Monthly archive for May 2015

Showing results 1 - 5 of 6 for the month of May, 2015.

27 May 2015

Julian Dobson is a writer and researcher, as well as one of the co-founders of New Start magazine. His area of special interest is community regeneration and how to create better places. We loved his recent book ‘How to Save Town Centres’ so much that we gave it a glowing review, and thought we’d chat to him too. So we did.

What’s wrong with our high streets today? Why did you feel you needed to write a book about what we can do about them?

I’m interested in what creates good places. If you want to get a feel for how a place is working, visiting the high street, the town centre, gives you a very good idea. It doesn’t tell you everything, but it unlocks a range of issues about how the town, how the place is working. I’ve been interested in this for quite a long time.

Back in 2011 when David Cameron asked Mary Portas to do her review of the high streets I got a bunch of people together to put in a submission to that review. That bunch of people included quite a range of interests, people like Pam Warhurst from Incredible Edible, a guy called Dan Thomson who runs something called Artists and Makers and was previously running something called the Empty Shops Network and was looking at new uses for empty shops. People who are interested in looking at new angles of how to use space within town and city centres.

Back in 2011 when David Cameron asked Mary Portas to do her review of the high streets I got a bunch of people together to put in a submission to that review. That bunch of people included quite a range of interests, people like Pam Warhurst from Incredible Edible, a guy called Dan Thomson who runs something called Artists and Makers and was previously running something called the Empty Shops Network and was looking at new uses for empty shops. People who are interested in looking at new angles of how to use space within town and city centres.

What are the issues we were trying to highlight? Firstly, the conception of the high street purely as a retail space. The colonisation of town centres entirely by shopping has actually stripped away some of the public realm, a lot of the civic society that used to be central to town centres and so what we were talking about really was a rebalancing of the activities that go on in town centres so that you’ve actually got something for everyone, so that you protect the activities and the buildings and the spaces where people can do things other than shopping.

To start to think of what creates space in a much wider context than purely this retail approach which is very much driven not only by the retail industry but by the property industry, and is premised on making quick capital gains from the building and the selling off of retail premises. What we were trying to do was challenge that approach and say that actually there’s a whole lot of other things that have community value that need to be in high streets.

You wrote that “the flatulent promise of retail-led development is a powerful one” and it entices planners and governments, it’s very attractive to them. What’s the best way to challenge that myth that all you need is a glittering shopping centre and everything will be ok?

Part of it is history. It hasn’t always been this way. In terms of looking at how things could be different, first of all you have to remind people that things have been different. They haven’t always been like this. Secondly, you have to start thinking about what that actually creates in the local economy, the idea that the economy is created through retail is nonsense. What retail does is it scoops off people’s disposable income. That’s great, we all need to buy stuff. We all need to go to places where there are nice things to buy, so I’m not knocking shopping, I’m not saying let’s get rid of all the shops. But the shopping is not the economy. The shopping is what happens if the economy is successful.

So how can town centres once again be places which are at the heart of a local economy where people have a sense of ownership of their space, where people have a sense of civic responsibility within their space; so that the goods that are being produced in a place can be sold in that place, so you’ve got that localisation that you talk about a lot with the Totnes Local Economic Blueprints?

And where you’ve got a sense of pride that comes from people actually working to build and to create spaces that are good for people. Shopping is the icing on the cake. But you’ve got to have the cake. You’ve got to have the activity that makes a place function well, and you’ve got to have the activity that makes a place function well for everyone, not just for the people who are well off.

You wrote “real hope involves getting your hands dirty.” What did you mean by that?

I mean that we need to have experimentation and we need to have people who are prepared to get stuck in in whatever way they can do, and whatever way they have the ability and the talents and the context to do. One of the examples I use is Incredible Edible Todmorden. Incredible Edible is literally people getting their hands dirty. Planting fruit and veg in public places, which actually creates a sense of the possibility of the place being different. Not just by saying “here is food to share”, which challenges the idea that the success of the place is all about buying and selling, but actually physically changes the space in the town. It actually changes the look, it changes the feel of the place.

So actually doing things that are visible and physical, like using empty shops, is really useful. Not just because it makes them look nice, but because it shows people that there are different ways of doing things. It shows people that different things can happen. That’s really what I mean by getting your hands dirty. Actually saying “how can we be involved in starting to create and spread these experiments?”

Obviously, people have different skills and abilities, so not everyone can get out and plant free vegetables. Not everyone can do street art. Not everyone can do things in empty shops. But we can all do things that help to make these experiments happen.

A lot of that comes down to self-confidence. To feeling like if you change things, things are going to change. Somewhere like Todmorden seems to have that, and somewhere like Totnes, which appears a lot in the book, and Brixton. Places that don’t have that, did you come across examples where that happened or is it more inevitable to be more top-down in places like that?

It’s more difficult, more challenging … and that’s not surprising. But if you look at where change has happened in the past, one of the places that I went to in researching my book was Rochdale. Now Rochdale was the home of the Co-operative movement, and the Rochdale pioneers, the first Co-operative Society in Rochdale was created by a small bunch of people saving up small amounts of money over a sustained period of time in order to do something that was completely ridiculed when it started.

The creation of the first Co-operative shop was laughed out of court. It’s a question of patience and time. In the more difficult places, it takes longer and it obviously helps if you have governance, central or local, but affirmative and that puts its investment to match the investment of local people.

Where we see things going wrong is where you only have investment by government and official bodies. So you look at the regeneration programmes that took place in lots of places in the 1990s and early 2000s and you’ve got big amounts of money relatively speaking coming in, but the legacy is actually quite limited because once the funding stops, the activity stops. So you need to find ways of using the funding that’s available to enhance local activity and to invest not just in places but in people, and the people who are going to invest their lives in those places and stick around in the long term.

