30 Nov 2009

‘How We Used to Live’: bringing Transition and oral history together

We had a great event last week in Totnes, called ‘How We Used to Live’, which explored the most recent period in history when the town had a more localised economy and less energy than it does today. It was built on the oral history work that I have been doing, which will feature in the Totnes EDAP when it comes out. The evening featured Barrington Weekes from the wonderful Totnes Image Bank and Rural Archive, and four of the people I interviewed. Two of them, Douglas Matthews and Ian Slatter, have since passed away, and the evening was dedicated to their memory.

We had a great event last week in Totnes, called ‘How We Used to Live’, which explored the most recent period in history when the town had a more localised economy and less energy than it does today. It was built on the oral history work that I have been doing, which will feature in the Totnes EDAP when it comes out. The evening featured Barrington Weekes from the wonderful Totnes Image Bank and Rural Archive, and four of the people I interviewed. Two of them, Douglas Matthews and Ian Slatter, have since passed away, and the evening was dedicated to their memory.

It was divided into 5 parts, food, shopping, energy, transport and the world of work. For each, Barrington showed a series of slides from the Image Bank on the subject, and then I invited each of the four interviewees to talk about their memories of each. Then anyone else in the audience who had memories of the time was invited to contribute, and then anyone in the audience could ask the ‘elders’ questions.

The first part, food, looked at how food was produced, from allotments and back gardens, to urban market gardens and to the farms that surrounded the town. People talked of the culture around food at that time, how the generation that lived through the war never wasted any food, and that that was the culture they grew up in. David Heath, son of George Heath who ran the largest urban market garden in Totnes, talked about the garden and what an amazing place it was to go to work, in spite of being very hard work. Vera Harvey talked about her father who worked on the railways and who had two allotments at some distance from Totnes, and whose work involved regularly walking the railway lines, and who often returned with rabbits he had caught, or with turnips from the fields.

The first part, food, looked at how food was produced, from allotments and back gardens, to urban market gardens and to the farms that surrounded the town. People talked of the culture around food at that time, how the generation that lived through the war never wasted any food, and that that was the culture they grew up in. David Heath, son of George Heath who ran the largest urban market garden in Totnes, talked about the garden and what an amazing place it was to go to work, in spite of being very hard work. Vera Harvey talked about her father who worked on the railways and who had two allotments at some distance from Totnes, and whose work involved regularly walking the railway lines, and who often returned with rabbits he had caught, or with turnips from the fields.

John Watson, who founded Riverford Organic Farm, talked about starting farming just after the war, and how for him, the greatest inventions of the last cenury were hydraulics and the combine harvester. I quoted his friend, Douglas Matthews, who recently passed away aged 102;

“Looking back, practically all our food came from this area. We had a couple of house pigs that ate the rubbish. A local chap would come by, cut their throats and cut them up, and make bacon and hams. We used to preserve it in saltpetre, the wives would make a salt solution and baste it every 2 days, then it was put up on hooks in the dairy to dry. I still have the hooks out there now. I suppose we might have had an orange on very special occasions. Our main meal was lunch, not supper, if the husband worked at home. Evening meals were a professionals’ thing. Lunch was normally roast beef, mutton, hot or cold. Hot or cold chicken, stews, potatoes and veg, peas and beans, potatoes baked or boiled. We ate meat every day, hot or cold, depending on how the husband and wife were getting on! For tea we had bread and butter, jam and cream. For breakfast it was bacon and eggs. Supper was just a snack meal, bits and pieces of what you liked. For fruit we had apples, pears and plums. Apples could be kept all year round. They were kept in a cellar under the house. Certain kinds of pears could be kept. We had greengages and plums; we usually made those into jams”.

Then shopping. The slides showed a town with lots of shops that no longer exist, when the town was a town that actually sold everything you could want, several hardware shops, tailors, a wealth of food shops, even a shop selling agricultural machinery. There were slides of the first supermarket to open in the town, and one audience member who worked there as a girl talked about how they had to weigh potatoes out into bags, rather different to the supermarkets of today! I read a quote from Muriel Langford who I interviewed, about a trip to the shops in the 1940s..

Then shopping. The slides showed a town with lots of shops that no longer exist, when the town was a town that actually sold everything you could want, several hardware shops, tailors, a wealth of food shops, even a shop selling agricultural machinery. There were slides of the first supermarket to open in the town, and one audience member who worked there as a girl talked about how they had to weigh potatoes out into bags, rather different to the supermarkets of today! I read a quote from Muriel Langford who I interviewed, about a trip to the shops in the 1940s..

