Archive for “Originally posted on Transition Network” category

Showing results 46 - 50 of 383 for the category: Originally posted on Transition Network.

17 Feb 2016

In a final interview before she left Transition Network to take on new challenges, I sat down with Sophy Banks to talk about burnout and balance, our current theme. I started out by asking her what, for her, is meant by the term. You can hear the interview in full as a downloadable podcast (here), or read the edited transcript (below):

“Burnout, I think, applies at every level of scale. There’s clearly a personal kind of burnout that I’ve been close to and know many people that have been to that place where they’ve been out of balance or they’ve been giving so much or working so hard over an extended period that actually their health is very severely compromised by it. At the end point, it always ends up affecting our health physically, but possibly mentally as well.

People are exhausted, where their immune systems are trashed and they’re in a very long process of recovery to come back to full health, if they ever do. The long-term consequences is part of the characteristic of burnout.

Is there an example of burnout in your own life that you would like to share, or that is instructive?

Yes. I’d like to talk about Transition Town Totnes where I think we did a really good job with issues around energy and burnout. I remember that second Core Group meeting, really in the early days. You and Naresh had been doing those launch events and open spaces. You had seeded groups, and some of the groups had come around spontaneously. You called that first meeting in February 2007. I remember talking with Hilary Prentice, we were the two Heart and Soul founders. It was probably her idea, but we decided at the next meeting we were going to do a check-in around energy levels.

This was our second meeting and I think it’s really interesting, when you look back at the minutes, there it is. We had a go-round about – what are you giving, what are you getting from being part of this project, and how sustainable are you for the next one, three or six months? There were six or seven of us each focalising a group that knew they were putting on lots of events, and everyone knew they could probably last six months but not longer. Everybody! We were all so excited and wanted to give so much.

I remember at that meeting we went through that thing – what are we going to do about this? This clearly isn’t sustainable in the long term. We said either we have to get paid support, or we have to really scale back what we’re doing. So we said let’s try the first option, and if we can’t we’ll have to consider the second. In a couple of months, you’d managed to find some funding to get a paid admin support person. So for me, that’s a really good story of a group doing a really good job. I think it’s interesting that a year later we set up the Mentoring Project to give one-to-one support for the personal aspects of “how are you doing”, and reflection. I know there have been people that have been tired in the Totnes project, but as a project it has had very little real burnout.

In this story, eventually, the corrective loop worked, and I’ve met many people and seen many groups where the corrective loop hasn’t worked and resulted in people with long-term health problems from burnout in Transition and in many, many other movements for positive change, and what a paradox that is. I’ve heard people on trainings say, who’ve been in the environmental movement for 30-40 years, that burnout is ‘the dirty secret of the environmental movement’. That people used to burn out in those organisations from a relentless work schedule and culture, and they would just disappear and nobody would even ask about them. They would just disappear from sight. And how upsetting that is that these very dedicated people would just sink and not be seen again, and be left on their own to deal with the consequences of that.

One of the things that’s central to both of those stories is the person, yourself and/or Hilary, the people who say “I think we need to look at this in a bit of a different way”, to be the person to point out the elephant in the corner. There will be people listening to this I’m sure who are in groups who recognise the same things that you’re talking about, the same symptoms you talked about. What advice would you give to people in that position? To be their burnout whistleblower, the person who names it. What advice would you give to them?

I’ve met many people that have tried to put a check-in at the start of a meeting, where people go – that’s too touchy feely, or – why do we need to do that, or – we don’t have time…

…I remember Sharon Astyk wrote a piece where she even felt that putting chairs in a circle somehow smacked of a cult…

That’s right. There are extraordinary levels of defence against very simple pieces of good human technology in our culture. That’s the landscape that we’re in. One of the things is to have the confidence to put ‘How do we work as a group?’ as an agenda item; that people feel confident in all kinds of other things in that that are about tasks, but actually to say – I want this group to spend 20 minutes reflecting on how we want to work as a group, and to start opening that up as a normal topic of conversation in a group.

One of the frames that I sometimes use is – do we want this to be a group that cares about people? And if so we need to know how each other is. How can I care about you if I just don’t know if you’re ok or not? I like that parallel, if you meet someone in the street, you wouldn’t just go “what are you doing, how are you getting on with it, where are you on your to do list?”