You wrote “ it’s time to raise a glass to the New Economy because it’s the best hope for our high streets.”. What is the New Economy for you, and what does it look like?

It’s very much a blanket phrase that covers a multitude of things. Trying to nail down the New Economy specifically is a problem, we do need to keep it open. But what I think are the characteristics of what I call the New Economy are: first of all rethinking production and consumption.

The illustration I gave in the book was of the growth over the last few years of small breweries. It’s not just because I like beer, but actually if you look at the brewing industry, the way that the big brewers in many places were closed down and small ones, craft breweries owned by local people and creating local character, that’s really important, to see how that reconnection of product and place is happening. So that’s the first thing that I think is important, that it’s much more peer-to-peer. It involves a lot more sharing of knowledge, of space, of collaboration. A lot less emphasis on commercialisation.

The third thing that’s really important is that it has a social purpose often, as well as a commercial purpose. So that sense that the values that are being created and being exploited through business are not just the values of financial gain but the values of creating good places, creating great products and creating a sense of community and society.

You’ll find a lot of people, a lot of entrepreneurs, whether they’re entrepreneurs in traditional business or in social enterprise which is not for profit, who actually have that sense of civic and social value as well as the sense of running a good business. It’s time to actually bring those business values to the fore, to say loud and clear to the people who see our town centres purely in terms of big development, big brand retailers, that actually there are different ways of doing business.

I’m not anti-business. I’m for different kinds of business and different ways of doing business, and business that actually works for the people. Not business that is about extracting value from places and appropriating it into the pockets of the few.

How far would you say are we away from the ideas in your book becoming a much more mainstream way of looking at local economies?

It’s really difficult to tell. I tend to be cautious in that I’ve been around for long enough to see lots of people who say such and such is the next big thing, then it withers. We are actually working in a very hostile climate – I don’t think we should underestimate that.

However, there is a genuine sense in many places that it is time for a change in what we value. That’s the really crucial thing, that’s what underpins all these experiments. What’s happening in Preston (subject of a future blog) is about saying there are different ways of valuing what we do in the city. It’s not just about big development, it’s not just about big new shopping centres, it’s not about the traditional inward investment when you expect some big new employer to solve all your problems. It is about recreating the networks and structures that enable civic life to flourish and I think there is a real appetite for that.

There are still, in many places, the resources to enable that to happen. What we need to see is people stepping up to the plate who are not just within local authorities and the public sector, not just within the voluntary sector, but actually the private individuals who are prepared to say “I’m going to put some of my own wealth, my own assets into this because we want to see places that are good for our children and our grandchildren”.

If you look back to the municipal growth of Victorian cities, you’ll find that there’s a huge amount of reinvestment in places by people who are making money in those places. We’re not really seeing that in the same way at the moment, so we need to be able to say to the individuals who are property owners, who are making money from the places that we live in, to the businesses that are making money from the places that we live in “you’re got responsibility here as well. You should be working with us to reinvest in these places”.

Reinvestment from the private sector is needed to match the new thinking that’s going on in communities and in the public sector and voluntary sector.

A lot of communities up and down the country, rather than being able to focus on the great things they’d like to be able to do, end up rallying around trying to stop awful crap developments from going ahead. I wonder from the research you did for the book what you learnt about the best ways to resist development like that? What suggestions you might give to communities facing something like that?

Often people don’t come together unless there’s a crisis, so I think the first bit of advice is “come together when there’s not a crisis”. Start looking ahead, because the developers, particularly the supermarkets, they are looking ahead all the time, saying “what bits of land can we get hold of, what pub that is currently flourishing and serving the community might we be able to turn into a new store? What are the places that we could be occupying and colonising?”

We need to start the reverse of that process where as concerned citizens we get together, particularly through organisations like Development Trusts, to identify what are the places that we need to keep for our local community and how can we get hold of them. How can we start to make sure that that property, those public places are managed for the benefit of the community? You really need to be as active at a community level to start doing that as the supermarkets are in scouting out land in order to really start to create change.

But we’re a very, very long way away from that. There are a few examples of local organisations that have managed to start owning public assets or landmark buildings and turning them into places that are really useful and valuable for the community again. But we’re a long way from seeing that happen on a significant scale.

How important is it that communities start to own and manage assets?

It’s crucially important. It’s a difficult thing to do because it involves all sorts of skills and often the assets that are most of value to communities are ones that need a lot of investment and a lot of physical investment. But if you look at the pattern of property ownership around the country, you’ll see that increasingly places cannot be improved for local people because of who owns them.

You have the same issue in Totnes with Costa. The people who wanted to sell to Costa were actually based in London. They had no particular interest in Totnes as a place at all. We see that being repeated across the country. Ownership is distant from a place and people who rent out and sell commercial property are doing it without any knowledge and without any concern for the future of those towns and cities.

