22 Nov 2011

Community resilience, Transition, and why government thinking needs both

After my talk in Norwich last week, I met a local authority emergency planner, who said that he had found the talk, and the Transition take on resilience, very illuminating. He pointed me in the direction of the latest ‘Strategic National Framework on Community Resilience’, the latest “national statement for how individual and community resilience can work”, published by the Cabinet Office in March of this year. It is a fascinating document, and is indeed the first official government document on community resilience that refers explicitly to the Transition movement, and as such deserves a post reflecting on it. It also offers a tantalising glimpse into what a government response to peak oil, climate change and economic contraction might look like if anyone had the imagination to create one.

After my talk in Norwich last week, I met a local authority emergency planner, who said that he had found the talk, and the Transition take on resilience, very illuminating. He pointed me in the direction of the latest ‘Strategic National Framework on Community Resilience’, the latest “national statement for how individual and community resilience can work”, published by the Cabinet Office in March of this year. It is a fascinating document, and is indeed the first official government document on community resilience that refers explicitly to the Transition movement, and as such deserves a post reflecting on it. It also offers a tantalising glimpse into what a government response to peak oil, climate change and economic contraction might look like if anyone had the imagination to create one.

‘Resilient to what?’

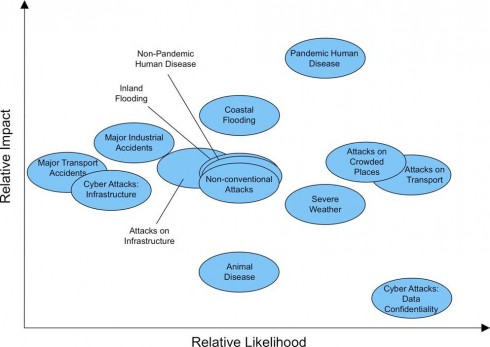

The first point of call in any discussion about resilience is ‘resilient to what?’ Fascinatingly, this document states that, when it comes to community resilience, “community resilience work should prepare for all relevant hazards and threats, prioritised as the community considers appropriate”. So, rather than being determined from above, their suggestion is that it is for communities themselves to determine what they see as the greatest risks. However, they do also point to the National Risk Register for civil emergencies, which illustrates what it regards as being the key threats communities need to build resilience to in the following graphic:

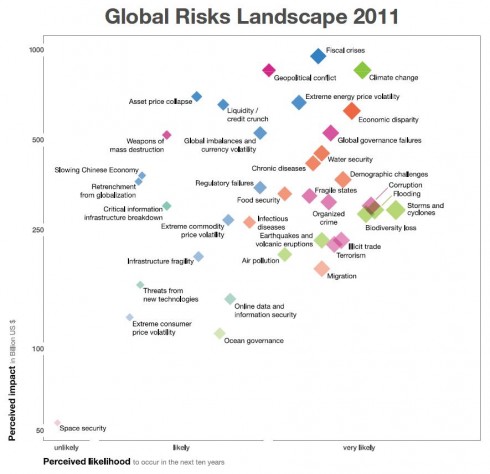

However, in terms of a recognition of the risks that are most pressing and likely, this chart clearly contrasts with that produced earlier this year by the World Economic Forum, which puts all of the above as way below what it regards as the 4 greatest risks, in terms of likelihood of occurring within the next 10 years and in terms of perceived economic impact: climate change, ‘energy price volatility’, fiscal crises and economic disparity. None of these even make it into the National Risk Register’s table. A friend of mine recently attended an event about emergency preparedness in Brussels which explored possible scenarios that could emerge from a collapse of the European economy. The scenarios presented left him quite traumatised, yet in comparison, the Framework’s scenarios seem pretty tame, and somewhat more ephemeral in comparison!

Yet the Strategic Framework document, if read with the thought in mind that it is referring to resilience to peak oil, climate change, and economic contraction, actually reads in places like something Transition Network might have produced (as we will see). That certainly took me by surprise.

