs on hearing the take-over news, didn’t pull its punches in a blog it posted shortly afterwards:

“Let’s be honest, the intentions of these big companies are completely clear: they cut costs, they cut people, they cut corners and they take pride in doing so. Their God is market share and their stock market valuations; they act accordingly … however, it is by standing for everything that big beer is not that craft beer become so successful”.

Growth for whose sake?

Is growth, for its own sake, always a good thing? Is it a good thing that we are building many thousands of houses if they are poorly built, energy inefficient, lock us into high carbon lifestyles, are unaffordable, don’t create beautiful places where communities form, and lock people into a new housing debt bubble? Is more cheap food always a good thing when you take into account the impacts of creating it? Similarly, why is being able to buy Camden Town Brewery ales anywhere in the country a good thing?

As David Heinemeier Hansson, the founder of Basecamp put it in a speech that went viral online:

“Part of the problem seems to be that nobody these days is content to merely put their dent in the universe. No, they have to fucking own the universe. It’s not enough to be in the market, they have to dominate it. It’s not enough to serve customers, they have to capture them”.

On craft beer and ’emergent properties’

Just before Christmas, a piece appeared in a French newspaper (see right), based on an interview I had done while in Paris for COP21, entitled “The Transitioners say “cheers”” (I think), which began:

Just before Christmas, a piece appeared in a French newspaper (see right), based on an interview I had done while in Paris for COP21, entitled “The Transitioners say “cheers”” (I think), which began:

“Take a beer, a simple beer. With this, one can change the world. Or at least start”.

While I don’t actually recall saying that, and while it may feel like a bold and sweeping statement to make, I do think that the world of craft beer offers a fascinating window onto many of the wider debates emerging in this post COP21, “committed-to-1.5-degrees-on-paper-at-least-but-utterly-clueless-as-to-what-getting-there-would-actually-look-like” world. The brilliant Kevin Anderson of the Tyndall Centre, at the end of an interview recently posted on YouTube, said:

“We live in a complex world. Not just a complicated world, a complex world. Climate change is a very complex problem. The great thing about complexity is that it has emergent properties. Things come out that you would never anticipate, in fact you cannot anticipate them. We could see change emerge from different places, to give ourselves all some scope for thinking differently about the future”.

One of the places I see that potential, those “emergent properties”, is in the craft beer movement. Here we have a shift already underway towards a more small scale, local, independent, high quality, more flavourful, lower carbon, more delicious way of doing things, driven not by a political campaign, but by simply being better at what it does, and doing it with such passion and creativity. Yes, of course the failing giants that it is replacing will try to pick it up, mimic it, co-opt it, but when they do so it will crumble to dust in their hands, rather like the story of the Emperor who loved the Nightingale that sang outside his window, so he had it put in a cage at which point it stopped singing.

The craft beer movement has such huge potential to act as one of the butterflies flapping its wings so beloved by complexity thinkers. BrewDog state “it is by standing for everything that big beer is not that craft beer become so successful”. Indeed. But I think BrewDog are missing a trick too.

A Craft Beer Manifesto

Although various attempts at creating a Craft Beer Manifesto have met with varying results, I’d like here to suggest a few thoughts as to what might define the ground that the craft beer world could carve out for itself in reaction to the Camden Town Brewery news. It brings it closer to the REconomy/Transition approach, and could act as one of the powerful sparks for a thrilling shift, a shift you can already see happening in some craft breweries, but only a few.

It would be :

- Committed to supporting a new emergent local enterprise culture: this is the most important one for me. A brewery can back emergent local enterprises, creating beers with/for them (as we do at New Lion Brewery). It can support a Local Entrepreneur Forum, offer to make a brew for one of the participants, it can wear its commitment to a new local economy on its sleeve, act as a showcase for innovative new entrepreneurs, run collaborative events, create collaborative brews, and use its presence outside the town to tell those stories. I loved the story last week of Hackney Brewery’s new beer ‘Toast’, created with a local food waste charity and made using waste bread from the area.

- Rooted in place: where you are from matters. Celebrate the place, its culture, its history, its emerging new economy, its community. Wear it on your sleeve. Speaking to the BBC, Chris Knight of St. Austell Brewery said “localness is part of the romance, the connection with where it comes from and the association of that town, village, country, country: that’s all part of the story”.

