20 Sep 2012

Day one at the Degrowth conference in Venice: “When we reach the bottom of this current crisis, the things that at the moment seem like a Utopia will in fact seem very realistic”

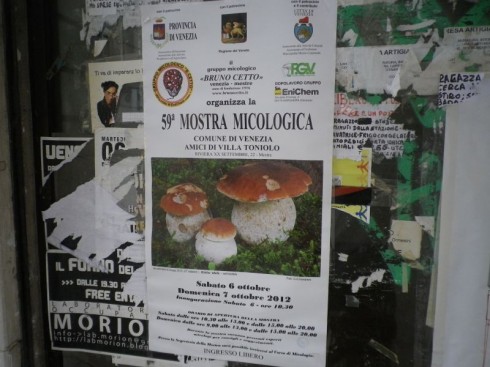

I’m in Venice at the 2012 Degrowth conference. I’ve never been to Venice before, it is really quite an extraordinary place. Even in the rain. It took me 17 bleary hours on various trains, but that was time well spent. This is the third Degrowth conference, and it has brought together people from far and wide, with its theme of ‘The Great Transition: degrowth as a passage of civilisation’. The conference started this afternoon, in the Teatro Malibran, a beautiful old theatre.

It began with opening remarks from the Mayor of Venice, the Rector of the University Institute of Architecture of Venezia and the Rector of the University of Udine, welcoming people to the city and to the conference. Then there was a brief talk by two people (whose names escape me) from Montreal, who will be hosting the next DeGrowth conference in 2 years time, a bit like how the Olympic Flame is handed to whoever will be hosting it next time. Then we were into the main speakers.

My spoken Italian is pretty good, but not as good as I thought it was, and I had expected to be able to follow more of the talks than I was actually able to. So apologies for the fact that it wasn’t until halfway through the first of the main speakers that I actually got hold of a headset and was able to follow it fully.

That first speaker was Serge Latouche, Professor Emeritus of Economics at Universite d’Orsay, near Paris. What follows is based on my notes, so any mistakes are entirely mine. Europeans, he said, have to be brave, and have the courage to abandon the Euro. He described the Euro as being a “monstrosity” from an intellectual point of view. Money should be at our service. Free competition is a fraud, and protectionism protects no-one but multinational corporations. What we need is a kind of protectionism that protects the poor and the environment.

We need also to get away from the idea of liberalisation. The Troika are playing this massacre at the European level. We need to write off debt, default on our debts, then we can escape this terrible hell, and move to a society without growth. We need to reject both austerity AND growth, we have to escape the imperialism of growth. History is littered with governments and nations that defaulted on their debts, and the world didn’t come to an end. Our first objective has to be to solve the most tragic problem, that of growth. Local initiatives should be protected.

We need to go back to organic farming, as current practices are terrible. We need to learn to do without pesticides and produce food in a different way. We must reconvert energy. We are approaching the end of cheap oil, and we need new sources, not shale gas and nuclear, but truly renewable energy. We need also to cut working times, working less to live better and to have more time to dream and to live. Words are easy, deeds harder. When we reach the bottom of this current crisis, the things that at the moment seem like a Utopia will in fact seem very realistic.

The next speaker was Helena Norberg Hodge from the International Society for Ecology and Culture. She said that for her, Degrowth and the Economics of Happiness are the same thing. Although there are things that offer encouragement over the last 4 years, this is still a huge crisis. It is useful to keep in mind the global picture. Through working with countries around the world, this picture has become clear.

Globalisation has been in fact a deregulation of finance, removing the rules that protect society from big business. She read recently that the Economist magazine was founded in order to fight protectionism. ‘Protectionism’ is about protecting people and the environment, and governments oppose the idea. This concept is found in books, on TV, it is the dominant system, a view that tears apart society and the living world. It has undermined our democracy. The EU exists to serve the needs of big business and to reduce diversity.

Growth has come to equal trade, and trade to equal global trade. The distances between trading nations grows greater and greater. If tomorrow, people sat down to a breakfast produced entirely in their region, no money would flow to corporations, but lots would flow to local farmers and growers, and we would have clean, safe, healthy food. Now, food from far away is cheaper than local food. Organic food is more expensive because of the way subsidies skew the system towards industrial agriculture. Localism is not about ending trade and tourism.

One of the biggest myths of the past 10 years is that the best way to end Third World debt is to give microcredit. No-one stopped to think that this debt, accrued by women in rural communities, moved economies away from subsistence to being able to buy consumer goods, driven by the power of satellite TV. This pressure to consume is based on the idea that young people have to conform: the right jeans, right shoes, or they won’t be loved. Every child longs to be loved, to feel approval. Consumer culture has perverted this so that young people won’t get approval without these things. But it has created the opposite, leading to alienation and loneliness.

Localisation is happening, it’s not just an idea. It’s about decommercialisation and rebuilding relationships between producers and consumers. The movement for local food is the most powerful. Urban farmers, CSAs, school gardens etc. What we need to do is to bring the economy home. We also need local business alliances, where local businesses link up to support each other. What we need to grow is the number of businesses, not the size of them. While industrial production of rubber balls makes sense, for apples it doesn’t.