Defining resilience

Throughout the document, resilience is defined as:

“The capacity of an individual, community or system to adapt in order to sustain an acceptable level of function, structure, and identity”

…and community resilience as:

“Communities and individuals harnessing local resources and expertise to help themselves in an emergency, in a way that complements the response of the emergency services.”

It states that its role is to “invite individuals and communities to prepare themselves in the event of an emergency”, but also makes it very clear that, amazingly, “there is no dedicated funding for the programme”. It restates the commitment, central to the Big Society concept, “to reduce the barriers which prevent people from being able to help themselves and to become less resilient to shocks”. Like the Big Society, it assumes that communities can self-organise around community resilience with no resource for any of their work. They do acknowledge Transition as one of the few community-led initiatives actually looking at resilience, and which is actually manage to inspire people to action around the theme of resilience:

It states that its role is to “invite individuals and communities to prepare themselves in the event of an emergency”, but also makes it very clear that, amazingly, “there is no dedicated funding for the programme”. It restates the commitment, central to the Big Society concept, “to reduce the barriers which prevent people from being able to help themselves and to become less resilient to shocks”. Like the Big Society, it assumes that communities can self-organise around community resilience with no resource for any of their work. They do acknowledge Transition as one of the few community-led initiatives actually looking at resilience, and which is actually manage to inspire people to action around the theme of resilience:

“Resilience is also a key part of other kinds of community activity, for example the Transition Towns movement and the Greening Campaign where resilience is a longer term ambition for communities looking to adapt to climate change”

However, this does rather miss the point, suggesting that they are addressing “longer term” issues like climate change. It is true that many of the impacts of climate change, and peak oil, and economic contraction, are longer term, but many are not, and indeed the window of time within which to profoundly modify our ways of doing things certainly is not. And as the World Economic Forum argues, they look likely to be the most significant over the next 10 years. That looks pretty short term to me.

The aims it sets out rather fascinatingly read like the aims of Transition Network!

- increase individual, family and community resilience against all threats and hazards;

- support and enable existing community resilience, and expand and grow these successful models of community resilience in other areas;

- remove the barriers which inhibit or prevent participation in community resilience at a local level;

- support effective dialogue between the community and the practitioners supporting them;

- raise awareness and understanding of risk and the local emergency response capability in order to motivate and sustain self resilience;

- provide tools to allow communities and individuals to articulate the benefits of emergency preparedness to the wider community;

- and provide a shared framework to support cross-sector activity at all levels in a way that ensures sufficient flexibility to make community

With such a clear recognition in a government publication that these ought to be key aims in terms of resilience, one would imagine that the work the Transition movement has been doing over the past 5 years, and the practical initiatives it has led to the ground, would have deserved more than one sentence in this publication.

Shifting the thinking slightly: a Transition take on resilience

The perspective on resilience that the Transition approach brings to this discussion would be useful to explore in more detail here. Rather than making do with the definition set out in this report, (“the capacity of an individual, community or system to adapt in order to sustain an acceptable level of function, structure, and identity”), Transition adds another layer onto that, of arguing that community resilience, if done properly, could be about much more than just being able to ‘sustain an acceptable level of function, structure and identity’. Rather, it argues, it offers the potential for stimulating the kind of economic revival at the local level that is so keenly sought at the moment. A more resilient economy could be a more viable, entrepreneurial, biodiverse, flourishing economy. As I argue in ‘The Transition Companion’:

“making a community more resilient, if viewed as the opportunity for an economic and social renaissance, for a new culture of enterprise and reskilling, should lead to a healthier and happier community while reducing its vulnerability to risk and uncertainty …. resilience is reframed as a historic opportunity for a far-reaching rethink”.

For example, setting up a food hub to create viable links between local producers and consumers, adding infrastructure for local food processing (such as Transition Norwich’s new community mill, or Portobello Transition Town’s new organic market, see right), creating urban food production and identifying new sites for that, mapping local foodsheds and supporting small farmers, setting up Community Supported Agriculture systems, all build food resilience and a community’s ability to respond in an emergency (much more than food stockpiles), but also have very beneficial impacts on the local economy too. These kinds of things would have helped greatly in building resilience to, for example, the lorry drivers’ dispute of 2000 when food supplies in shops became dangerously low.