- Aiming for 80/20%: applying the concept of economic localisation to a brewery is complex. Finding locally-sourced brewing equipment, bottles, ventilation systems and the other things you need when you set up can be very difficult, if not impossible, or prohibitively expensive. Much of the flavours that people associate with craft brewing comes from New Zealand and US hops. Yet just as some in the local food movement argue that 80% locally/UK produced and 20% imported feels like a realistic yet ambitious target, how might that apply to brewing? What local flavours could be experimented, and what local, vernacular (if you can apply that word to drink), as-yet-unimagined flavours might emerge?

- An artistic creation, not a commodity: craft brewing is about customers and the business owners seeing their brewers not as industrial chemists, but as artists, whose creativity should be nurtured and encouraged. It’s not about units shifted via striving for lowest common denominator tastes, but rather it’s about something less tangible, more focused on artistry.

- An education: I know very little about beer. I know what I like but would struggle to explain why. Everything I have learnt about beer has come through being interested in craft beer. It is a movement that wants to you care, wants you to be enthusiastic, wants you to be more knowledgeable, to understand the malts, the hops, the yeasts in what you are drinking. It’s not enough just that you buy it…

- Beer from here: if I buy a beer that claims to be from a particular place, I want to know it was brewed there, rather than, as is sometimes the case, under contract in the Netherlands or elsewhere. Keep the work local.

- Innovative and risk-taking: want to make a beer with Christmas cake in it? Or lavender? Or chilli? Suggesting such things would be a good way to get sacked at Heineken, but in the craft beer world, diversity is deeply treasured, and risk taking is where the rewards lie. Having said that, I did try a lavender beer once and it was quite horrible.

- Dedicated to broadening local support rather than export markets: although sales into national markets can be important for the bottom line and for establishing reputation, the more creative thinking is how to broaden local support, how to build a community around the business, how to displace the large brewers from local affections, how to sell direct to local people. On the Radio 4 ‘In Business’ programme mentioned above, Estelle Theobalds from Canopy Beer Company in Herne Hill, London, told that Radio 4 programme: “It’s about people looking for something that they can buy here, drink here, that they couldn’t get 20 miles away for example. I’d say 95% of the beer goes within a 4 mile radius of here”.

- Only contemplating selling out to their local community, and to no-one else: there are many different models, co-ops, member owned, a small group of investors and others. It would be great to have a stated principle that if the business feels the need to sell up, or bring in more investment, that it offers the community the first call on that, through a share option.

Final thoughts

We’re half the way there already. But a movement, an industry, which takes these ideas to heart, would be such a powerful catalyst. And we see the same latent but vast potential with bread, with vegetables, with meat, with finance and investment, with housing, with energy generation. The “emergent properties” and butterfly-flapping-its-wings potential of “standing for everything that big beer is not” is huge. Perhaps our call to arms could be the words of the 18th century French Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix: “life, life at all costs, life everywhere”. I’ll drink to that.

I’ll leave you with the words of David Heinemeier Hansson again:

“Examine and interrogate your motivations, reject the money if you dare, and startup something useful. A dent in the universe is plenty. Curb your ambition. Live happily ever after”.

Read more»

22 Jan 2016

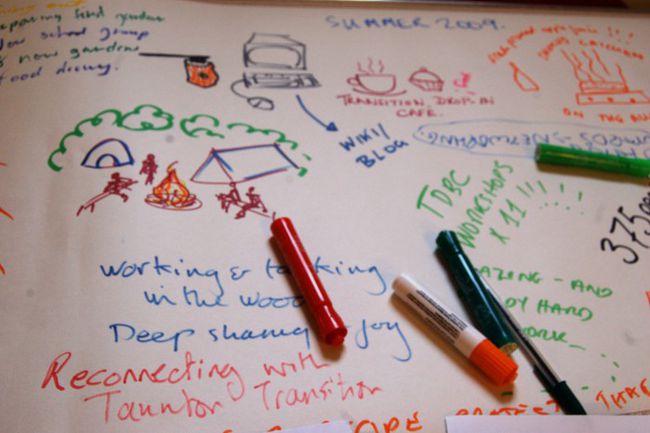

Oral histories have been something that has fascinated the Transition movement since the outset. The idea that the future can learn things from the past, and that a past with less oil wasn’t just the relentlessly miserable, dour, monochrome experience it can sometimes be portrayed as being, has been one that groups have explored in different ways. It was a delight therefore to be invited to an event last night hosted by Transition Town Kensal to Kilburn which was a celebration of a great oral histories project they had recently completed, ‘Old Stories for New Times: inspiration for sustainable living‘.