The first thing you’d say is “how are you?” You may or may not want the short version of that, but you know that’s how we greet each other because it puts us in a frame of caring. I think if we can root it in that frame of being a place where we’re all about caring in Transition: we care for the planet, we care for our communities, our work in Transition as an embodiment of that, and actually we need to bring that right into this group where we care about each other and we know and we understand the principle.

When we have connected, trusting relationships, that’s when we have a group that can do wonderful things. So there’s not a competition between the time we spend staying sustainable, welcoming new people, and getting on with the doing. They absolutely complement each other.

I do think there is just a frame. It’s like there’s a frame inside us that has this strange belief that spending time on our relationships is a waste of time. As soon as we shine a spotlight on it in Transition it shifts, we just have to draw attention to it in a way that doesn’t trigger too much of a defence. I think how you stand for that – this is what I see, this is my agenda item, this is what I want the group to pay attention to, you do that with a gentle confidence, not an aggressive “this group’s terrible” but to do it with kindness, bringing the qualities that you really want the group to have. It makes it easier for people to relax into that conversation if it’s a stretch for them.

As soon as we’re outside our organisational frame, in to reminding ourselves how we are with our friends, that it really helps us find that part of ourselves that finds it completely normal to check how we’re doing.

You used the word ‘technology’ quite a few times in terms of social technology or group technology. If we think of Transition as being a social technology, a set of tools, resources and things, what would that technology look like or what would need to be different about it so that it could be designed from the outset so that burnout wouldn’t happen. Is it possible that we could design a movement which in its very design, designed out burnout? What would it look like? Is this the first organisation to have asked that question? I’ve never encountered it anywhere else before.

I think the powerful question is, is in any organisation or movement, “what’s the shadow for us?” “What’s the thing that we create unconsciously that’s destructive or harmful, and how are we like the thing we’re trying to change?”

I think the powerful question is, is in any organisation or movement, “what’s the shadow for us?” “What’s the thing that we create unconsciously that’s destructive or harmful, and how are we like the thing we’re trying to change?”

One of my teachers once said to me “one way to enquire into that is to look at your aspirations as an organisation, what’s your mission, and imagine the opposite of that, and then ask the question, how are we doing that.” So if Transition is all about exclusion, where are we exclusive. It’s quite easy to see there are lots of people who don’t find a place in Transition. If we’re all about healing a culture of manic activity and burning out the planet, where are we creating burnout ourselves. So that, I think is a really powerful question for any group or any organisation to ask.

It’s really important what the leaders do, and if the leaders don’t have good practices where they model balance themselves, if people see the leaders constantly doing and doing and doing and they don’t take time out and don’t reflect deeply and don’t get support, their groups and their movement will be created in their image very strongly.

It’s difficult as a leader to imagine how much impact you have around that. I have experienced that – it’s hard for me to even think of myself as a leader because it’s not my self-image, but I see that I have had a lot of impact. I think at those moments when the symptoms are starting to show, the response of the leaders is really critical. If they pay attention to it and give it value, that’s ¾ of the system. But if they’re ignoring it, dismissing it, haven’t got time for it, actually it’s very difficult for people with much less power or rank in the group to challenge the culture. In some groups there are strong leaders, in others it’s much more shared, so that can be very different.

But there are things that we can build into how our groups work. Nick Osborne’s done lots of stuff on effective groups, and I have this really simple three aspects of group life, one of which is task, and the other is all the structures that we need, the agreements, the roles, the clarity about our purpose. If we don’t have those it’s exhausting because nobody is on the same page together.

The third, which is the group that tends to get marginalised the most is about relationships, about caring, about building trust, about deepening into…I think it’s really interesting to ask – what is Transition, why are we so strongly called to it? You find really, really deep motivations about our love for our children, our profound sense of responsibility for life on Earth, the core of who we are as human beings and our identity. It’s all woven into why we do Transition.

When we open space up to hear each other about that, all of those petty irritations about “I always make the tea” disappear in this sense of being with human beings that share a deep love of life and beauty and this incredible natural world that we all live on and hold. So that bit about relationships I think is important.

There are some great statistics that help with burnout, like groups that spent 25% of their time on process, on how they work; on the how rather than the what are the most successful groups in every aspect; the most productive groups as well as the most long lasting.