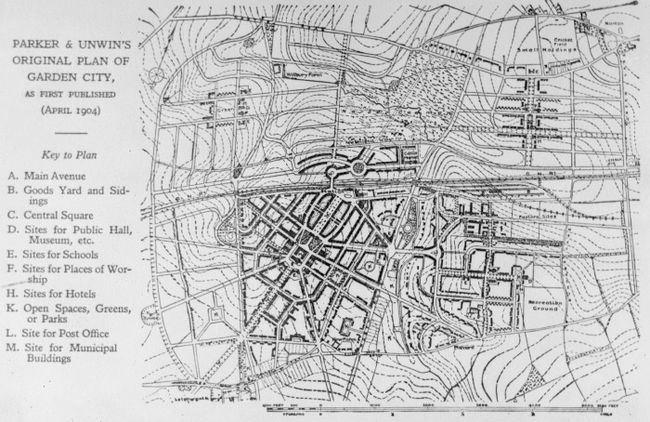

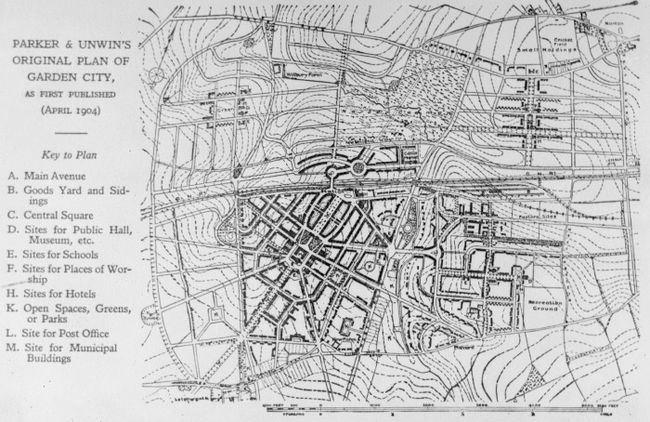

How do we turn that around? You have to do it by starting to put property in the hands of local people. One of the examples I used in the book is Letchworth Garden City which was place that was created to fulfil everything. People talk about garden cities all the time now in this sort of romanticised way, but the really crucial thing about Letchworth was actually property ownership. It wasn’t just that it was a very green space, it was that the property was owned for the benefit of the community. Even now you’ll find that the Letchworth Garden City Heritage Foundation runs the commercial property in the centre of the town in order to reinvest in Letchworth.

How do you retrofit that kind of model to other towns? That’s more difficult but it’s not impossible. Part of that is finding the strategic places that need to be kept for the benefit of the public. So where are the places in our towns where you can start to take action? It might just be one property, but from that you might be able to expand.

There’s an organisation in North Wales called Galeri Caernarfon which has started to buy up a number of properties around the town. After a while you can see how that patchwork might start to change the way the town looks and feels and start to change the economic flows within the space. But it will take time.

Some of the best examples, places like Coin Street on the South Bank of the River Thames in London, places like Westway Development Trust in West London … they’ve taken 30-40 years to reach a point where they’re now successful and where they’re property owners to be reckoned with in their own right. So it is going to take time but it is important because otherwise whatever community organisations do within their towns is going to be vulnerable by somebody else coming in, buying up those assets, and then using them for purposes that are not beneficial to local people.

You mentioned Totnes, which appears quite regularly in the book and Brixton as well. I wondered what it was that you saw in the places that were doing Transition that was particularly of interest to you?

What the Transition movement does incredibly well is to bring together the long term challenge of climate change as an over-arching impetus for action with small action at a local level. Small-scale experiments which are practical, which resonate with local people, which look as if they’re doable, and that can engage people at a practical and meaningful level.

A lot of the talk about climate change is quite disempowering in that it is all so big and so complicated and it looks so difficult to do anything about it. What the Transition movement actually does really well is connect up the big issues and the local issues and show you that change can happen at a local level.

There is something in the middle that still needs to be explored, which is how to bring that Transition thinking into the spaces within cities and governments where decisions are being taken. That will start to turn the tide and so far there is still quite a lot of work to be done to impact on those institutions and to change the way that institutions behave.

But what Transition does really well is show that local people can make a difference at a local level, and that you can start to do it in ways where you can see economic flows can start to change. You can start to reconnect producers and consumers. You can start to say “we can eat our food in different ways, we can choose our shopping in different ways, we can rearrange our economy in order to reinvest in the locality”

What the Transition movement is doing really well is acting as a forerunner in order to show what the possibilities are. We now need others to start taking up that thinking and that action at a wider scale.

Read more»

26 May 2015

Today’s guest blog on the theme of community engagement is by Tina Clarke, a community organiser and consultant in the US. She is also a Certified Transition Trainer who is part of the international training team and a community resilience consultant, as well as being one of the trainers behind Transition Launch Online. She is also involved with Transition Northfield:

“As a professional community organizer and consultant, I was intrigued, in 2008, to see the list of Transition Principles. As I began to work with the Transition model, I was impressed by the principles that had been chosen. Over the past 35 years in social change movements, I have seen few such “neutral” and useful guidelines for engaging the community.

Here are some reasons that I encourage Transition Initiatives to use the Transition Principles when planning events, activities, projects and other kinds of outreach.

Transition Town Totnes inspired a global movement of local action based on fun instead of fear! The eight Transition Principles help you create fun, welcoming activities that bring people together to connect, support each other, and get practical work done. The Transition Principles help you choose projects and organize events that are more likely to engage a broader number of people.

The Transition Principles combine many key elements of successful community involvement. For example, all communities, organizations, cultures and social movements depend upon principles – a set of values and good intentions – that help the community decide what to do and how to work together. Good ideas and fun events can bring people together, but shared, valued principles keep people coming back. Events that promote a particular business, or seem focused on attracting “customers” or “members” may eventually start to lose people if it seems that the business or organization’s goals of “getting” something from people is more important than contributing to the greater good. (Image, right, shows Transition Northfield’s first birthday party, in 2011).

The Transition Principles combine many key elements of successful community involvement. For example, all communities, organizations, cultures and social movements depend upon principles – a set of values and good intentions – that help the community decide what to do and how to work together. Good ideas and fun events can bring people together, but shared, valued principles keep people coming back. Events that promote a particular business, or seem focused on attracting “customers” or “members” may eventually start to lose people if it seems that the business or organization’s goals of “getting” something from people is more important than contributing to the greater good. (Image, right, shows Transition Northfield’s first birthday party, in 2011).

A good set of principles help you communicate the meaning and purpose of the work. Ultimately, generosity attracts more interest than self-interest. Respect, collaboration and meaningful values are more likely to be successful in building community.

Here’s a few tips on how to use the Principles of Transition as a tidy, handy guide as you plan projects and outreach:

1. Positive Visioning

“Our primary focus is not campaigning against things, but rather on positive, empowering possibilities and opportunities.”