The exhibition presented stories and memories from older people in the Kilburn, Queens Park, Willesden and Kensal areas of the period from the 1940s to the 1960s. It captured their memories of making and sharing food, community life, transport and neighbourliness. Introducing the exhibition, they wrote:

“Our hope is that the younger generation and the community at large can learn from earlier lifestyles about practical skills, sharing and connecting with others, and the importance of keeping things local”.

The exhibition, in the local library, also included artefacts from the Brent Museum and Archives, such as a mangle and a copper, the washing machine of the time (give your washing machine a hug next time you see it).

What came through clearly in the stories was an unromanticised look at the past, but one that captured what was joyful and life-affirming from those times. The area suffered from poverty and overcrowding, and suffered from bomb damage during the war. We may imagine that immigrant communities who keep themselves to themselves is just a modern phenomenon, but one of the boards told the story of a Jewish man recalling a childhood spent mostly within his own community.

There were tales of make-do-and-mend; of the amazing levels of food produced locally at the time; of the West Indian immigrant who had to travel as far as Wapping to buy West Indian food; children spending whole days playing outside in the streets; one woman who used to make all her childrens’ clothes, including their school uniforms; families not having a car because “it wasn’t necessary”; of a vibrant high street economy. You could also listen to audio clips from some of the interviews. Beautifully done and delightfully presented.

The evening brought people together from the local community, some of those interviewed and people from Transitions Kensal to Kilburn, Ealing, Willsden and others. Viv from Willsden spoke about their projects, including their fruit harvesting project, and then Michael spoke about what had been happening in their group, who also do a very successful fruit tree harvesting project. Their approach is captured on a display board in the exhibition:

“We are a voluntary group with 1,000 local members that promotes sustainability and community, with practical projects open to all and support given to anyone with a project idea to make it happen”.

I then talked about the oral history work that I have been involved in in Totnes, which lead to the ‘Stories of our recent past’ section of the Totnes & District Energy Descent Action Plan, and the film “What the past can teach us about the future”. I talked about how an awareness of the past informs some of the projects underway, such as the Totnes Pound and the New Lion Brewery (with roots in the town’s historic Lion Brewery). Then the two women who had driven the ‘Old Stories for New Times’ project forward talked about it and what they felt they had got from it, and how the community had responded to it.

People then got into groups to discuss ideas they might have for projects that could be started which were inspired by the area’s past, which generated a lot of great ideas and possible future projects. The evening wrapped up with drinks and conversation, including NW6, a wine produced in the area by members of Transition Kensal to Kilburn, their ‘2014 Reserve’, the output of their fantastic Unthinkable Drinkable project. Hopefully we will feature this project in more depth here.

I’ve seen some great Transition-related oral history projects in the past, such as one I saw in Bristol a couple of years ago, but this one was one of the best: beautifully presented, and really capturing, in an unsentimental but deeply touching way, the lives of the generations before us, and how different their relationships were to food, transport, housing, their local economies and, perhaps most importantly, to each other.

En route to the talk, I visited, thanks to Michael Stuart, the now famous food garden on Kilburn Underground station. Its four raised bed planters, and espaliered apple tree, were captured and celebrated in the film ‘In Transition 2.0’, shown all over the world. Although now mostly dormant, it struck me that it was a garden that was creating, in its own way, a story that would be celebrated in the future, with its roots in the past so beautifully captured in the exhibition, one that, like all good stories, changes peoples’ sense of what’s possible.

I’d like to thank everyone at Transition K2K for a fascinating evening and for inviting me to be a part of it.

