16 Mar 2016

Budget 2016: What we are facing isn’t a financial crisis, but a crisis of the imagination.

So George Osborne just delivered his budget. In the same week, the Mauna Loa Observatory released data showing that the rise in CO2 concentrations in 2015 was the largest year-to-year increase during 56 years of research, up to 405.6 ppm, a level not seen in 15 million years. Prof. Michael Mann says “we have no carbon budget left for the 1.5⁰C target, and the opportunity for holding to 2⁰C is rapidly fading unless the world starts cutting emissions hard right now”. Yet, in spite of being a signatory to COP21, such thinking barely figures in Osborne’s Budget, with its foundations in the increasingly shaky argument that a financial crisis necessitates devastating austerity. It includes, for examples, more tax breaks for the oil and gas industry. Yet it strikes me that what we are really seeing, in the Budget and more widely, is a crisis of the imagination. And that’s far more dangerous. Allow me to make my case by showing you two maps.

Map One

The first is taken from the Heart of the South West Local Enterprise Partnership’s ‘Prospectus for Prosperity’ document. Here it is:

Look closely. It is a plan, created by an unelected, self-appointing business elite (the ‘Local Enterprise Partnership’ (LEP)), through whom billions of pounds of government funding will be channelled to promote growth in the south west of England, for how the region should develop over the next 10 years. LEPs were set up by the Conservative government to replace Regional Development Agencies, and are a response to the government’s thinking that increasing productivity is “the challenge of our time”. They argue that we need to set about:

“‘fixing the foundations’ of infrastructure, skills, and science through a devolution revolution delivering long-term public and private investment”.

In this map, the area’s “renewable energy potential”, well that’s all in the sea. It is barely able to contain its delight about the ‘Golden Opportunity’ of Hinkley C nuclear power station which it thinks will create 25,000 jobs, but which actually looks less likely to happen with every day that passes, the Financial Times recently writing that “the case for halting Hinkley is becoming hard to refute”.

The Prospectus allocates ‘Principal’ and ‘Secondary Growth Areas’ based on the wishes of business, not of local people, who haven’t been consulted at all. The LEP Prospectus states that they will deliver 179,000 new houses, but the words “affordable”, “low carbon”, “community land trusts” or “local needs” appear nowhere. Of the 800 new houses recently built, or being built, around Totnes, for example, just one went to someone currently on the housing list. This is social cleansing disguised as ‘economic growth’, ‘job creation’ and ‘removal of red tape’.

“We cannot deliver effective economic interventions without a strong business voice”, they boast. Ah, but whose voice? The LEP map, which embodies in one mad, deluded image all that is wrong about the government’s approach, is all about supporting the agenda of big business in a part of the country where about 80% of economic activity is generated by small to medium-sized enterprises.

Map Two

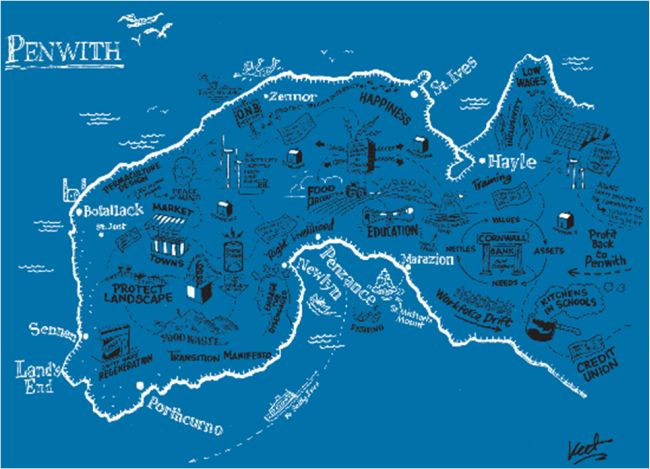

This one was created at a REconomy event last year in Penzance that brought together social enterprises, development organisations, entrepreneurs and others to imagine a new economy for the region.

Sadly it’s not for the same part of the country (would have been nice to be able to compare the two), but you get the idea, and they are neighbours. For the creation of this map, imagination was unleashed. Creativity was invited. Business-as-usual was put to one side. The solutions suggested were those that were rooted in place, in local economies, based on the idea that a stronger economy is one that is better connected, one that maximises beneficial relationships and interconnections. As a result, the solutions in the map are vibrant, possible, inspiring, intriguing and, in some cases, already underway.

Power to the Imagination

If we are truly to shift our economy to one where we have any chance of cutting carbon in the way required, we need to creatively question basic assumptions, the redefine what we mean by ‘progress’. Do we really need to invest in new roads and tunnels when all they do is create more traffic? Is pouring billions into new railways and tunnels with the vast associated carbon emission really sensible, just because that’s what we’ve always done?

How about a vast reforestation programme in order to build flood resilience into landscapes recently trashed by floods? How about investing the billions currently being put into carbon-intensive infrastructure into improving our housing stock, among the worst in Europe? Into stimulating community renewables? New regional banks? Seeing the push for zero carbon housing as a huge opportunity for innovation and new businesses in the same way that we are meant to see nuclear power. Or seeing conserving energy in creative ways (‘negawatts’) as being a greater source for stimulating new business than building new energy generation infrastructure?

THAT is the direction where the creativity, the problem-solving, needed to solve the actual “challenge of our time”, climate change, will come from. Indeed, it’s already happening, as the Penzance event, and many others, and the work of countless groups, businesses and individuals, the success of the film ‘Demain‘, the explosion of new food businesses, urban farms, and so on show. Build on that. Invite ideas. Be bold, dream big.

This Budget introduced a Sugar Tax, which is great. But part of that will be spent to fund “longer school days”. Talk about adding insult to pop-loving schoolkids’ injury. Imagine what else that could have been spent on, and already you’re on the right track.

A budget to stimulate the imagination, now wouldn’t that be a thing?