14 Nov 2011

The Introduction to ‘The Transition Companion’

This book seeks to answer the question:

“What would it look like if the best responses to peak oil and climate change came not from committees and Acts of Parliament, but from you and me and the people around us?”

It’s a big question, which is why it requires this relatively big book to address it, but I think you’re going to enjoy the pages ahead, and the journey they will take you on. For the first The Transition Handbook, published in 2008, this was pretty much a speculative question, but for this new book we are able to draw from what has, in effect, been a five-year worldwide experiment, an attempt to try to put the Transition idea into practice. I think it is one of the most important social experiments happening anywhere in the world at the moment. I hope that by the end of this book you will agree, that if you aren’t involved you will want to get involved, and if you are already involved, it will affirm, inspire and deepen what you are doing and give you a new way of looking at it.

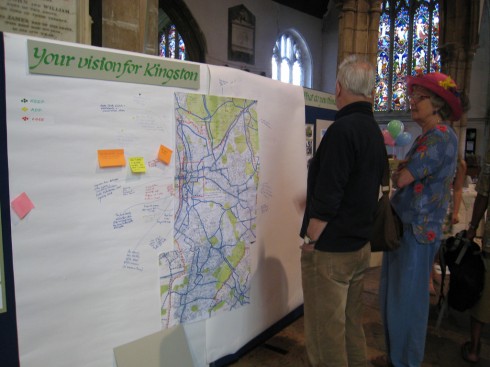

Supported by some simple principles, ingredients and tools – which I’ll introduce you to later – and by a global network of self-organising initiatives, many thousands of people in cities, islands, towns and villages, from the US to New Zealand and from Brazil to Norway, are coming together to ask, “For all those aspects of life that this community needs in order to sustain itself and thrive, how do we significantly rebuild resilience (to mitigate the effects of peak oil and economic contraction) and drastically reduce carbon emissions (to mitigate the effects of climate change)?”

While the overriding cultural response is to duck that question and to pop our heads into the sand of denial, these people are responding with creativity, compassion and a deep commitment. They’re also having fun, lots of it, connecting with people they’d never met before, and together creating something far greater than the sum of its parts. What they’re doing is telling a new story about the place they live and about what it could be like in the future.

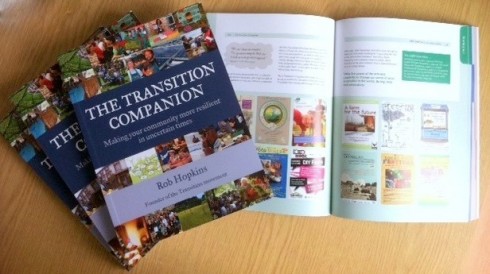

This book is called a ‘Companion’ because that is exactly what it is intended to be. It is a move away from ‘The 12 Steps of Transition’ that has underpinned the work of Transition initiatives up to this point, towards a more holistic, more appropriate model. It will act as a very useful companion as you try to address the questions set out above. It imagines the work involved in transforming the place you live from its current highly vulnerable, nonresilient, oil-dependent state to a resilient, more localised, diverse and nourishing place, as a journey. It is a companion in the sense that it doesn’t tell you which way to go or what your journey will look like, but suggests some of the especially good views along the way, and provides a rough sense of the different types of terrain you will find yourself travelling across. But the journey itself and where you end up – that’s up to you.

The analogy of the journey is a useful one. Throughout history, we have told stories of heroes who undertook extraordinary journeys, which combined an inner and an outer journey. Often they go something like this: a likeable but flawed character (Frodo, Harry Potter, Jason of the Argonauts) is faced with a challenge/problem that seems impossible and for which they feel hopelessly unequipped. They set out on a journey (either literal or metaphorical), overcome the problem and in the process discover they are a hero. To do this they have to go on a journey that transforms them, and on which they are required to take on challenges they feel unprepared for and find new strengths and inner resources. The process of shifting our society on the scale it needs to shift, in the time that we have available, requires a story of such magnitude. At the moment it looks impossible, yet the situation demands courage, commitment and intention from us. In those stories, our heroes don’t have a clear sense of where they are going, but they know which general direction to head in and some of the key stages their journey will need to pass through. This book is designed as the companion for a hero, such as yourself, setting out on such an adventure, one that we need to be embarking on in our millions, and not as solitary heroes but working with others. We can’t do this alone. The idea of the solitary hero can be quite an unhealthy one, and we need to pool our efforts and be heroic together!

Here’s a story of my own, which will hopefully give a flavour of how this journey might unfold. Sometime in 1992, I travelled from Bristol to the Snowdonia National Park with my friend Mark, who had borrowed his mother’s car for the day. We left the city, first passing through suburbia, then through industrial estates, then into the open flat country as we headed to the Severn Bridge. Once in Wales we headed up through the valleys, the landscape becoming more mountainous, before entering a very different landscape of small fields and rolling hills. Finally we entered the national park, with its forests and rocks, as we neared our destination. The reason for our trip was Tir Penrhos Isaf, an emerging permaculture (see page 98) project that had recently set an interesting planning precedent, having successfully argued that their practising permaculture was a valid reason for them to live on their smallholding.

On a damp afternoon with leaden grey skies, we were greeted by Chris and Lynn Dixon, who showed us round the site and told us about what they were doing there over a cup of tea next to their woodstove. Although there was much that impressed me about what they were doing, what was most fascinating to me, and what I took away with me most, was what they weren’t doing. When they had taken on the piece of land, which had been heavily overgrazed by the former owner, they soon fenced off one-third of the site from deer and rabbits to allow it to regenerate naturally. Chris showed us a series of photos taken of the area year after year, showing what then happened. After just three years, the pioneer plants, gorse, broom and bracken, were well established, with young trees emerging. After six years, some substantial trees were established, and the place was starting to look like real woodland.