Another antidote to burnout is having this culture, that a lot of people hear me talking about, of appreciation and celebration. If we don’t constantly keep reinforcing for ourselves this sense that what we are doing makes a difference, that each person’s contribution is valued, that we’re grateful for the incredible things that we have in these times, that’s also a thing that gradually depletes people. I think it’s interesting to think that sometimes people come to groups just to be seen and valued. They will give a tremendous amount if they get that back.

Read more»

12 Feb 2016

The spirit behind Transition, that invitation for a community to come together to reimagine and rebuild itself, takes many forms, not all of them choose to use the label Transition, and some, like the story told in this book, emerged before Transition but very much sees itself as being a Transition initiative in spirit. Earth builder, ecological designer, author, educator and occasional Transition Culture contributor Robert Alcock has just published a book that gives a powerful taste of one manifestation of that spirit, set in the city of Bilbao, Spain.

The book is written in three languages, English, Spanish and the language indigenous to the place where our story takes place, Basque. It tells the story of a forgotten barrio in the city, a small neighbourhood, “like a village in the city”, that had once been quite grand but which the city had largely forgotten about. It was a neighbourhood which he describes as “low-rent and bohemian, but despite appearances, not really dangerous.”

The neighbourhood was situated along the river, and had once been a vibrant dockland area. Now it still contained a few businesses, but also “the remnants of an industrial past that had never been tidied up”. Once it had been home to market gardens which made the most of the alluvial silt, but in the 1950s Franco decreed that Spain needed a huge expansion of industry, and the site became an Enterprise Zone. Factories arrived, canals were dug, and the area became known as Zorrozaurre. However, 30 years later, the economy collapsed, attention turned elsewhere, but 400 residents remained. By the year 2000, Bilbao was buzzing again, this time as a centre for design and fashion and culture, and developers started eyeing Zorrozaurre with interest.

It was into this somewhat down-at-heel setting that Robert and his partner arrived and set up home, initially getting involved in the creation of a ‘micro-garden’ on the waterside, which which gave people a sense of shared ownership of a common space for the first time.

It was into this somewhat down-at-heel setting that Robert and his partner arrived and set up home, initially getting involved in the creation of a ‘micro-garden’ on the waterside, which which gave people a sense of shared ownership of a common space for the first time.

As he puts it, “at least now we had something to squabble about”. The place also had its own social world, of parades, festivals, and a lively local graffiti art scene into which Robert immersed himself.

But at this point, the developers started to move in, appointing a superstar architect to “wave her magic wand and conjure up a sparkling Master Plan for the peninsula”. The rest of the book tells the story of how the community, in all its cantankerous, diverse, argumentative yet also really rather wonderful glory, responded to this. I won’t tell you any more as it’s a story you need to read and enjoy yourself. It’s a fascinating and heartening tale of the power we have but spend so much time convincing ourselves actually lies elsewhere, and asks the question “what if ‘meanwhile’ became a permanent condition?”.

It’s a quick read, beautifully illustrated, and can be order directly from Robert’s own website here.

Read more»