Likewise, setting up community energy systems that are in community ownership can also put in place infrastructure that would also be beneficial in terms of an acute emergency, while also boosting local economies. It is for this reason that Transition Network and others are arguing for a Community Tariff to emerge from the Feed-in-Tariff review. With Greg Barker, Energy and Climate Change Minister, recently tweeting that “Under Labours #FiTs, there is no way 2 differentiate btwn community projects + a hedgefund. We will change + create a new community tariff”, things look hopeful. This could have a huge impact.

The document clearly states the principle that “the Government role is to support, empower and facilitate; ownership should always be retained by communities who have chosen to get involved in this work”. This feels like an acknowledgement of Transition’s role of not waiting for permission but getting started building community resilience from the bottom up. That’s not to say that a bit of more formal support wouldn’t be a good thing from time to time to actually accelerate the creativity that the Transition process can unleash!

Likewise, the building of social capital, creating a stronger sense of community and sense of optimism about that community’s ability to respond, as was observed through Transition Town Totnes’ ‘Transition Streets’ programme, is a key aspect of emergency preparedness. Local currencies, such as the Brixton Pound (see left) and the forthcoming Bristol Pound, can be a powerful catalyst for rebuilding the connections between local businesses that a resilient community will need, and can focus thought on how local traders can best support and trade between each other. Whether an emergency happens in 6 months or in 6 years, the additional resilience they will have created will still have a valuable impact.

Likewise, the building of social capital, creating a stronger sense of community and sense of optimism about that community’s ability to respond, as was observed through Transition Town Totnes’ ‘Transition Streets’ programme, is a key aspect of emergency preparedness. Local currencies, such as the Brixton Pound (see left) and the forthcoming Bristol Pound, can be a powerful catalyst for rebuilding the connections between local businesses that a resilient community will need, and can focus thought on how local traders can best support and trade between each other. Whether an emergency happens in 6 months or in 6 years, the additional resilience they will have created will still have a valuable impact.

Given the current government focus on localism, enterprise, decentralisation and resilience, I would argue that reframing community resilience as being about much more than how it is presented in this document would have huge benefits across the board. It would focus the mind on what kind of new infrastructure would be needed, what new business opportunities emerge, and add an additional layer to the current obsession with recreating growth at all costs. Does new housing which is not both built to very high standards of energy efficiency and built using local materials represent a huge missed opportunity, and actually reduce community resilience? Is the continued undermining of local food economies through the enforced imposition of supermarkets ultimately self-defeating from a resilience perspective (as New Economics Foundation’s ‘Plugging the Leaks’ work suggests)? Let’s have a bit of ‘joined-up thinking’ here please.

Certainly the Transition take on resilience is at odds with the one set out in this Framework, and to that set out in most academic literature on resilience, but as a paper by Alex Haxeltine and Gill Seyfang of UEA argued:

“Transition has been framed in terms of building (or rebuilding) resilience in local communities. So far, the movement seems to have successfully used resilience as a motivating framing concept. The lack of specificity used in the framing of resilience has probably contributed to resilience being perceived as an appealing goal by the wide range of citizens who have become involved with the movement”

In other words, it’s not resilience explained in the conventionally accepted way, but something about this expanded definition seems to be working, so maybe we’ll let them get on with it…

Features of community resilience

The Framework also identifies what it sees, from looking at a number of communities, as the key features of community resilience. Viewed with the slight shift in thinking that allows us to imagine it is referring to communities responding to resilience in the way set out above, it makes fascinating reading:

- “People in resilient communities use their existing skills, knowledge and resources to prepare for, and deal with, the consequences of emergencies or major incidents.

- They adapt their everyday skills and use them in extraordinary circumstances.

- People in resilient communities are aware of the risks that may affect them. They understand the links between risks assessed at a national level and those that exist in their local area, and how this might make them vulnerable. This helps them to take action to prepare for the consequences of emergencies.