By organizing activities and events that inspire and deepen a positive vision of the future, you not only attract more people. You also avoid getting stuck in negative attitudes that turn people away. Transition’s focus on positive action helps you connect with a much broader range of neighbors than would respond to a “sustainability” or “environmental” event alone, or a “family” event, or an “Inner Transition” event alone.

2. Help People Access Good Information and Trust Them to Make Good Decisions

“Transition Initiatives … recognise the responsibility to present this information in ways which are playful, articulate, accessible and engaging, and which enable people to feel enthused and empowered rather than powerless…The messages are non-directive, respecting each person’s ability to make a response that is appropriate to their situation.”

Everyone needs to feel respected. We each need to be seen as able to come to good, wise conclusions. Sharing information by saying, “I find this interesting” or “I am wondering if you might want to know about some information I received” shows deep respect for other peoples’ intelligence and their freedom to come to their own conclusions. Respect and welcoming of diverse points of view is essential to engaging your community.

3. Inclusion and Openness

“Successful Transition Initiatives need an unprecedented coming together of the broad diversity of society. They dedicate themselves to ensuring that their decision making processes and their working groups embody principles of openness and inclusion…[There is] no room for ‘them and us’ thinking.”

“Bring your passion and make that…contribution – if there isn’t a project working in the area you are passionate about, create one!!”

Embracing diversity – listening and learning from everyone in your community – is a foundation of broad engagement and community-building across differences. Make yourselves learners. Go to others rather than expecting them to come to your events. Ask questions, participate in other communities, and ask for advice about how to organize events that will feel welcoming to diverse sectors of the community.

4. Enable Sharing and Networking

Instead of telling people what to do, or trying to recruit them to do a plan you or others have decided, Transition emphasizes sharing information, networking, and seeing what emerges from friendly connections between people who live near each other.

Sometimes it’s hard to get existing local groups and leaders to accept how important sharing and networking is to community-building. Organize fairs, Open Space Technology conversations, forums, potlucks and other group “mingling” and small group conversations to help everyone realize that “no one is telling anyone what to do” – we’re all curious to see what practical projects emerge.

5. Build Resilience

“Transition initiatives commit to building resilience across a wide range of areas (food, economics, energy etc) and also on a range of scales (from the local to the [global])…”

Our goal is to build local resilience. We’re not taking on a large area, nor trying to get hundreds of thousands of people to do what we think they should. Instead, we focus on connecting with our neighbors.

Many of your neighbors will be interested in resilience because it is a broad goal that includes many kinds of projects and activities within it. Your proximity brings you together for mutual benefit.

The key to engagement is stressing the open-ended exploration that is Transition. When you talk to people, note that “Transition is a verb”: we do it; we decide what and how to do it.

‘Most communities in the past had – a generation or two ago – the basic skills needed for life such as growing and preserving food, making clothes, and building with local materials.”

To engage lots of different kinds of people, organize lots of different kinds of practical, hands-on events and projects. Stretch yourself into new arenas!

6. Inner and Outer Transition

“Transition thrives because it enables and supports people to do what they are passionate about, what they feel called to do.”

I encourage you to read about this principle, at the Principles link, and on the TN.org website. Inner Transition reminds us that the foundation of resilience is our relationships with the people in our community. Perhaps some people don’t like each other. Perhaps people don’t know what to say in order to connect. In addition, expect that local political issues will inevitably arise and cause people to feel alienated from each other. Learning how to stay connected and communicate with respect is a great skill that lots of people still need support and tolerance to learn. With a bit of humor, and some practical and social benefits when we spend time together, people often find some interests in common.

I encourage you to read about this principle, at the Principles link, and on the TN.org website. Inner Transition reminds us that the foundation of resilience is our relationships with the people in our community. Perhaps some people don’t like each other. Perhaps people don’t know what to say in order to connect. In addition, expect that local political issues will inevitably arise and cause people to feel alienated from each other. Learning how to stay connected and communicate with respect is a great skill that lots of people still need support and tolerance to learn. With a bit of humor, and some practical and social benefits when we spend time together, people often find some interests in common.

Then, connected on our positive, practical projects, we can focus on helping each other be ready and be proactive influencing our future rather than letting it happen to us.

These ideas make sense to everyone. As you change your focus from climate crisis to a focus on building collaboration with your neighbors, people will be curious. Do your inner work so you’re ready to greet them with a smile and warm interest in who they are and what inspires them!

7. Transition makes sense – the solution is the same size as the problem

Most of us experience powerlessness at times – feel overwhelmed by the scale of the challenge. Transition encourages us to work on the problem in friendly, task-oriented, small groups. These social connections, and feelings of accomplishment, help keep us going. The smaller tasks make it easier to make visible progress. By keeping the work more local and practically useful, we engage more of our neighbors.

Most of us experience powerlessness at times – feel overwhelmed by the scale of the challenge. Transition encourages us to work on the problem in friendly, task-oriented, small groups. These social connections, and feelings of accomplishment, help keep us going. The smaller tasks make it easier to make visible progress. By keeping the work more local and practically useful, we engage more of our neighbors.

8. Subsidiarity: self-organisation and decision making at the appropriate level

“[T]he intention of the Transition model is not to centralise or control decision making, but rather to work with everyone so that it is practiced at the most appropriate, practical and empowering level…”

There’s an old bit of wisdom from research and praxis on community involvement: if you want people to participate, they need to have the power to decide, create and do, in their own way. No matter how wonderful your top-down idea is, it will fail to gather the support it could if it was a conversation, a “bottom-up” process, where together we engage, and support, each other.