9 Feb 2016

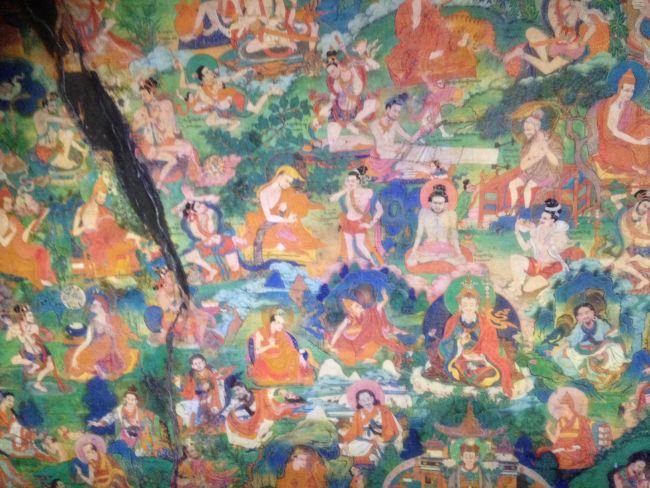

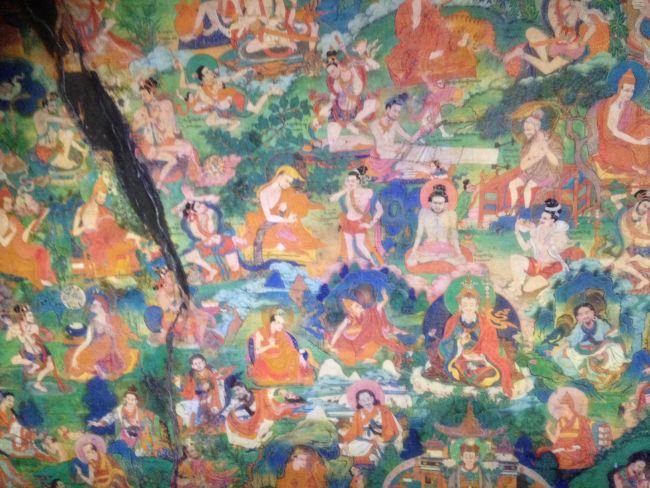

Last week I visited an amazing exhibition at the Wellcome Collection in London called The Secret Temple: Body, Mind and Meditation in Tantric Buddhism, (it’s on until February 28th). The exhibition is a celebration of the Lukhang, a temple close to Lhasa’s Potala Palace which was conceived by the fifth Dalai Lama and built by the sixth, a private meditation temple which showcased, in its extraordinary murals, ancient, esoteric and once secret practices central to tantric Tibetan Buddhism.

To step from the busy streets of the Euston Road into the quiet of the gallery felt, in itself, like stepping into a temple. The first thing you see is a beautiful film about the Lukhang. The story goes that during the construction of the Potala, the fifth Dalai Lama dreamt that the local spirits or nagas were upset by the amount of earth moving the construction necessitated, and so he promised to build a temple in a lake to pacify them. Here is the film that greets you when you first arrive:

In the end he died before work could start, the sixth Dalai Lama finally building it. The Lukhang was only reachable until recently by boat, and it features some of the most exquisite Tibetan art and wall painting. The current Dalai Lama, it is revealed at one point in the exhibition, never actually got to set foot inside the Lukhang, as he had to flee Tibet before he got the opportunity, but remembered as a child looking longingly at its roof from the windows of the Potala and wondering what it was like inside.

The exhibition uses the temple as the starting off place for an exploration of Tibetan Buddhist yogic and meditational practice, and the remarkable system they developed for creating physical and mental wellbeing. Beautiful statues, paintings, archive footage of lama dances in a monastery near Mount Everest filmed in the 1930s, along with commentaries from a Tibetan lama that adds insight and depth to what you’re seeing. One section takes you into the imagery of Tibetan tantra, of wrathful deities, flaming protector deities, and lots of skulls.

The centrepiece of the exhibition is three life-sized digital versions of murals from inside the Lukhang. Absolutely beautiful, lit from behind, in a darkened room, they capture an incredible civilisation and practices designed to develop and deepen compassion which were developed over many centuries.

While the exhibition itself was beautiful, fascinating and an absorbing immersion in an extraordinary, and much-endangered culture, the highlight for me came at the end. The final room featured a large screen showing a video which featured a couple of academics from leading universities both in the UK and in the US, the Tibetan lama whose commentaries had accompanied us through the exhibition, and the head teacher of a school in the UK which teaches mindfulness throughout its curriculum.

In the video, they discuss compassion, and the emerging body of science around it. They talk about how, in neuroscience, in the study of neuroplasticity, the practice of mindfulness and compassion has been shown to have huge benefits. One researcher talked about taking a random sample of people, teaching them a simple compassion practice which they then did for two weeks at which point they were then tested again, the results being that many benefits were discovered. Research now shows that being more compassionate results in us being happier, more attractive (“kindness” is the key quality people look for on dating sites), boosts our health and longevity, spreads to those around us, leads to more pro-environmental behaviour and leads to our feeling like we have more time in our lives. The head teacher talked about the amazing impacts she noted mindfulness practice having on kids at her school, on their school performance, confidence, and ability to be still and quiet.

At this point I was struck by the thought that here we had a culture that isolated itself from the rest of the world and spent over 1,000 years as a Silicon Valley research laboratory into the science of compassion, a Hadron Collider for mindfulness. Its whole culture was repurposed from being the region’s most feared warrior nations to being a nation of monks, nuns, temples, deep reflection and study.

I thought about how, in our current obsession with economic growth, so much is made of how important it is for businesses to be exporting (the UK seeks to double its exports by 2020), to be seeking markets elsewhere. While the UK, for example, exports some good things: culture; design; music; films; it also exports food that could just as easily have been consumed here, as well as torture equipment; tanks; missiles; bombs; money to off-shore tax havens.