- The resilient community has a champion, someone who communicates the benefits of community resilience to the wider community. Community resilience champions use their skills and enthusiasm to motivate and encourage others to get involved and stay involved and are recognised as trusted figures by the community.

- Resilient communities work in partnership with the emergency services, their local authority and other relevant organisations before, during and after an emergency. These relationships ensure that community resilience activities complement the work of the emergency services and can be undertaken safely.

- Resilient communities consist of resilient individuals who have taken steps to make their homes and families more resilient. Resilient individuals are aware of their skills, experience and resources and how to deploy these to best effect during an emergency.

- Members of resilient communities are actively involved in influencing and making decisions affecting them. They take an interest in their environment and act in the interest of the community to protect assets and facilities.

Implications and reflections

So, having read the Framework, here are some of the standout thoughts for me:

- Community resilience, they seem to be arguing, is really important, it needs to be led by communities, but there’s no money to help them with that

- The best people to organise and enable community resilience are those communities themselves

- No thought appears to be being given to how the need for enhanced community resilience, the engagement of people in this work, sits alongside the localism agenda and the Plan for Growth, and the inherent conflicts that emerge between the two

- You need to figure out yourselves what it is that you want to build resilience to

But the question for government is whether the urgent dash for growth at all costs (which they are taking to calling ‘positive growth’), could actively undermine the ability of communities to respond in the way argued for in the Framework. I was recently sent a very attractive hardback book (see right) called ‘Working together. Delivering growth though localism‘ produced by the Department for Communities and Local Government. It contains a section where the term ‘sustainable development’ is redefined thus:

But the question for government is whether the urgent dash for growth at all costs (which they are taking to calling ‘positive growth’), could actively undermine the ability of communities to respond in the way argued for in the Framework. I was recently sent a very attractive hardback book (see right) called ‘Working together. Delivering growth though localism‘ produced by the Department for Communities and Local Government. It contains a section where the term ‘sustainable development’ is redefined thus:

“‘Sustainable’ means ensuring better lives for ourselves, but does not mean worse lives for future generations, and

‘Development’ means growth. Accommodating new ways by which we earn our living in a competitive world, housing a rising population, and responding to changes new technologies offer”.

In other words, sustainable development is now any development which sustains growth. So here we have two agendas, one that is about stimulating economic growth at all costs, downplaying climate change and peak oil and removing all obstacles to large businesses doing what they like, and another which is about enabling communities to self-organise and actively respond to those things that they think reduce their resilience. Both are central to the UK government’s agenda, yet they run in complete parallel to each other, seen as entirely distinct and separate. However, if they were seen as being part of the same thing, as the Transition movement has argued, and has modelled in practice for 5 years, the benefits could be enormous. It would take only a fairly subtle shift in thinking, but it may turn out to be the thing that actually stimulates the economic activity, skills, training and investment they are presently so desperately scrabbling for.

Often flooding, and the other risks in the National Risk Register, are challenges that people don’t feel drawn do much about because they feel they are beyond their being able to usefully have an impact and they tend to be seen as issues emergency services deal with. What the Transition movement has done over the past 5 years is to bring the subject of resilience to life for people, to make it relevant, exciting even. People can sense new possibilities in the concept of resilience that weren’t there 5 years ago. It would be great if the next time this Framework is published, rather than just citing Transition initiatives as some kind of brief case study, it was able to argue that, as well as the sandbags and other elements of community emergency preparedness, an accelerated programme of economic localisation must also be a key component of any realistic programme of community resilience. Perhaps as well as the bodybags and the sandbags we also need foodhubs and SPIN farming?

The spirit of the Framework is that the onus is on communities to organise around resilience. If nothing else, the fact that Transition is now mentioned specifically creates a very useful basis for discussions with your local emergency response team, local NHS, or your local police. There is now a more common language, it’s over to us to demonstrate that the work of Transition initiatives is not peripheral, but has the potential to be central to any effective programme of community resilience. This Framework is a very useful tool for initiating those discussions that matter. As Robert Jensen argues in a piece in the latest Yes! magazine, “no political project based on denying reality can be viable for the long term”.