© Tina Clarke, 2015, TinaclarkeOZ@gmail.com, www.BeyondDependency.org

Read more»

22 May 2015

The internet and social media have so changed our world and our brains in a relatively brief period of time. Expressions like “I’ll check in my spam folder” would have led to puzzled, indeed slightly revolted looks even 10 years ago, but nowadays we’re all at it. While I avoid Facebook like the plague, I do like Twitter, but have recently noticed a rather strange phenomenon. I seem to be of great interest to rather a lot of attractive young women.

Take “Lily” for example. She follows me, very good of her, but seems to spend most of her time on the beach in a bikini, and tweeting deep stuff like “kinda wanna go on a date, kinda want to get hit by a truck too”, and tweeting celebrity-related links and stuff like “15 Pictures That Will Make Your Heart Stop” (sounds like a bad idea – I didn’t follow the link).

Then there’s “Andrea”, who shares wisdoms like “for a smart woman a man is not a problem, for a smart woman a man is a solution”, and retweets such a wide and eclectic range of stuff that she’s hard to figure out, frankly. Oh, and she wears a bikini too.

“Fabia” seems more set on tweeting stuff about fashion and BMW adverts, and, erm, one of my tweets which mentioned a new book, ‘People Powered Money’, about local currencies. I’m not saying it’s impossible that someone seemingly obsessed with tan lines, BMW convertibles and fashion is also intrigued by how to implement a new currency in her community, but it did make me a tad suspicious.

There’s “Bethany” who, what are the odds, describes herself as “Sex, Wine and Rok’n’Roll”, oddly exactly the same as “Andrea” does, who also wears a bikini, and as well as tweeting about One Direction, American Football players and wisdoms like “I wish… but don’t know whome”, also feels inspired to share with her followers the link to my review of Julian Dobson’s book ‘How to Save Town Centres’.

On closer inspection, there are loads of them. “Dixie” tweets stuff like “a woman’s mind is cleaner than a man’s – she changes it more often”, and so it goes on. And on. Now, much as I might like to think that Transition has once again broadened its appeal into a whole new demographic whose allure previously eluded it, I have my doubts. As a rather naive social media person, I did some asking around, and I think I have got the measure of “Bethany”, “Lily” and the rest of them.

The more followers a Twitter account has, the more money it’s worth. Apparently, Lady Gaga could sell her Twitter account for $9,467,229, were she minded to do so. Twitter itself is apparently worth $10bn, which means that if the UK Government decided not to renew Trident missiles, it could spend the money it saves buying Twitter. I have no idea what purpose doing such a thing would serve, but it could.

I went to an app called TweetValue which claims to be able to value your Twitter account. Mine is apparently worth $3155 (about £2038)! So, call me suspicious, but I don’t think “Bethany” and her friends actually exist. I think what happens is that people create Twitter accounts with the aim of trying to get the highest number of followers, so they can sell them. And presumably, our bikini-clad friends and their inane postings are imagined to be a good way to attract lots of followers. Rather than the links to books about local currencies and the regeneration of local high street economies which, sadly, are probably less of a lure.

Heaven only knows where anyone would actually sell a Twitter account. Presumably if anyone following me found that all of a sudden all I tweeted was adverts for shampoo or dog food, they’d quite rightly stop following me, making the whole thing rather self-defeating.

It’s all rather bizzare, and an indication of how far we’re moving away from an economy that is actually based on people actually doing real things with real stuff. We increasingly have an economy, as comedian David Mitchell put it, “based on selling lattes and ringtones”. But flimsy and unsubstantial and soul destroying though that is, it’s still a few steps above an economy based on poorly paid students on zero hours contracts sitting at laptops pretending to be vacuous imaginary attractive women in bikinis in order to create value for Twitter accounts. When your economy reaches the stage where that is presented as “work”, something is deeply, deeply wrong. There’s a new economy to be built, that’s already being built, and it’s one that will nourish and sustain in a way that what we might now call the “Bethany Economy” never could and never will.

The whole thing is somewhat troubling. But it has given me a good clue as to how I might boost my followers on Twitter. I’m ordering my bikini first thing tomorrow. Brace yourselves.

Read more»

12 May 2015

It’s not often that I’m won in a competition. Transition Wilmslow entered some competition thing that REconomy ran a while back in which a talk by me was the prize, they were first out of the hat, so several months later I boarded the train to Wilmslow, 11 miles south of Manchester, in the north-west of England.

It’s a wealthy town, the seat of George Osborne, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and is apparently one of the most sought-after places to live after central London (thanks Wikipedia). Sir Alex Ferguson lives there. It’s the only town I’ve been to which has, on its high street, an Aston Martin showroom with a car on its forecourt for sale at £118,000. I didn’t buy it. Like most such places though, that’s only half the story. The gulf between rich and poor in the town was the subject of Doves’ track ‘Black and White Town’ (the band went to the local school).

Transition Wilmslow was started by Rachel Corrigan, in 2010. Shortly afterwards, Pippa Jones was driving home and stopped at a progressive service station on the M6 (there is one apparently) and found a copy of The Transition Handbook and decided when she got home that she wanted to do Transition in Wilmslow. She saw an advert in a shop window asking for others who were interested, and the group started to grow…

Now, in 2015, Transition Wilmslow are very active, but like many Transition groups I meet, feel they aren’t doing much. In order to counter that belief, here is some of what they’ve done so far:

- Food Group: wanted to set up a Community Garden, originally they had the idea that they needed a field, but when one didn’t turn up, they contacted the council who suggested they use the end of a park called The Temp. Now features fruit trees and raised vegetable beds. Have also planted two other orchards, and run a ‘Seedy Saturday‘ event.