Read more»

14 Jan 2016

Book Review: The Urban Farmer: growing food for profit on leased and borrowed land. Curtis Stone. New Society Publishers (266pp).

In my visits to meet different Transition groups, I get to see lots of community gardens. Community gardens can be amazing spaces, places for communities to come together, to run events, to learn new skills, to taste good food and to see it growing. They clearly grow much more than just food. But what might it look like if they were also designed to maximise the productive use and economic potential of the space available? If the intention was to create as much employment as possible, how different would they be? If they were reimagined to act as a spark for an entrepreneurial, REconomy-based approach?

We could allow ourselves to dream how it might be if that approach extended beyond community gardens, and large swathes of land in our towns and cities hosted beautiful, diverse, abundant gardens growing good food and viable incomes. Curtis Stone’s brilliant new book ‘The Urban Farmer’, is one of the most important contributions to Transition thinking over the last 10 years, and sets out in great depth and detail what that could look like. And he knows because he’s done it. Here’s the promotional video for the book which gives you a sense of it:

The Urban Farmer is simultaneously deeply visionary and immensely practical, always a heady brew. “What if we could repurpose the suburbs to be the new frontier of localisation?” writes Stone. “What if all of these new suburban streets turned into areas for transition, reeducation and abundance? I believe this is not only a possibility but an inevitability”.

As he points out, there is nothing new about growing food in cities, and nothing new about doing so commercially. For example, Paris was home to incredibly sophisticated fruit growing systems, and to market gardens who pioneered a system now referred to as “French Intensive”, which, until the 1920s, covered 6% of the land within the city limits. As Eliot Coleman put it in “The Winter Harvest Handbook”:

“The Paris market garden of the nineteenth century measured on average 4000-8000 m2. A master gardener gave this advice: “Always choose the smallest plot of land as possible, but grow it exceptionally well.” Another market gardener of the time described their profession as “the goldsmiths of the ground.””

Well, that advice is much the same as Stone would give today. Growing food in cities, in many ways, makes more sense than growing it on a farm. You are closer to your market, and have the opportunity to build a closer relationship to them, your start-up and overhead costs are lower, you have better growing conditions with more favourable microclimates, less pests and weeds, better access to water. ‘The Urban Farmer’ takes you through everything you could want to know about becoming an urban farmer.

“It is important”, he writes, “to understand that urban farmers cannot and should not try to grow everything”. There is no point, for example, growing grains, or potatoes: it makes far more sense to focus on short greens with short shelf lives, which don’t benefit from long distance travel, or which have a high yield per square foot. So Stone sets out in the book how to find suitable sites (private gardens, waste land, Council land), suggesting that poring over Google maps of the place you live might be a good place to start. He takes you through how to get the soil checked, start a business, develop your business plan and marketing, how to design your site for maximum output, what tools you’ll need, how to extend the season at low cost, what crops to grow, how to harvest and different models for selling.

Perhaps the most inspiring, and powerful, part of the book is his “start-up farm models”. Here he sets out 5 different business models on different scales, what kind of initial investment you’d need and what kinds of return you might expect. You could start on a quarter of an acre or smaller, or go a bit bigger. For each he sets out the kinds of crops that could work well, and the kinds of profits you might expect.

He captures a spirit emerging in all kinds of different settings. The craft brewing movement takes a similar approach, as Tony Naylor argues in a recent article in The Guardian:

“Rather than international craft brands, I would argue that what beer needs is more small local breweries, for both practical and ideological reasons. Beer begins to deteriorate as soon as it is shipped from the brewery, so drinking fresh, local beer is the ideal“.

Scaling up the approach Stone sets out here has the potential to reimagine our towns and cities. We can get a sense of what that might look like by looking to Tordmorden, to Detroit, and to other places, as the film ‘Demain‘ so beautifully captures. An economy that values taste, innovation, relationship, place, is already here, and is growing fast.

