14 Jan 2013

The British bean is back: an interview with Josiah Meldrum of Hodmedod, and a Transition Culture competition

Transition initiatives have spawned a number of fascinating new enterprises, and in today’s post we’ll be looking at one of them you may not have come across yet, Hodmedod’s Great British Beans, which has emerged from work of Transition City Norwich and East Anglia Food Link. What follows is an interview with one of its founders, Josiah Meldrum. The beans project was first mentioned in an interview I did with Josiah for a Transition Podcast a year ago, and is now at the commercial stage. Below you will find the audio of our interview which you can either play or download to listen to while you are planting out your garlic, the transcript, and, at the end, a competition to win some, and a code to buy some at a discount. What a treat. You’re going to enjoy this. I love the bit when Josiah says:

“we discovered was that there was an assumption that no-one would want to eat the beans, but no-one had bothered asking anyone whether they wanted to eat the beans”.

Before Christmas I got my hands on my first box of Hodmedod’s Great British Beans and fantastic they are too. I wondered if you could just tell me a little bit about where they’ve come from – what’s going on, what are you up to?

I suppose the simple answer is they come from somewhere in the fertile crescent 10,000 years ago, the dawn of agriculture. They’re the first and only bean we had in Europe until the Middle Ages when we discovered a whole new group of beans on the other side of the world in the Americas. But as far as we’re concerned, it all started 2 or 3 years ago with some work that East Anglia Food Link began doing with Transition City Norwich looking at what would make a more resilient diet, a diet more suited to our climate and reducing our dependency on imported protein crops and reducing the meat content.

One of the things that became really clear was that we needed to eat more beans and peas, not only because they’re a good substitute for meat, but also because they’re important in agricultural rotations – they fix nitrogen, they’re a good break crop from cereal growing. We thought that we were going to have a really big task on our hands encouraging farmers to grow more beans and peas.

We went out and began talking to farmers in and around Norwich and Norfolk and we discovered that they are in fact growing loads of beans and peas, and that which wasn’t being fed to animals was being exported, mainly to North Africa, the Middle East, and some of it also into India. There simply wasn’t any demand or market for British Grown beans in Britain.

I think that’s mainly because the type of beans being grown were fava beans – broad beans as we’d be more familiar with them – and broad beans are traditionally seen as a fresh product rather than a dried product . Eating them fresh only really began in the Middle Ages when we stopped eating them dried.

So these are, to all intents and purposes, dried broad beans?

They’re a small variety of dried broad bean, that’s all they are.

Would people have encountered them – apart from broad beans that we’re familiar with – in any other way? Is there any other way that people listening to this might have encountered such beans in their daily culinary adventures?

It’s extremely unlikely. I think sometimes they’re used as a bulking agent in ready meals, as cheap protein in the same way that soya is, but I don’t think very much of that happens.

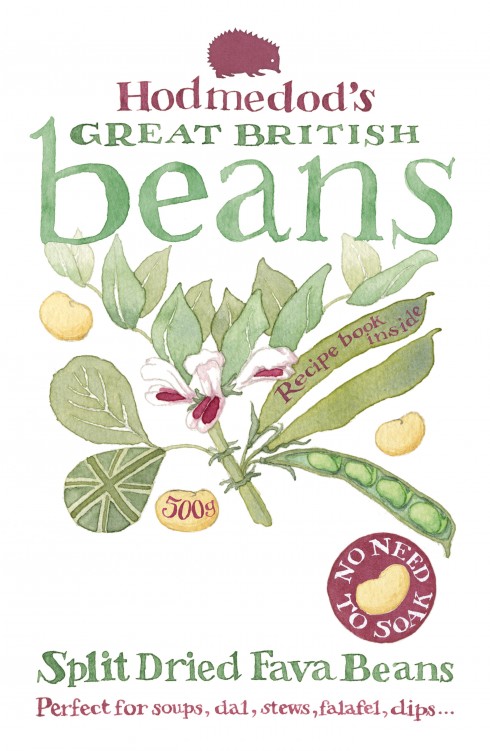

What can you do with them?

You can do almost anything you might choose to do with an ordinary bean. At the moment we have them dried so you can soak them. You might put them in chilis or curries, you an turn them into baked beans if you want to. But we do have an extra thing that might happen which is the beans are decorticated which means the outer skin of the bean is removed and you’re just left with the two halves of the bean. It looks a bit like a very big lentil or a split pea, and that’s quite flexible.

Here are the falafels I made with my Hodmedods beans just before Christmas. By the way, my kids loved them.

