18 May 2016

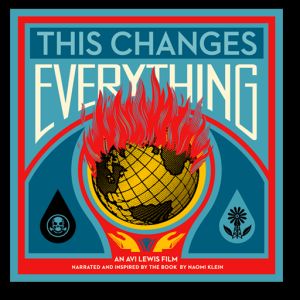

Film review: ‘This Changes Everything’

‘This Changes Everything’, the recent film starring Naomi Klein and made by her partner Avi Lewis, is ambitious in its scope and its reach. We meet those trying to block the expansion of fossil fuel extraction in the US, Canada, India, Greece and other places, as well as those fighting for air quality in China.

‘This Changes Everything’, the recent film starring Naomi Klein and made by her partner Avi Lewis, is ambitious in its scope and its reach. We meet those trying to block the expansion of fossil fuel extraction in the US, Canada, India, Greece and other places, as well as those fighting for air quality in China.The story of the First Nations of Canada coming together to resist tar sands is particularly moving, their conflating the fight against climate change with “bringing our Nation back to life”.

Here is the trailer:

Change on the scale needed to truly avoid catastrophic climate change urgently needs all manner of responses: businesses doing their part, enlightened policy-making, the community-led solutions approach modelled in Transition, and also people standing up for what they believe in, putting their bodies on the line, and speaking truth to power to protect the places they love. There’s no either/or, we need it all, and lots of it. And, as Clive Hamilton recently noted, there are causes for optimism as well as for pessimism.

For Klein, the problem at the heart of climate change is the story we tell ourselves as a culture, the story, as she puts it, of “Nature as a beast we have to break”. It’s a story that reduces nature to a machine that needs to be mastered, analysed, as a set of resources to be plundered and fought over. Yes, that story is a story we urgently need to confront. But there’s another one too that sadly this film doesn’t address.

Why the grey areas are the most interesting

It felt to me like this film set up a very powerful good vs. bad dynamic. To some degree that is justified, and the conflating of climate change and capitalism inevitably draws people into such polarisation. But it is my experience that it is in the mid-ground between these polarities that the really interesting stuff lies in the pursuit of climate action. For example, George Marshall’s great work on how to discuss climate change with those beyond the progressives (“I regard myself to be a radical. However, I now believe that the most radical thing that I can do is to break out of the safety zone of left/liberal environmentalism and actively engage with conservatives”), and Tom Crompton’s work on values and frames, both name-checked in Klein’s book, but which look to have had no impact in the editing suite.

What for me felt missing from this film are the dialogues, the discussions that take place within families, in workplaces, in organisations, in our own heads. What about the climate-concerned people we’ve all met who also don’t think twice about flying to Thailand for a two-week holiday because they “deserve it”? Or the people who work for oil companies but who are very active in their communities, eat organic food and try to save energy at home? Who care about beautiful places, good food, good health? Or the person I met who was an active Transitioner, but whose hobby was skydiving, which required a huge amount of air travel?

When I visited Houston, Texas, a few years ago, I was amazed at the number of people in the Transition group there who worked in the oil industry. It is the points we all find ourselves along the spectrum, these inconsistencies, that are of more interest to me than the polarities.

Oil companies, while still acting as psychopathic, seemingly out-of-control institutions, are not inanimate objects, faceless, soulless machines. They are made up of individuals, some ruthless and selfish yes, but many at varying places on a number of different spectrums, fond of where they live, caring for friends and family. Good people. Confused people. Many of them deeply unhappy and conflicted about the work they do, but unable to summon the courage, or restrained by debt or family pressure from stepping away. Or feeling, as I overheard one man telling another on the train the other day after spending 10 minutes discussing how miserable his job was making him, “but it pays the bills doesn’t it?”

A solutions-free zone?

The strong feeling I had watching this in the cinema was that polarising people as this film does doesn’t help. How about talking to those people, or to their friends or family, with ideas that are infectious and universal? Absolutely we urgently need to be throwing whatever we can into the cogs to try to stop the wheels of the fossil fuel industry from turning. But what we also try to do in Transition is to add to the palette of options activists feel they have at their disposal. Alongside campaigning and standing in front of bulldozers, how about, as at Balcombe, starting a community renewable energy company? Or alongside pushing organisations to divest, working with them to support them to reinvest in the new, local, resilient economy? I did find the lack of solutions in this film, other than some Lakota people learning how to install solar panels, troubling.

Of course, those working within systems such as the fossil fuel industry are also caught up in a dominant system that is geared towards consumption and growth and which has strong defences built into it. But, the film seems to say, “if you are not prepared to lie down in front of a bulldozer for the climate, you’re part of the problem”. That feels to me an unhelpful message, one that will do little beyond raising a cheer among those who have already earned their ‘lying-in-front-of-bulldozers’ stripes. For me, the art of finding common ground is one of the key things we need to develop, and there is little of it here.

On building connection and discrepancy

It is impossible to watch footage of tar sand extraction or mountaintop removal coal mining without a sense that our relationship with fossil fuels has many of the characteristics of the relationship an addict has with drugs. Whatever is in the way of our fix needs to be swept aside, damage to relationships is ignored, our need for a steadily higher dose means we become ever more desperate in order to secure our fix. But breaking cycles of addiction is not done by shaming and isolating, by creating ‘them and us’ dynamics. As Johann Hari writes in ‘Chasing the Scream’, his book about the War on Drugs:

“The opposite of addiction isn’t sobriety. It’s connection … If you are alone you cannot escape addiction. If you are loved, you have a chance. For a hundred years we have been singing war songs about addicts. All along, we should have been singing love songs to them”.

One of the most successful tools for dealing with addiction is Motivational Interviewing, which is all built around trying to skilfully cultivate a sense of discrepancy between the addict’s core values and their daily actions. Had this film been designed for those not already interested/involved with climate change, and to skilfully trigger that discrepancy, that approach could have worked beautifully.

‘This Changes Everything’ is also a film bereft of any humour. Saving the planet is too serious a business, it seems to say, for laughter, for levity. There is only one moment in the film where people laughed, when during a demonstration in India, having attacked the demonstrators, the police themselves turn and run, leading to laughter and cheers in the cinema. Immediately afterwards though, the police are seen shooting some of the demonstrators and we shockingly see them lying dead in the street.

Will this change everything?

Although the title is ‘This Changes Everything’, you are left with the sense that very little is actually changing for the better at all. The contrast between this film and, for example, Al Gore’s recent TED talk ‘The Case for Optimism’ is stark. But it’s not all bleak news. China, for example, pledged in 2014 to peak its carbon emissions by 2030, but a new study suggests they may already have done it. And there are many more such causes for hope, as Gore’s talk sets out.

The kinds of campaigning set out here, the work of 350.org, the divestment movement, are all having great impacts. But alongside that, shoulder-to-shoulder, we also need to inspire and invite people to set to building the new, resilient economies we will need, economies to which many of those currently working within oil companies and others have invaluable skills to contribute. As George Monbiot puts it in a recent interview:

“That’s our crucial responsibility at times like this: to be prepared. To develop the organisations, the narratives, the strategies that can be deployed when the propitious moment arrives. We have missed many such chances in recent years (not least 2008) because we have not been ready”.

It is in the middle ground, away from the polarities of ‘This Changes Everything’ and the almost entirely solutions-focused ‘Demain‘ that, I am left with the impression, the complex web of solutions we need will be found.