One of my dreams when we started the Transition movement was that we might reach a point where urban market gardeners, people growing mushrooms in old office blocks, craft brewers, people baking amazing bread in old industrial units, would be the coolest people around. Young people would yearn to emulate them. At the end of the book he writes:

“Let’s live a new definition of what it means to be a farmer: one who is at the root of the community by serving the needs of those in it. Farmers connect people to where their food comes from and empower others to start growing food themselves. Farmers can turn derelict areas into beautiful and productive farms that are flagship examples of local food resilience”

I was sent an early version of this book, and wrote an endorsement for the cover. I wrote:

“If I were 18 again and given this book, it would put a fire in my belly and set me on a career path that is cutting edge, deeply entrepreneurial and profoundly responsible. The Urban Farmer deserves to be a best-seller”.

Read it, and dream small (in a good way). Vital stuff.

More information, and order your copy here.

Read more»

13 Jan 2016

Chris Johnstone is an old friend of this blog, a resilience specialist and writer, author of ‘Active Hope’ and ‘Find your Power’, who is now living in the north-east of Scotland. One is his areas of speciality is balance and burnout, so we felt like the ideal person to catch up with. We started by asking what, for him, is burnout?

“Rather than a definition, I prefer an image. When I think of burnout, I think of the image of a field of wheat that has been over-farmed for years, to the point where soil declines and the field no longer grows very much. We see this happening all around our world where once-fertile areas have decline of topsoil to the point where they no longer produce the same kind of yield. If you think of that in human terms, you can think of somebody who used to be enthusiastic and productive but gets to the point where they feel used up. Where they’re no longer able to offer so much, but importantly their quality of life, their experience of life also really declines. It’s like life goes sour.

Another image I have is of a tube of toothpaste that has been completely used up and every last drop of it has been squeezed out. It’s used up and there’s nothing very much there left.

Burnout isn’t something that you tend to hear about so much in the Women’s Institute or football supporters’ clubs – while it affects many people in stressful work contexts, it does seem to be something activists and change-makers are particularly prone to. Why is that, do you think?

There’s a saying that “in order to burn out, you need to first be on fire”. Burnout is a risk where people have a strong sense of passion behind what they do. If somebody’s very committed to their work, there is research which shows that the people who are most at risk of burnout tend to be those who are most conscientious and sensitive. If you didn’t care about what you were doing, if it wasn’t so important to you, you’d be at less risk of burnout.

There’s a saying that “in order to burn out, you need to first be on fire”. Burnout is a risk where people have a strong sense of passion behind what they do. If somebody’s very committed to their work, there is research which shows that the people who are most at risk of burnout tend to be those who are most conscientious and sensitive. If you didn’t care about what you were doing, if it wasn’t so important to you, you’d be at less risk of burnout.

But also it’s a word that’s going to be talked about more because research is showing very clearly the whole thing about aiming for industrial growth is that people are being squeezed harder and harder in their workplaces. Stress is on the increase, and it’s already one of the major causes of time off work through sickness: stress, anxiety and depression. We live in a more driven society where the casualty rate is going up.

Very often, the organisations who argue that we need a new way of doing things, a new economy and so on, as organisations can often end up being driven and working in much the same way, having the same kind of work culture, as what they’re trying to replace…

There’s an issue here because you look out at the world and there’s so much that needs to be done. We really are in such a dire state in so many ways that you can have that sense of urgency driving us harder and harder. Also for people whose work is basically about service work, there’s often a resource issue. The demand is high but the resources supporting their work are often inadequate. So that puts people under a great deal of strain.

One of the questions that Sophy Banks raised in the editorial piece that she wrote for this theme was “what might it look like if the culture of Transition as a movement, if the DNA that people who, wherever they are in the world pick up Transition and start to work with it meant that there was no burnout” What would that look like, do you think?

First of all, I love Sophy Bank’s piece and point people towards that. It’s a very important piece of work that you and her have done in just opening up the conversation around this area. I think you’d recognise an organisation that had really dealt with burnout if as well as working for change out there in the world, one of the areas of its attention was also what I call “the middle bit of change”. The middle bit of change is the first bit of change is becoming aware of the problem, the third bit of change is having the action response to that. The middle bit of change is everything that happens between awareness and action.

It includes things like our levels of enthusiasm; our levels of energy; whether we even want to look at an issue; if we pay attention to that middle bit of change and we see that that’s part of the work of activism, that would be the kind of thing you’d see in an organisation or a movement that had really come to deal with burnout, where there wasn’t any burnout. If we really paid attention to that, we’d pay attention to things like enthusiasm.