Most land wants to be forest. If left, grassland will pass through stages, with the arrival of gorse, bracken and brambles, followed by the pioneer trees such as rowan and birch, then the trees that will make up the final woodland, such as oak and hazel. The photos of the evolution of the land showed the process unfolding. Chris felt that the best way to create new woodlands was not to plough the site, plant trees, fit plastic guards to protect them from rabbits, mulch them, apply herbicides to keep the weeds down and then thin the trees to create the desired final spacings; rather, it was just to protect the site from grazing and allow natural regeneration.

I remember Chris and Lynn’s woodland (which is by now a well-established woodland) when I consider the results of the self-organising response to peak oil and climate change that we are starting to see. Are we talking about an imposed, centrally coordinated response that starts with a detailed plan and which takes little account of local culture and topography, or should we enable self-organisation and the emergence of something more specific to the site? While there is a need for support from central government, and the statutory removal of obstacles that stand in the way of communities creating their own responses and initiatives, well organised and inspired community groups can do extraordinary things.

There is another useful analogy in that story too. A journey from one place to another can take a number of different routes, but will usually pass through a series of distinctly different landscapes. You don’t necessarily notice when you leave one and enter another, but there are moments when you realise you are in a very different place. The Transition journey is similar. You find that you move from raising awareness, showing films and trying to interest people, to noticing that you seem to have created an organisation that has different needs from those it had originally, and then later to starting to think about what new businesses and infrastructure your community needs. Each stage is like finding yourself in a distinct landscape. What follows in these pages also tries to capture that aspect of creating Transition.

This book is our best attempt at creating as useful a companion on that journey towards community resilience as possible. It is rich with stories of ordinary people doing extraordinary things, of tried-and-tested tools, as well as some more experimental ones, and offers many of the ingredients you may find you need to create this process where you live.

The way it has been created has embodied this sense of collaboration and creativity. Each of the ‘tools’ and ‘ingredients’ was written in draft and posted to my blog, TransitionCulture.org, as well as on the Transition Network’s site. Comments and feedback were invited. Transition initiatives around the world were invited to send in their stories and photos, which abound in this book. The photoshopped images here were done after I put up a post asking for help with images. Even the title was thought up by Martin Tepper when I put a post on Transition Culture asking for ideas as to what this book should be called.

You will find not just my voice throughout this book, but the voices of many people who are actively trying out these ideas and sharing their experiences. You will hear from Transition trainers, community activists, brewers, bakers, people who have organised a few film screenings in their communities, people who have set up energy companies and local currencies or who have got together to share skills. I am grateful to them all for sharing their insights.

In any journey, there are times when it looks impossible, when we need to rest and recapture why we set out on this mad venture in the first place. There are also times when the view and the journey are so exhilarating that we feel our hearts might burst. Transition initiatives all have very different experiences: they have moments when they can feel the world around them shifting in unimaginable ways, and other moments where it all feels flat and becalmed. This book offers an honest look at the work of Transition initiatives around the world, in the hope that it will inform and inspire you to pick up and run with this approach.

The format for this book arose from wanting to better show how Transition has evolved since it was first suggested, and the insights from the work of many hundreds of initiatives. Initially it was modelled on Christopher Alexander’s ‘Pattern Language’ approach,1 a great inspiration to me over many years. I began, through TransitionCulture.org, to suggest that Transition might make a good pattern language, and to draft some initial patterns, and over time these different aspects of Transition began to be called ‘ingredients’, which people found far more engaging. It then became clear that some of them were more like tools, and so the structure of this book began to come into focus.

Being in the privileged position of hosting conversations and being sent stories, photos, posters, ideas and feedback that have shaped this book has reinforced why all this matters to me. Transition has grown up very fast within just four years into a rich, deep movement that has developed a unique approach. I will speculate at the end of the book as to where I imagine it might go from here, but one of the qualities I hope will come through in this book is Transition’s rigour. In some ways it is an appeal to the environmental movement to get serious about creating a new more localised economy, to create projects and infrastructure that are economically viable, and to engage rigorously with these issues.

It also, I hope, provides a context. You may be helping with a small project: a school vegetable garden, an allotment, the community bus, a community group, or setting up a website. This book aims to set out how all of this might fit together in a spirit of not waiting for permission but just getting on with it, being part of the whole; part of a historic process of rethinking how our communities, our economy and many aspects of our daily lives work. As our economies wobble and contract, the oil price becomes increasingly volatile and the climate breaks record after record, there is no avoiding the fact that now is the time and we are the ones to do this. We may feel like Harry Potter in the cupboard under the stairs, unequipped to even start on this journey, but hopefully this companion will inspire a sense of heroism and an opportunity. We can do this. As my friend Chris Johnstone says, “life is a series of things we are not quite ready for”.

I remember once reading online about a young couple in the US who built themselves a strawbale house. When they got married, they invited all their family and friends and had a clay plastering party. Everyone came along, ate, danced, drank, got filthy, and plastered the inside of their house. “What we love most about our house”, the newly weds said, “is that it has been patted all over by all the people we love.” This book is very similar. It has been patted all over by many hundreds of people who have as much day-to-day experience of Transition as I do, and it is infinitely the better for it. My deepest gratitude to them all and to the amazing team at Transition Network, who support the ongoing spread of Transition. Enjoy the journey.

You can order ‘The Transition Companion: making your community more resilient in uncertain times’ here.

Bart Anderson

17 Nov 12:38am

Available in the US from Chelsea Green:

http://www.chelseagreen.com/bookstore/item/the_transition_companion:paperback