- Open Space events: on various subjects

- Transport Group: has worked with Cycle Wilmslow to promote family cycling, and to support the local 20’s Plenty campaign

- Green Drinks: every month

- Film Nights: a very popular regular series of film screenings

- ‘Love Wilmslow – Love Our Planet’: an event with Churches Together in Wilmslow

- Energy Group: won some funding through LEAF a couple of years ago which funded a thermal imaging camera which has been used to assess 100 houses. A number of energy surveys have been done too, with energy monitors available for people to use for free

After meeting the group we went to visit The Temp garden, apple trees laid out on a triangular grid so that raised beds would fit between them. Only one ‘triangle’ of raised beds has so far been planted but it featured all manner of veg growing well.

Then we walked to Lindow Moss, a huge raised mire peat bog on the edge of Wilmslow. Lindow Moss is perhaps best known as the place where ‘Lindow Man’ (or more correctly ‘Lindow II’) was found in 1984. This was a ‘bog body’, preserved by the sphagnum moss, since his ritual murder and burial around 2,000 years ago. More recently, soldiers returning from the Crimean War with syphilis found themselves, understandably, not welcome at home any longer, and were kind of exiled to the Moss, where they made a rather miserable living cutting peat.

Lindow Moss has been used for peat extraction for centuries, and the way extraction rights were given had shaped the landscape. As we entered the Moss, we passed beautiful long thin fields, bordered by very old willows, known as ‘Moss Rooms’, now turned back into grazing. Some parts of the Moss haven’t been used for peat extraction for many years, and have begun natural regeneration to woodland. It’s a beautiful, tranquil place with lots of birdlife.

The heart of the site is another matter altogether. The peat was laid down over many thousands of years, and 4,000 years ago was a pine forest which was then taken over by sphagnum moss. Deep in the peat many 4,000 year old pines still exist, or at least did until the peat extraction company which owns the site began cutting the peat, and, in effect, chipping the trees where they stood. Standing looking out at, as far as the eye can see, industrially harvested peat, is heart breaking. Here and there there’s what remains of a stump of an ancient tree.

Peat bogs can hold 20 times more carbon than a forest, and are vital to the fight against climate change. Yet here they are being torn up to provide low quality lining for hanging baskets and for compost. The Guardian’s ‘Keep it in the Ground’ campaign feels just as relevant to Lindow Moss as it does to the Athabasca Tar Sands. The company that own it have applied for planning to build 14 executive homes on the edge of the Moss to supposedly raise the money to resinstate the Moss as peat bog, a proposal that has divided opinion in Wilmslow, somewhat akin to a “vote for me or the kitten gets it” kind of approach.

John Handley, Professor Emeritus of Landscape and Environmental Planning at the University of Manchester, joined the group around this time, bringing huge expertise, and founding the Planning and Environment Group. The group has been feeding into various Local Plans, their input has led to significant changes in those plans. They also undertook a Landscape Character Assessment, surveying the local area, the Lindow Moss in particular, getting lots of people out, learning how assess landscapes and, as John put it to me, “having a lot of fun”. Exploring the area led to a far richer understanding of it, including, as he put it, “we found ourselves in ‘informal landscapes’ (that’s overgrown, wild places to you and I) where clearly teenagers do a lot of growing up”. You get the idea.

Given the recent application from the site’s owners for housing and reinstatement, John and the group brought together lots of local groups with an interest in the place which led to a commitment to produce a ‘New Vision for Lindow Moss’, to “restore, conserve and celebrate this unique landscape”. They have been exploring how it might be reinstated as a carbon sink, how it might be protected and improved for recreation and exercise, how its history might be presented and interpreted (at present there is nothing that marks the site where Lindow Man was discovered. It could also be a great site for green tourism.

Since then, the group have held a Dawn Walk for Lindow Man, on the 30th anniversary of his discovery, and run a series of events, meetings and exhibitions. At one point on the walk we stopped to see the trunk of a 4,000 year old pine tree, a very useful thing to see if you want to get some kind of a sense of perspective on time (see photo above). After a long and fascinating walk across the Moss, we ended up back in town, at the Friends Meeting House, for the evening’s event. After a great potluck supper, I gave my presentation.

It’s not every day you get to give a talk on Election Night, so that was a theme I returned to regularly during the talk. Here is a podcast of it:

Afterwards we had a great Q&A session…

… and then retired to the pub round the corner. Next morning I met with the group and then ran me through their work and we talked about ideas for how they might move their work forward. We talked about REconomy, Caring Town Totnes, Inner Transition, bringing some business thinking to the amazing work they have already done, and whether a community buy-out of the Moss might be an option, as a carbon sink.

It was a fascinating trip, with a great group doing great stuff. Like every group I visit, they tell me they don’t think they’ve done much, so I ask them to tell me what they’ve done, and 20 minutes later everyone is feeling rather proud of themselves. I said to them what I say to every group I meet who ask the same questions – when did you last pause to celebrate what you’ve done? When did you last stop, take a breath, pat each other on the back and celebrate? There is then a moment where everyone looks at each other and realises that, actually, they hardly ever do. This is a marathon, not a sprint, and celebration is a key element of us sustaining ourselves. Wherever you might be reading this, please pause for 10 seconds to give Transition Wilmslow a short but enthusiastic round of applause. Then give yourself one too.

My thanks for Transition Wilmslow for winning me (!), for their wonderful hospitality, especially Pippa and Anthony, my hosts.

Read more»

6 May 2015

For the next two months here we will be talking REconomy, looking in depth at this aspect of Transition which is about creating new enterprises, new economies, new livelihoods. We’ll talk to entrepreneurs, to people in local authorities embracing this approach, to people about to launch local currencies, to people around the world working to make this happen. Something remarkable and vital is happening, and we want you to be blown away by it.

When I visit Transition groups around the world, I hear many of the same questions over and over. “How do we engage a wider cross-section of our community?”/”how do we make a living out of this stuff?”/”how do we build stronger bridges to the local council and local businesses?”

REconomy is one of the best responses to all these questions, offering a series of activities, and a fresh way of thinking that meets more widely perceived needs, while also building a real relevance to far more people than just talking abstractly about “building local resilience”. It’s the invitation to shift our thinking, shift what we do, and step up in truly exhilarating ways.