You don’t need to soak it overnight, which makes it slightly quicker. You can cook it into dhals, make falafels, you can make an equivalent to hummous, which they eat a lot in North Africa, particularly in Morocco, where it’s called bisara. It’s served either as a dip or a paste, sometimes it’s used as a base for a soup. So you can do quite a lot with them. In Egypt the whole dried beans are used to make something called foul medames which is essentially a bean stew which they have for breakfast. They also have it to break fast during Ramadan. They eat huge quantities of these beans and in fact a large quantity of the beans that we grow for export are sent to Egypt in container ship loads.

The box of beans that you sent to me is beautifully packaged, there’s a little recipe book in there. There’s obviously been a lot of care and attention gone into making it something that will look really nice on the shelf and in people’s kitchens and so on. To what extent are you seeing this as a food crop of the future and what are your commercial plans for them?

I think increasingly there’s a broader awareness that we’re going to have to change our diet in some way over the next 30 or 40 years. There are pressures from population growth, pressures on land. Beans are going to play a part in that as a very low-tech solution to dietary change. There’s a lot of talk about lab-grown meat – in fact there were some articles in the papers over the weekend about all these ‘future foods’, but in fact we’ve got a lot of low-tech solutions to problems like that, and bean protein, which is very tasty and extremely good for you, is one of them.

The big issue is that culturally we’re just out of the habit of eating beans full stop, particularly fava beans, so we found it was really important to make them look as attractive as possible to encourage people to get them home into their kitchens and have a go at using them. We’d like to see it working for local farmers, but it’s early days as yet. The response that we’ve had has been extremely positive.

What kind of infrastructure have you had to put in place to be able to deal with the beans so as they come off the field, what needs to happen to them between this and ending up in your beautiful boxes?

All the infrastructure is there to deal with the beans, but it’s there to deal with the beans for export. All we’ve done really is dip into that process. At the moment, the farmer will grow the beans, they’ll be combined just like wheat is, and then they’re sent up to various grain merchants or factors who deal with the grain and then it’s cleaned, it goes through various screens, then any stones and debris are removed from it and essentially it’s then bagged up.

The problem we’ve had is that because it’s exported in really big quantities, the smallest size that most of these grain dealers can handle is 100 tonnes at a time which is massive, it’s a lot of beans. At the moment we’re working out of those big silos, but from this Autumn we’re hoping to engage more directly with farmers and with smaller scale processes which would allow us to clean in 10 tonne batches. That will also mean that we can source organic beans which at the moment we’re not able to do because we can’t buy 100 tonnes of organic beans.

How are you planning to distribute these? The box that I got, was that just from a small test batch? Are these going to be appearing in shops on the high street near readers soon?

I hope so! At the moment we’re very much in a launch phase, so we’re sending beans out to people like you who we think would be interested and we’d like to thank for being interested and supporting the work over the last couple of years. We’re sending them out to restaurants to have a go with, and we’re also sending them out to wholesalers, people like Suma and Infinity, the traditional wholefood wholesalers who we think will be very interested.

We’ve been talking directly to independent retailers, mostly in East Anglia at the moment, and we’re working with a distribution company who can dispatch them to almost anywhere, so we’re selling them online and people can order them and have them delivered directly to their home.

I cooked some falafels with them, and I cooked a dhal with them and they were absolutely delicious, very easy to cook. My kids didn’t notice the difference, which is always a bit of a winner! I think I didn’t soak them long enough for the dhal, so it was slightly, erm, methane-generating, but I think that’s the case with all beans and pulses generally. You mentioned a story about NASA and flatulence…

That’s right, during the 70s NASA had a dedicated researcher whose particular job was looking at the diet of astronauts and wind. His big concern was that the gases that are produced in space are extremely flammable and potentially very dangerous. They were looking at diets which reduced astronauts’ propensity to fart basically. He did a lot of work on this and identified that there was a percentage of the population who just don’t generate flammable gas, and his big argument was that NASA should be specifically screening and recruiting astronauts based on their propensity to fart.

He didn’t recommend them a diet of fava beans?

The interesting thing about beans is they don’t make you fart that much more. We have an expectation around wind and pulses. The thing that really makes you break wind is eating too much protein. If you have a pulse rich diet and your stomach fauna is used to it, there’s no real difference, you should be absolutely fine.

So ‘Blazing Saddles’ has a lot to answer for…

I think it does, yeah.

In the context of Transition Norwich and East Anglia Food Link and the more concrete steps towards local food resilience which you’ve been working on for a number of years, how important is this, and how replicable might this be in other places? What learnings more generally for Transition can you pull out of your bean experience so far?