Local food movement is exploding the myth that large agriculture is needed to feed the world. Local agriculture can feed more people and produce more food with a diversity of crops. Localisation has now gained such momentum that the New York Times recently spoke of ‘localising the future’. Time magazine has also spoken of ‘locanomics’, driven by the rising cost of oil and of labour costs in China.

The Transition movement is one of the fastest growing movements in recent times, but another far bigger but also very important is Via Campesina. This opposes globalisation and is now the largest social movement in the world. Healthy food equals healthy soil. That link is deep and has been with us since the beginning of time, it’s how we evolved. It is, she concluded, the economics of happiness.

Next was Veronika Bennholdt-Thomsen of University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences in Wien. The theme of her talk was subsistence. Transition, she said, is achieved by small steps. She began with a fairy tale. It’s 2099, and humans are getting ready to celebrate the turn of the third millennium. People are happy, they live in a time of peace. There is no famine, no war. People have confirmed their commitment to the future and to happiness. People now live in small cities and village surrounded by vegetable gardens, flowers, woods, which are owned by communities.

Fountains, lakes and rivers are treated live revered grannies. Everyone is convinced that every area and every human being can offer a lot. It is a time of happiness. The main economy is people making gifts. People prepare songs for the celebration, some have gone on pilgrimage. Many more move towards Venice where in 2012 the foundation was laid for the Great Transition towards a happy society.

If we want peace, we have to resolve the economic crisis. The principle of growth has invaded the brains and hearts of people. We need to decolonise the culture that puts economics at the centre. My contribution is the perspective of subsistence, highlighting the economics of subsistence. My aim is to eliminate the idea that we get all we need to live well from a consumer society. Subsistence is not ‘under-development’. After World War 2, racism took new roots, being ‘underdeveloped’ becoming seen as being inferior.

Let us adopt subsistence. What do we need to live well and be satisfied without always needing more. In subsistence, satisfaction comes from civil society, not from governments or corporations. She has noticed a change in Germany in recent years. When this idea was raised, until recently people saw subsistence as something for just the 3rd World, about going back to live in caves. Now it is a real topic for discussion.

Transition initiatives are now underway in Germany, Switzerland and Austria. Another important movement is urban gardening. Let’s access as much urban land as we can and cultivate it. The ecovillage movement has also been promoting subsistence for over 30 years. In Bidefeld (where she lives) we have been preparing a meal once a week for whoever wants to come. People who depend on food banks are invited. Also people who would otherwise be eating alone. Loneliness is one of the worst things in our society.

Some people say that this isn’t politics, it won’t make an difference. Or “it’s only for food, nothing to do with economics”. This is true, it’s not politics. However, in other ways it is, moving away from being Homo economicus, and this shift is necessary to create degrowth. It doesn’t depend on money. It relies on groups of friends.

Growth supports one single culture. The United Nations’ Millenium Goals intend to eradicate poverty and cut people suffering from hunger by half. However this has already failed and hunger in the world is rising and will continue to do so. So, I would like to ask, you, which is the most realistic, my fairy tale at the start of this talk, or the United Nations Millenium Goals?

I was then the final speaker, and for my talk I remembered to turn on my recording thing, so here it is.

When the evening was over I walked back to where I am staying through the Venice streets at night. Beautiful. Tomorrow is workshops with some really interesting-looking topics. I’ll do my best to take some useful notes…

Amanda

20 Sep 9:07am

Sounds fantastic and am only 4 hours away from Venice in N Italy – would have loved to have been there. Via Campesina sounds interesting.

A

Craig Ambrose

20 Sep 9:17am

What a wonderful sounding conference, and so great to have the audio from your talk to listen to this evening.

Geoff Garver

20 Sep 10:30am

Great talk last evening about Transition Towns and how they tie in with degrowth, Rob! Just a small adjustment, as one of the two Canadians who talked about the Montreal degrowth conference. It happened in May 2012, so it is not something that is going to take place in the future – although I hope degrowth will continue to take a hold in the Americas, with more discussions and gatherings about it. For more about the Montreal International Conference on Degrowth in the Americas, go to montreal.degrowth.org – lots of papers, reports and videos about the conference.

Rob Hopkins

20 Sep 11:32pm

Thanks Greg! Oops. The dangers of having no translation and thinking you know what’s going on! Thanks for pointing that out. Thanks for the link too, I’m sure people will find that very useful.

Erik Buitenhuis

22 Sep 10:17pm

As always a very well structured and engaging talk. I wonder how well connected we cultural creatives / permaculturists are, how many people raised their hands at the beginning when you asked whether they knew of a Transition initiative near them?

Peter Brandis

25 Sep 2:03pm

Thx for the mention to Veronika Bennholdt-Thomsen – I am examining her work and her book at present – and feel that it is a rich piece of work – relevant to Transition and especially permaculture. I did find your summaries a bit difficult to follow – as it was hard to work out if it was the speakers comments or your that I was reading. Perhaps it was all speaker comments?

jacqueline fletcher

29 Sep 8:11am

I live in France and Serge Latouche is my all time favourite French economist. He’s written a lot of books about de-growth and the ‘exit’ from consumer society. One of them was translated into English as Farewell to Growth in 2009 (Polity Press). I wish more could be translated. I can translate them if anyone knows of a publisher who would publish them. Language shouldn’t be a barrier to sharing ideas.