Central to it is the idea that WE can do this, that creating the new economy that better meets our needs starts with us, here, now. In terms of what REconomy is, I will assume by this stage you are familiar with the general idea, and if not here is Fiona Ward to give you an introduction:

For me, there are several key leap forwards at the heart of REconomy, steps away from what is expected of those working to make the world a better place, which have huge promise in terms of scaling the ideas at its heart up to another level. Let’s go through them one by one:

1. From “anywhere” to “here”: one key aspect of REconomy is that it is about economics that are rooted in place. Most business responses, such as those being touted by candidates in the runup to the Election, have no sense of place. ASDA’s solution to providing food to people, for example, looks exactly the same wherever in the country you find it. But REconomy enterprises emerge from, and embody the places from which they emerge. For example, Brixton Energy could only have come from Brixton and is embedded in it.

The same applies for many of the examples below, mostly drawn from the UK: it’s about creating a new economy that’s rooted in the place, the culture, the history, the hopes and dreams of a particular place. One example of this is in the role that local currencies play in celebrating local history and culture. For example, the Exeter Pound, set to launch September 1st, will feature on its £5 note Adam Stansfield (see below), former Exeter City number 9 who died young from cancer, and whose Number 9 shirt was then retired. Much of the football club’s fundraising work has since been around cancer prevention, in his memory. The story of the Exeter Pound, and how they are, from the start, rooting it in the local community, is told in our Exeter Pound podcast.

2. From theirs to ours: who owns the key assets in a community plays a big role in who is able to meaningfully affect change there. Transition is very ambitious, wanting to change the way the places we live feed themselves, house themselves, employ themselves, power themselves. Being able to do that requires access to more capital, popular support and ability to move fast and to make things happen than we are used to. While owning assets brings risks, it also brings opportunities.

This is particularly important in the context of austerity and local authorities keen to jettison responsibility for land, buildings and other assets, there is an opportunity for community groups, whether actual Transition groups, or Transition-informed community groups, to begin to pull together a portfolio of assets which can then be used as the foundation for doing other projects. The community ownership of assets is a key strand of the REconomy approach.

3. From “divest” to “reinvest”: the divestment movement is gathering pace around the world as the message sinks in that if you hold investments in fossil fuels, you want to be among the first out of them, not among the last still holding onto them. Many individuals and organisations now find themselves rethinking where and how to invest. Community renewables have created the most ambitious investment opportunities for people so far.

For example, Bath & West Community Energy have thus far, including groups they have partnered with, raised nearly £10 million through 7 community share offers, ranging from £350,000 to nearly £3 million. West Solent Solar, which grew out of New Forest Transition, raised £2.5 million for a community solar farm. In Belgium, Vin de Liege, which emerged from Liege en Transition, raised €2million to create a community vineyard.

But investment opportunities need not be so huge. The Green Valley Grocer in Slaithwaite raised £18,000 from local people to reopen a grocers shop as a Co-op. As we’ll see below, the Local Entrepreneurs’ Forum model is about the investment into new enterprises of a lot more than just money, but community engagement and support. In the many and growing discussions about divestment, little is said about what else those funds might support. For Transition groups who are seeing and supporting a number of new enterprises emerging around them, pulling those together to form a kind of ‘portfolio’ of local investment opportunities might be a way to invite divestment to turn into investment.

4. From “someone should” to “let’s”: the current election campaign in the UK (nearly over) has seen lots of grand promises, especially around jobs and housing. “We’ll build 200,000 houses”, “we’ll build 300,000” … “we’re the best, because we’ll build 500,000!” Yet if what’s already being built is anything to go by, there are houses and there are houses. There are what the market offers, “affordable houses” that nobody can afford, which increase debt and carbon emission, and which are based on a model that extracts wealth to distant investors, and then there are those such as Lilac Leeds and Transition Homes, that are approaching the creation of new housing in a way built around affordability, sustainability and the maximum benefit to local economies.

The new Enterprise Centre being built at University of East Anglia is taking the concept of local materials to a mainstream audience in a fascinating way. The walls are being built using thatched panels, so it is the walls, as well as the roof, that are built using local thatch and local skills (see right). Imagine the impact on local economies of starting with what’s local being where most developments begin, like starting planning for each meal starting with “what’s growing in the garden?” rather than “what’s in the freezer?” It’s an approach that Totnes Community Development Society’s Atmos Totnes project will be using on an 8 acre site as a key strategy for community economic regeneration.

The new Enterprise Centre being built at University of East Anglia is taking the concept of local materials to a mainstream audience in a fascinating way. The walls are being built using thatched panels, so it is the walls, as well as the roof, that are built using local thatch and local skills (see right). Imagine the impact on local economies of starting with what’s local being where most developments begin, like starting planning for each meal starting with “what’s growing in the garden?” rather than “what’s in the freezer?” It’s an approach that Totnes Community Development Society’s Atmos Totnes project will be using on an 8 acre site as a key strategy for community economic regeneration.

Similarly, there are jobs and there are jobs. Over the past few years in the UK, a million public sector jobs have been replaced by minimum wage jobs, and more than one fifth of UK workers earn less than the living wage, living hand to mouth, often requiring government benefit support to make up the gap, a subsidy to the private sector. Most REconomy enterprises are committed to paying a Living Wage, and to enshrining workers’ rights from the outset.

Rather than assuming either that voting will create the kind of world we want, or opting out of voting, I’m with Dougald Hine on this one, it’s not about ‘Don’t Vote’, rather ‘Don’t Just Vote’. Rather than complaining about the energy companies, the supermarkets, the housing developers, REconomy is about becoming our own community energy companies, food systems and housing projects. It’s an attitude summed up beautifully in a newspaper article last week about the new Transition Neath in Wales, which quoted them as saying “it’s a negativity free zone — we will be focused on what can be done rather than what can’t”.