The thing that really came out of this was exploring an idea. When you have an idea, and you begin to pick it apart, and find out who locally knows what, you discover all sorts of things. One of the things that was most important that we discovered was that there was an assumption that no-one would want to eat the beans, but no-one had bothered asking anyone whether they wanted to eat the beans.

Until we bought a tonne of beans, much to the hilarity of the local bean merchant who just thought this was the craziest idea he’d heard, and we put them into small bags with a return postcard and we asked people to just have a go with them, see what they thought, and we had a very good response through that.

People may have seen those who were at the Transition Network Conference last year, there were bags of beans for people to take …

That’s right, so I think one of the things is you may feel a bit crazy sometimes when you phone people up with your crazy idea, but that’s never a reason to stop doing it. Sometimes it’s worth pursuing these things. In the context of Transition Norwich and East Anglia Food Link, it is a very small project, there’s no doubt about it, but it has generated a lot of interest outside of the beans themselves. People who heard the story have been very enthused by it and have spoken to Transition groups about the beans in other East Anglian towns.

I went to Stowmarket and was on a panel with Tim Yeo and a few other people and I was there to do the food thing and I talked about the beans and I got a standing ovation which was amazing! It was so different and people were so interested and as always with food people can really understand it because it’s happening in their own kitchen, whereas energy or resource crisis is perhaps slightly harder to engage with.

Presumably there’s business plans for this as an enterprise? Is this something that you feel could be a viable up and running enterprise?

Yeah, we’ve created a new business. It’s no longer part of East Anglia Food Link. It’s called Hodmedod’s which is what you saw on the box. Hodmedods is a local dialect word in Norfolk and Suffolk and it means “hedgehog” or “snail”. Like the bean, the dialect is being forgotten as well, and so we like the idea of reviving a word that’s not being used much either.

It is a small enterprise and we will be not only promoting the beans but we will also be interested in looking at other things that are produced in the UK and have been largely overlooked or forgotten. There are other peas – there are Carlin peas which people from the North will be familiar with on Bonfire Night and on Preston market where they’re still served. There’s another type of pea called a Capucijner pea which is very popular with the Dutch and was developed in the 17th century by the Dutch but initially by the Capuchin monks, that we don’t eat any more…

I thought you were going to say it’s a bean that makes fantastic cappuccinos that would free us from importing coffee beans, but you’re talking about a different derivation?

It’s cappuccino coloured, which is why a cappuccino is called a cappuccino – the same colour as the monks’ robes. There are other things, there’s the bare-meal that’s processed in Shetland and Orkney and in the Highlands, barley flour essentially, which would have been a really important part of the diet in the South West as well, where it’s a bit damp for wheat. All the barley breads disappeared with the railways as grain was exchanged more widely.

It would seem to me that with the whole resurgence of regional foods and exploration of different diets, and cooking culture becoming appreciative of innovation and quality foods it could be just the right time for a revival of these beans that we’ve largely forgotten about.

I think so and it does raise a lot of difficult questions. Obviously we’re growing beans that are exported and they’re exported to countries that want and need them. There’s potential to grow a lot more in the UK, and as a break crop, a crop that comes between cereals in an arable rotation. Beans have increasingly been replaced with things like oil seed rape.

That’s happened because the nitrogen-fixing qualities of the beans aren’t really that important any more as we’ve got lots of synthetic fertilisers. But that is going to change and farming systems need to change. Again, there’s another driver for growing legumes more widely.

I love the fact that there was once a time when the word for “snail” and the word for “hedgehog” was the same word. It must have been rather confusing.

In Berkshire it means “scarecrow”!

The plot thickens…

Well there are all sorts of foods that we are well placed to grow in this country that we don’t grow and we don’t eat for all sorts of cultural reasons. The reason why we don’t eat these beans here is largely cultural, it’s got nothing to do with taste or diet – simply because we fell out of the habit, and I think we should look really hard at what the opportunities are, what other crops there are that we don’t grow that we could be growing for a more diverse agriculture and a broader diet.

*****

Win a packet of Hodmedod’s Beans in our fantastic Transition Culture competition!

Here are 6 bean-related facts. The question is how many of them are untrue (i.e. a number between 0 and 6)? The first 5 correct answers pulled out of the hat will win a box of Hodmedod’s beans. Please email your answer to rob (at) transitionculture.org.