I sometimes remark that Transition may turn out to have been the key export of Totnes when history looks back at these times. As I walked back out on to the Euston Road and headed for the Tube, I wondered how different a world we would have if we, like the Tibetans, measured our success in the world not by the amount of stuff we export, but rather by the qualities and the ideas that we export. By choosing to live more simply, more kindly, more compassionately, while such an approach would inevitably reduce our physical exports, we need to bear in mind that we would end up exporting something far more important, long-lasting and needed. A national Transition would be remarkable demonstration of compassionate action, and would also turn out to be our finest export.

Read more»

4 Feb 2016

The film ‘Demain’ (‘Tomorrow’) is proving to be one of the most remarkable catalysts for Transition and other bottom-up approaches that has ever been made. I recently saw it described by a friend of mine as “‘March of the Penguins’ for localists”. Mention of it often pops up in emails from people who have seen it. One recently said “Demain is working really well in France, it is a crazy phenomenon, never a documentary has touched so many people in France”. Another friend rang me from outside the screening he had just taken his son to in Paris, so thrilled by it he had to call me straight away to say how wonderful it was.

Demain in France

The film, created by Cyril Dion and Melanie Laurent, was premiered in Paris during COP21, and has since been seen by 560,000 people in France alone. It is now into the 6th week since its release, and this week has been the best week yet for the film, seeing a 29% increase in the number of people going to see it. This week it is on in 293 cinemas in France (see the list here). It is currently number 15 in the box office charts and has 103,000 followers on Facebook.

It has been nominated for a Cesar award (the French equivalent of the Oscars) for ‘Best Documentary’. Cyril and Melanie have appeared on all manner of TV chat shows (such as the one below) and the level of media coverage has been amazing. Its inspiring message has really hit a chord with people. As Cyril told me, “we are receiving every day messages from people launching projects or using the movie to support current initiatives”.

A review in Le Monde said described the film as “a phenomenon of society”. It added:

“In a France darkened by crisis and terrorism, this documentary is a ‘breath of hope’ … (it) presents the spectators with people who are not in the light, but who create, invent, and are preparing for the future. It takes them out of the impasse”.

Another, in La Vie, wrote that “this was a rare thing: the audience actually spoke to each other, before and after the movie! Indeed, many of them were there for their second or third viewing of the film”.

Demain in Belgium

It launched in Belgium a couple of weeks ago, and most of the screenings have sold out, with 13,000 people seeing it in its first week. Screenings have proved a huge boost for Belgian Transition groups. The Belgian equivalent of the Radio Times, their TV listings magazine, dedicated 7 pages to it, half of those to stories of what Transition groups are doing in Belgium. The Belgian Hub, Réseau Transition, asked groups for their stories of the impact the film is having. Here is what some of them said. Elisabeth (Liz) Gruié wrote:

“I live in Liège and watching Demain crystallised my appetite to support the ‘green’ cause and more specifically to get involved into sustainable and local projects… I contacted the team at Liège en Transition to see where I could be involved. I bought two shares in Les Compagnons de la Terre and I am now part of their communication team. Finally I invested into a Cooperative Bank and will open an account there instead of going for the brick-and-mortar banks. I started to buy and use the local currency (‘Le Valeureux’) and as a future switch to renewable energies I am now looking into Enercop to replace my local provider. So many changes indeed!”

Catherine Etterbeek wrote, “What strikes me is rather the impact on the people around me, who are external to the Transition”. David from Etterbeek in Transition wrote, “overall I think it reinforced the image that I have with my relatives and acquaintances (who begin to consult me on some issues) and I think it will pay off in the long term!”

Carolina from Ixelles Transition wrote:

“We welcomed new members since the film’s release. We noticed such enthusiasm around us that we decided to organize an event around the ‘day after tomorrow. ” This is called “Tomorrow, I promise” and will take place at the end of the month. Difficult to assess the impact before that date, but we’re getting close to 100 participants on Facebook + some very positive feedback about the organization of this event. It’s been a while that we did not have noticed such enthusiasm. We therefore expect a coffee debate on five themes of the film and will explore new ways to offer people to engage effectively”.