5. From “Old Boys Network” to “Everyone an Investor”: the conventional approach to funding new economic activity is to seek either investment from the bank/investors, or government funding. The Local Enterprise Partnerships represent the Old Boys’ Network approach, a model for distributing government Regional Growth funding based on who you know. As a result they tend to be about new bypasses, new regional distribution hubs, and the preservation of business as usual. But business as usual is no longer an option. As Naomi Klein puts it in This Changes Everything, “there are no non-radical solutions left”.

So how can we, as communities, fund the new entrepreneurs, the new enterprises and innovations that we need, ourselves? One of the best models for this is the Local Entrepreneurs’ Forum, begun in Totnes (the next one is May 14th, very soon) and now popping up elsewhere (the first outside Totnes is in Brixton on June 2nd, with others to follow).

Another way of doing this, and often a good follow up to a LEF, is crowdfunding. Many Transition projects have successfully used crowdfunding. Here for example is a great crowdfunding appeal that just kicked off in Totnes, looking at putting in place the infrastructure to enable the local food economy to grow, process, store and sell those most staple of food, grains. It’s the Grown in Totnes project. Please support their appeal:

6. From niche to mainstream: these ideas are rapidly moving out of the niche and into the mainstream. One of the most exciting examples of this has been the work the Centre for Local Economic Strategies have been doing with Preston Council, looking at how the main stakeholders in the city spend their money, a kind of Economic Blueprint for the city. Together, the stakeholders (two local authorities, a higher education institution, two further education institutions, police, fire and rescue, hospitals, and housing associations) spend £750 million a year, of which only 4% is actually spent in Preston itself, and only 29% in the county of Lancashire. The report identifies a number of strategies by which a shift in focus could “enable a good local economy”. It’s work explained in this short video from New Economics Foundation:

A similar process is underway in Bristol as the City Council explore how weaving the Bristol Pound into its procurement approach can boost keeping money within the city. This idea, that we base our economic planning on the Multiplier Effect, is growing fast. REconomy is ahead of the curve.

7. From “not again!” to “never again”: all too often the conventional approach to economics and development is something that is done to communities, rather than by them. All too often, another proposal for a supermarket, for a new, bland, identikit housing development, are met with raised eyebrows and a resigned “not again!” Communities find themselves unable to resist developments due to the ability of developers to hire better lawyers on appeal and to steamroller local opinion out of the way.

However, if communities are able to own assets, to generate revenue through their use, then their ability to influence outcomes locally is transformed. It puts the community in the position to be able to say “never again” with a firm sense of purpose, to make sure rubbish housing developments don’t happen by buying the options on the sites and either not doing them at all, or doing them, but so, so much better. Our “never again” becomes assertive, empowering, yet underpinned by a commitment to doing things much better, rooted in the genuine wishes and desires of our local economies, an approach we have previously defined as a ‘SWIMBY’ approach (“Something Wonderful In My Back Yard”) as opposed to a NIMBY approach.

8. From ‘Clone Towns’ to ‘Places of Possibility’: Growing Communities in Hackney are a brilliant local food project in the heart of London. They describe themselves as “a community-led organisation based in Hackney, North London, which is providing a real alternative to the current damaging food system”. One of the most fascinating aspects of their work, for me, is the following diagram which, based on their experience, is their attempt at speculating on what a more localised food system would look like for London, their answer to the question “could London feed itself?”

It’s quite complicated, and its colour scheme is really best viewed through the kind of glasses you are advised to use to watch an eclipse through, but the key point is that looked at through REconomy glasses, it’s extraordinary. It’s really the model for a new food economy for the city.

It’s an invitation to innovation and entrepreneurship and creativity the likes of which we haven’t seen for generations. And the coolest thing is that it is already happening. Across the city there is a flourishing of new enterprises: new urban market gardens, people growing mushrooms in abandoned Underground stations, craft breweries across the city, new orchards being planted, new markets, such as Crystal Palace Transition Town’s amazing Food Market which last week was a runner up in the BBC Food and Farming Awards, making it the joint second best market in the country. Where are the best places to look for the creativity, the innovation, the flavour, the taste, the community. the laughter, the future? At Lidl or Asda, or in this emergent new model? As Julian Dobson put it in his brilliant ‘How to Save Town Centres’:

“The best future for our town centres is not merely as places to buy, but as places to be; places where we can live and act as citizens rather than as consumers. Then they can be places where we rediscover local identity and community, where we can be more fully alive and more fully ourselves. As many a shopkeeper has said, why settle for less?”.

Why settle for less indeed. We stand on the cusp of a historical shift, a historical transition, as economic globalisation starts to go into reverse. Savour the moment – it is rich with possibility. Enjoy our exploration of REconomy, and do let us know your thoughts.

Read more»

Back in 2011 when David Cameron asked Mary Portas to do her review of the high streets I got a bunch of people together to put in a submission to that review. That bunch of people included quite a range of interests, people like Pam Warhurst from Incredible Edible, a guy called Dan Thomson who runs something called Artists and Makers and was previously running something called the Empty Shops Network and was looking at new uses for empty shops. People who are interested in looking at new angles of how to use space within town and city centres.

Back in 2011 when David Cameron asked Mary Portas to do her review of the high streets I got a bunch of people together to put in a submission to that review. That bunch of people included quite a range of interests, people like Pam Warhurst from Incredible Edible, a guy called Dan Thomson who runs something called Artists and Makers and was previously running something called the Empty Shops Network and was looking at new uses for empty shops. People who are interested in looking at new angles of how to use space within town and city centres.

The new Enterprise Centre being built at University of East Anglia

The new Enterprise Centre being built at University of East Anglia