I see enthusiasm as being like topsoil. If you have high levels of enthusiasm, out of that the best yields tend to grow. So if an organisation paid attention to enthusiasm, then they’d look at things like – do people feel enthusiastic about coming to our meetings. Some meetings are boring, they’re heart-sink areas. But if we really paid attention to – what would make this a meeting that people would want to come along to.

I think there are some great examples out there. I’ve given some talks and run some workshops for Sustainable Frome and I was very impressed with them. They had a problem where they had meetings that weren’t that well attended. One of the things they did was they said “let’s meet for a shared meal before we have the meeting, if we’re going to have a film or something, let’s meet first, we all bring along some food and we share it”.

It changed the quality of their meeting from something that people think “oh, I should go” to something that people wanted to go to, that they looked forward to. That’s one of the things, if we can make our meetings things that people look forward to coming to, that will be the kind of thing that will go a long way to making burnout less likely.

I remember Peter Macfadyen in Frome who was one of the people in the group who became the Mayor. He said that when he became the Mayor he would always bake cookies to take along to the meeting and how it changed the quality of the meeting: starting out with some biscuits he’d made before the meeting.

I love that phrase you just used “changed the quality of the meeting.” There’s content in terms of what do we do, but there’s also process which is how do we do it. How do we change the quality of our meetings? It’s seeing that how we do things is as important as what we do; that we live in an economy that’s very focused on product, very focused on what comes out the end of an assembly line. That can also be true of activists. We can judge what we do by the end result. Also we say – how can we do it? Can we do it in a way that is nourishing? Can we do it in a way that is attractive? When we start asking those questions, when we really look at the quality of our meetings, it really changes things.

Sophy’s blog included the quote “burnout is the dirty secret of the environmental movement.” After COP21 in Paris there will no doubt be a lot of burnout, given the expectations and the intensity of those 2 weeks. What advice would you have for the wider climate movement post COP21 with regards to burnout?

One of the first things to say is a lot of this work for our world is hard and there are big disappointments along the way. I draw inspiration from historic examples and particularly the campaign for the abolition of the slave trade. People might know that it was just a dozen or so people who met in an old print shop in London one evening. Out of that, many other things that followed, a movement grew.

What’s less known is that there were huge dips and disappointments in that campaign. There was a period where there were much harsher laws where the campaign closed its office for about seven years. They stopped their meetings and it looked like all was lost. And yet turnings can happen. This is where – one of the things for me is I draw inspiration from adventure stories.

What’s less known is that there were huge dips and disappointments in that campaign. There was a period where there were much harsher laws where the campaign closed its office for about seven years. They stopped their meetings and it looked like all was lost. And yet turnings can happen. This is where – one of the things for me is I draw inspiration from adventure stories.

Adventure stories often have what I call their ‘Chapter 7’ moments. Usually by the middle of a book, certainly by chapter 7, things have gone hopelessly wrong and it all seems lost. But also the story is about turning and change and it’s looking at how we make that more likely.

One of the strengths or qualities that will make a turning or change more likely is resilience. This is why I have learnt so much from you, Rob. You’ve built a whole movement around taking resilience seriously. Part of resilience is community resilience and societal resilience, but also part of resilience is personal resilience. I’ve made this a big piece of my life’s work, looking at what helps us keep going.

I call it finding the ‘up slope’ of a dip. When we get down, how do we climb back out again? We need to see this as centre stage for activism. It’s not some fringe meeting that might happen now and again for people who are touchy-feely types. We need to bring this centre stage.

It is also centrally about an ethic of sustainability. An ethic of sustainability is about looking through a larger lens in time, inhabiting a larger, wider timescape. If a timescape is a period of time that we give our attention to, often it can be quite a narrow space. It can be the period of now plus or minus a few years. If we see this working for our world stuff as something that we need to do for all our lives, it’s a marathon not a sprint, or if it is a sprint it needs to be what they call interval training where you push hard and then you pause and renew.

You push hard and then you pause and renew. If we’re seeing that we’ve got a long distance to go, we need to look at how we find a sustainable pace and how we nourish ourselves to keep going.

Read more»