Demain in Switzerland and beyond

It recently also launched in French-speaking Switzerland, where it is Number 2 at the box office, with 21,000 viewers so far and momentum growing all the time! So what next? Distribution rights are currently being negotiated for other countries. We will keep you posted on news. The announcement about the Cesar awards is made on February 26th. In the meantime, if you haven’t already seen it, here is the trailer.

Read more»

3 Feb 2016

Back in May last year, I read in the papers, they found Anne Leitrim dead in her flat in Bournemouth. Her body had been there six years. Tragic, I thought, inconceivable. Then I asked myself just how many neighbours I have who would come knocking on my door. And the answer was zero. A few weeks later I tried to greet a woman I half recognised heading towards me on my street. “I know you,” she replied. “You’re the guy on his mobile phone all the time.”

The next month, on the cricket pitch, I tried to smack the ball into a lake, missed it and severed my Achilles tendon. The big lesson is never exercise. But it was a fantastic chance to read (which I didn’t take, I watched Breaking Bad). But I did start to walk, all over the ex-orchard turned into concrete that is Kiburn. Over the weeks, as I hobbled around the area on crutches, I saw bunches of wild grapes start to ripen, from green to purple to black.

One day, in the park, I got overtaken by an old Italian man. “Excuse me,” I said to him on impulse, “but do you know how to make wine?” He stopped, silver-haired, back ramrod straight. “The soles of my feet,” he replied, “are still red from making wine as a boy”. We were off. We were going turn Brent into the Napa Valley of the North.

The old man’s name is Paulo Santini. He is 84. He turns out to live 2 doors down. He last made wine 55 years ago in his village in Emilio Romagna. That summer he made it again, leading a crew that, over the months, has involved some 100 of us from the area. There was Nicola, a 70-year-old Italian former lorry driver with something of an eye for the ladies, Jane from Alabama, John Joe Moloney, a fruit-picking Irish engineer with his girlfriend, Vanessa, from Venezuela (think Sophia Loren on a retractable ladder in Willdesden), Rei’Anna and Roselyn overseeing quality control in Sunday finest; and two lynchpins of the Transition Town movement in our area, the two people who really made it happen, John Smith from three doors down, and George Latham.

Over summer weekends we picked the grapes as they ripened, knocking on doors and asking bewildered owners to let us in with our ladders. No-one said no. In total we picked 200kg (440lb) of wild vine Fragolino grapes. Then we trod them, out on my front stoop, plunging waist deep into the mash of grapes, our legs blood-red as we emerged from the barrel. We trampled barefoot, washing each other’s feet, because human skin can coax the peel off a grape better than any machine. My legs still itch from the tannin.

I used my daughters as human grape crushers. “This is more fun,” my eldest said, head barely visible, “than shopping at Zara.” “Do you have any scissors?” another woman who had travelled over from Bermondsey asked, then she cut off her black skinny jeans off at the thigh to join us in the barrel. I have still got the bottoms. “Vendemmia –” said Paolo, “this is the harvest.”

Unthinkable Drinkable Brent is the name of our project. Of course we were in it for the booze. We had a dream of 150 bottles. But it was about something else as well. Could we rediscover some lost skills? Could we reconnect with each other? Could we live on a street where none of us, me included, would die unnoticed? Where we would be more than someone passing on a mobile phone?

Some 200 bottles we made in the first year, and it is indeed borderline undrinkable; Brent Crude is its local appellation. The Archbishop of Canterbury has a bottle in Lambeth Palace, reserved, it is alleged, for unrepentant sinners. The bottles have all gone, before you come beating on our door, but next years crop (2015b – we had apparently got the year wrong the year before), looks like a bumper, with no less than 250 more bottles of unthinkable red on its way, and to wash it down, our new line, Transition Plum Slivovitz – harvested from the plum tree outside Kilburn Police Station…

Leo Johnson is one of the cofounders of Unthinkable Drinkable Brent and a member of the core team for Transition Kensal to Kilburn. He is the author of “Turnaround Challenge: business & the city of the future” and co-presents the radio four programme “Futureproofing”.

Read more»

I think the powerful question is, is in any organisation or movement, “what’s the shadow for us?” “What’s the thing that we create unconsciously that’s destructive or harmful, and how are we like the thing we’re trying to change?”

I think the powerful question is, is in any organisation or movement, “what’s the shadow for us?” “What’s the thing that we create unconsciously that’s destructive or harmful, and how are we like the thing we’re trying to change?”