“I used to go to the grocers and I could sit down, lovely. They’d go through your list and say, “yes, yes, we’ve some new whatever it is, would you like to taste some?” You’d have a little snippet of cheese or something, “great, yes, we’ll have that”. “Now we’ve got a tin of broken biscuits, but they’re not too bad (half price you see), would you like them?” As soon as you put a biscuit in your mouth it’s broken isn’t it! Then they’d say “now Mrs. Langford, you’re going to the butchers, yes, yes, and going to get some fish? Yes, yes, and paraffin? Yes, yes… and they used to say to me now bring any parcels in, we’ll put it in the box with your groceries and bring the lot up for you. And they did. They’d come and deliver and you’d go through it and say that’s fine and would you like a cup of tea….”

For many, the move away from the dynamic, more self sufficient economy of that time to the supermarket-focused economy of today has not been entirely beneficial. This was summed up best by interviewee Ken Gill, who said, in the interview I did with him;

…it has been progress of a sort, or has it? I’m not sure. We lost something we will never be able to regain. The loss of a lot of small shops has been hard, although we have replaced them with what we might call ‘slightly unusual shops’… We’ve lost the dairies, the independent grocers, although we have retained a good selection of butchers and some good cheese and fish shops. When you consider what we used to have….”

In his slides about energy, Barrington looked at how the town used to be powered by town gas, coal brought from South Wales by boat was gassified in two gassifiers, producing the gas the town used for cooking and, until the 1950s, for street lighting. He also showed pictures of the first petrol pumps in the town. Alan Langmaid talked about how freezing cold everywhere was at that time, and how the idea that he could, as he did that evening, walk down Totnes High Street in a tshirt in late November, would have been ridiculous.

In his slides about energy, Barrington looked at how the town used to be powered by town gas, coal brought from South Wales by boat was gassified in two gassifiers, producing the gas the town used for cooking and, until the 1950s, for street lighting. He also showed pictures of the first petrol pumps in the town. Alan Langmaid talked about how freezing cold everywhere was at that time, and how the idea that he could, as he did that evening, walk down Totnes High Street in a tshirt in late November, would have been ridiculous.

He talked about his grandmother, with whom he and his mother lived, keenly moving out of an old house that was a converted cider press. “She just wanted modern. She wanted electric fires, electric cookers, electric everything. She wanted automatic this, that and everything. So we moved, at my grandmother’s insistence, from this wonderful rambling old building…. to a brand new house, typical of its time. Wooden framed, single glazed windows, open fire for a chimney which she quickly replaced with an electric fire, “I’m not having any more of that dirty coal business”. The winters were actually colder than the previous house. You’d wake up in the morning, and your breath would have condensed on the window, frozen on the inside. Inside it was cold, outside it was cold. Eventually my mother paid for an electric fire to be put in so you could reach out of the bed and turn it on. Electricity was cheap in those days”.

Vera Harvey talked about washing clothes, how as a girl she had to help her grandmother do the washing in the wash house in the yard, whatever the weather, often still working by candlelight late into the evening. She remembered, once the first washing machines became available, telling herself ‘I’m not going out in that wash house like Gran!’ In the 1950s, our first washing machine had a wringer on top. I remember when we used the washhouse, being out there with my Gran, and it was snowing, getting deeper and deeper, saying ‘Gran! We can’t stay out here!’. People worked so hard in those days”.

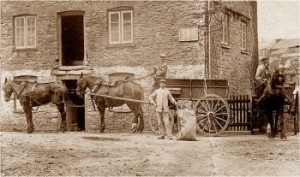

The slides on transport started with a picture of the horsedrawn stagecoach which was how people got to the town before the trains and the internal combustion engine took over. They included some amazing slides from when Totnes High Street was two-way, amazing to imagine now, one in particular showing a bus and a tractor towing a huge oak tree trying to pass each other in the part of the High Street known (see right), appropriately, as The Narrows. There were images of the first cars, the first trains, and the interviewees recalled their first cars.

The slides on transport started with a picture of the horsedrawn stagecoach which was how people got to the town before the trains and the internal combustion engine took over. They included some amazing slides from when Totnes High Street was two-way, amazing to imagine now, one in particular showing a bus and a tractor towing a huge oak tree trying to pass each other in the part of the High Street known (see right), appropriately, as The Narrows. There were images of the first cars, the first trains, and the interviewees recalled their first cars.

I quoted Val Price, who I had interviewed but who had been unable to make the evening. She had recalled how her father had bought a car in late 1952, and lovingly built a garage to keep it in. However, she recalls that he rarely used it, never using it to pick her up from school, and never taking it out during the week, given that everything he needed was within walking distance. It was only ever used on weekends, for trips to visit relatives. Arthur French, a member of the audience, noted how the age at which people first got cars has fallen during his lifetime. He said that he got his first car at 40, his sons at 25, and nowadays people start driving at 17.