- British folk singer ‘Beans on Toast’, “morphed into a rap/hip-hop artist and after sacking his band on New Year’s Eve he formed a full-on country band for 2010”

- Heinz Baked Beans were first sold in the UK in Fortnum and Masons in 1886 as a luxury food, a tradition they continue to this day, where baked beans are included alongside their usual expensive goods

- Some ancient cults who believed in reincarnation, most notably the monastic followers of Pythagoras, believed that human souls travelled through the stems of bean plants to Hades, where they were then transmogrified for their next lives. They therefore believed it was therefore a sin to eat beans or even walk among bean plants under any circumstances

- The true test of advanced practitioners of the art of Kung Fu is to be able to place a dry kidney bean in their navel, and just by using the focused force of their stomach muscles, project it at the ceiling with such force that it shatters. In a recent court case in Helsinki, a hotel successfully sued a Kung Fu master for “destroying an 18th century moulded ceiling with repeated kidney bean-induced pock-marking”. The case is currently under appeal

- Americans like their baked beans sweeter than the Brits: US baked beans contain 14g of sugar per 16 oz tin as compared to 7g for the British version

- In ancient Rome, so esteemed were legumes that the four leading families took their names from them: Lentullus (lentil), Piso (pea), Cicero (chickpea), and Fabius (fava).

Answer please by Friday 25th January at midday. Good luck. In the meantime, if you’d like to try the beans out, Hodmedod’s are offering readers of Transition Culture a 10% discount on online orders of their beans. Simply use the code ‘TRANSITION10’ when purchasing via their website.

hilary hebron

14 Jan 3:34pm

I was sent this article by the local transition group and find it fascinating. I don’t like fresh broad beans because of the tough outer membrane but would happily use them dried. I would also be interested in growing them myself if they can just be left to dry on the plant. It would be great to have a local alternative to the pulses I use.

josiah Meldrum

14 Jan 5:49pm

Hi Hilary,

Sounds like the beans with the skins removed would suit you perfectly! (And between you and me in most parts of the UK the whole fava beans we have will germinate and grow well in the garden – though we’re not licensed to sell them as seed).

Josiah

Louise Doughty

15 Jan 4:26pm

Very interesting article. I’ve been thinking along the same lines – if I really had to grow all our own food what would we eat. I’ve come to the conclusion that I can’t grow french beans where we live (North Wales, 500 ft up) Runners, peas and broad beans do OK. When I’ve tried french beans for drying I’ve ended up with far more dried beans from the runners that have gone to seed, plus had the fresh grean beans. I’ve been thinking about what they would have had in the middle ages. I knew they had peas but wasn’t sure about broad bean types. I’ve been wondering if it would be possible to use the field beans sold as green manure as beans for dried beans?

Josiah Meldrum

15 Jan 6:04pm

Hi Louise – glad you enjoyed the article.

We’ve been growing fava beans (broad beans) in Britain since the Iron Age – the first archeological evidence is from a site near Glastonbury. In fact until the phaseolus group of beans (your runners, French beans, green beans etc.) were discovered they, along with peas, were all we had (though further south in Europe there were lentils and chick peas too).

Back then beans were pretty much exclusively eaten dried. They were a good storable protein/carb and formed part of our staple diet and they feature in the first recipe book written in English (The Forme of Cury written in around 1390: http://www.greatbritishbeans.co.uk/benes-yfryed/). Over time, and as agriculture, industry and international trade developed, we began eating more meat and dairy products, fava beans and peas became seen as food of the poor (pease porridge hot, pease porridge cold…) and fell out of favour – at the same time the new bean varieties began to arrive (and were higher status by dint of their origin and novelty). At around this time we started eating fava beans green rather than dried.

OK, to answer you’re question more directly:

Fava beans grown for human consumption tend to have been bred to reduced tannins in the bean skin (they’re paler as a result). Modern varieties include Wizard and Fuego – they’re generally smaller and paler than if you dried a broad bean bred to be eaten green.

That said there’s no reason why you shouldn’t grow and eat green manure bean seeds (personally I’d make sure the seed was untreated) – you can eat them green too.

The Real Seed Company stock Wizard field beans: http://www.realseeds.co.uk/broadbeanseed.html

We’re not licensed to sell our beans as seed – but I’m (very) sure they’d grow if you planted them… enter Rob’s competition – you never know you might just win some 🙂

We’re really interested in work being done by Prof. Martin Wolfe at Wakelyns Agroforestry (http://wakelyns.co.uk/) in Suffolk – he’s re-awakening some earlier work on bean and cereal mixes – we’ll blog about it later this year, in the meantime here are a few pictures: http://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.284581034978831.47453.282764081827193&type=3

Runner beans are interesting too – more on them later in the year!!

Thanks and best wishes,

Josiah

Louise Doughty

15 Jan 6:38pm

Wow1 thanks for all the information Josiah. In case I dodn’t win any of your beans I’ll think about ordering them online, I’d love to try them.