The final section looked at work and livelihoods. Barrington’s images introduced an economy very different to the Totnes of today. The Totnes of 2009 has very little in terms of manufacturing, and has lost most of its main employers over the past few years. In the 40s and 50s, things were very different. We were introduced to Reeves Timber Yard, Harris’ Bacon factory, the markets, potters, shoemakers, the milk processing plant, and various other local employers. Alan Langmaid talked about working for the Totnes Times when he left school, and about the work ethic of the older generation, who worked from dawn to dusk, and also how incredibly strong they were.

One of the last images was of the town carter, a man with a sort of souper-up go cart, who served as the DHL of his time, running errands and deliveries around town in a handpulled cart. The photo showed him as a young man in the 1920s, but several of the older members of the audience remembered him still being active with his cart in the 1960s. David Heath remembered a particularly horrible grating noise the cart made as it flew down the High Street, and Alan Langmaid, who now runs Totnes Museum, noted that his cart is still in Totnes Museum, and is set to be part of an exhibition next year.

One of the images that most stuck with me was of the last working flour mill in Totnes (see right), which shut some time ago. What is important about these oral histories isn’t that it allows us to romanticise some former halcyon time where everything was rosy and jolly policemen smiled at everybody from the street corners, but it reconnects us with the infrastructure that a more localised economy needs. It is a reminder of how easy it is to get rid of things, but how hard it is then to put them back.

One of the images that most stuck with me was of the last working flour mill in Totnes (see right), which shut some time ago. What is important about these oral histories isn’t that it allows us to romanticise some former halcyon time where everything was rosy and jolly policemen smiled at everybody from the street corners, but it reconnects us with the infrastructure that a more localised economy needs. It is a reminder of how easy it is to get rid of things, but how hard it is then to put them back.

Shutting down an uneconomic flour mill is easy enough, the person who ran it was probably close to retirement anyway, and it was no doubt not economically viable. However, putting a new one in from scratch today would be a far, far greater task. Finding people with the skills to make good flour, to run a mill. Finding the machinery, a suitable space, good sites with sufficient water power to run the mill. Not easy.

This event was a fascinating look at the history of the town, still near enough for us to be able to draw on first hand memories of it, but far enough away to feel like another world. Thus far, TTT has focused just on looking forward, to visioning what a post-oil Totnes might be like…. this was the first attempt to look back, to try and capture how the place functioned before liberal lashings of cheap oil fundamentally altered how the place functions. For those I spoke to after the event, all had found it a fascinating immersion in what a pre-globalisation Totnes looked, smelt, sounded and felt like. While one can read history books, and look at the facts and figures around that time, it is hearing the stories, the first hand accounts, and the anecdotes of those who were there, that truly brings it alive.

Brad K.

30 Nov 12:40pm

I wonder just how much we romanticize the difficulty of re-creating historical skills and crafts.

Take the flour mill. I imagine that the first step is to find someone interested in milling flour. The second is to find someone that knows how, knows what the important parts of the process are, and what equipment and accessories are important. Then learn.

One asset we have today cannot be over-emphasized – information. Back when flour mills were a local necessity, milling was simple to learn – every region had one or three. You hiked to the nearest mill, hung about and hopefully worked there, learning the trade. You learned the equipment, figured out how to locate and procure what was needed, from a spot of ground to a building and other needs.

Today what might have taken years of preparation, half a lifetime unless learned growing at your father’s knee (half a lifetime!), can be done in a couple of years. Books, videos, even the remembrances of those from previous years, are available – once you find someone interested in milling.

Book learning is not the same as apprenticing. No two people read a book and get the same information, mistakes must still be made, and rectified, and any trade or craft is still a half lifetime in the learning. But today thousands have access to the basic background and information that one person or one craftsman had to offer a handful of apprentices, back in the day.

The Internet, newspapers and magazines, libraries and bookstores enable communications for questions, for recommendations, and for swapping stories that happen to share insights, values, and inspiration.

With care, we might even be able to preserve some of the best of today’s and yesterday’s knowledge.

Josef Davies-Coates

1 Dec 8:14pm

Hydraulics are used a great deal in the incredibly inspiring project Open Source Ecology who are working to design and build the a Resilient Communities Construction Set! 🙂

I’d encourage everyone to join me in becoming a true fan by contributing $10 a month to help fund their efforts! 🙂

Andy in Germany

3 Dec 9:10am

Interesting stuff. What encourages me is that the world these pictures show isn’t the post-apocalyptic wasteland often conjured up by many people trying to keep the status quo going.

Germany isn’t as far along this process as the UK. We’ve lost a lot of local businesses, but even in our village we have two carpenters and two housebuilders, two butchers, a general food shop, and three bakers (although they are part of a chain, it’s a local chain.) We do have one supermarket.

And we have a flour mill in the valley, albeit in the next town.