Brad K.

22 Nov 4:34pm

“Community resilience, they seem to be arguing, is really important, it needs to be led by communities, but there’s no money to help them with that”

That may be a Freudian slip; an unintentional affirmation of the underlying divide. Resilience is about responding to shocks. Some of the expected shocks are related to dependence on globalization and cheap energy.

I think designating money — i.e., globalization and cheap energy — for the transition is just that, a transition from here to there. Once the shock hits, then responses had best *not* depend on intact globalization, cheap energy, and an intact infrastructure dependent on cheap energy, social stability, and globalization.

Peter

22 Nov 5:14pm

In reply to the above the commenter ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^

I would suggest that resilience is a strange word to use. As how do we define it? I would say that we cannot. Why? Because we don’t know how the end of cheap oil that leads to the end of economic growth will play itself out. For example, what would really happen if the Dollar or Euro went into meltdown? The implications would be hard if not entirely impossible to forecast. What would happen to trade for various goods and services and more importantly for our food supply? How would people cope if oil spiked beyond £200 per barrel? Could the masses still commute to work? So many things would suddenly become economically unviable. Will it be a slow decent or will it be precipitous. Besides the details, we can ask one thing for sure: have we transitioned away from a globalised economy enough to meet the needs of local communities or not? It’s that simple. Because, quite frankly, if either of the two above scenarios (oil spiking too high and/or economic meltdown) play out – and there is a great likelihood they are right as I write this – then the only question will be why didn’t we transition sooner to stop millions if not billions of people from starving!?!?!?!

Local Currency is a nice and novel idea, but can they still operate when the flow of goods and service become hampered, or altogether stopped? Can Local

Currency operate without the national currency? Of course it would have to be based on a supply of goods and services at a local level to be fully self-sufficient. Also, is Community Supported Agriculture sufficient to meet the needs of those centralised in villages, towns and inner city areas. While this may be the case if a few rare places, for the vast majority the answer is an abject no. It would take many years to fully establish food self-sufficiency for Britain, using permaculture instead using the modern catastrophic, monoculture agriculture currently held in place by cheap oil.

We need to be completely self sufficient at a local, communal level. Otherwise people will starve to death alongside horrible violence and destruction. And this year has certainly shown that this has started!!! And it will for certain get whole lot worse before it gets better.

In the long term it is inevitable we will be forced to be localised instead of globalised. That’s a fact and people who are clued up enough know this without a doubt in there minds.

I know that the Transition initiatives are in the early stages, and that they are doing a flipping fantastic job of spreading the message and getting people actively engaged, but part of me asks: will it be enough it time or too little too late? I just hope that we have some crises that will wake enough people up in time to overt a horrible hellish decent. But I am sure that the weaning of humanity off of cheap, abundant energy will be varied and play out to milder and severer degrees in different parts of the world.

Unless climate change become to severe (rendering Earth uninhabitable for humans – maybe still cockroaches – which could still very well happen) we will definitely survive peak oil and the subsequent collapse of the globalised economy. But how many and it what state?

Alan Brown

22 Nov 6:05pm

Great read…. Thanks Rob.

Brad K.

23 Nov 3:42am

@Peter,

I have come to find some reassurance about Peak Oil, from TheAutomaticEarth. They find that credit contraction/economic meltdown is not only much vaster in scope than Peak Oil in the near future, but certain. So don’t worry so much about resource limitations on cheap energy.

And don’t worry about the currency so much. Cut off or even just denigrate communications outside your community or region, and you can use today’s national currency in a local sense. Trade outside your region, that might be an issue, if there is significant trade still going on at that point. It is the collapse of credit, that bubble of fictional finances that is consuming the US and Europe, that will disable globalization and disrupt access to most forms of energy. Remember that short of building wooden water wheels, most everything global needs rare earth elements only mined in China.

You touch on a topic that I hesitated to raise, persistence. Transition towns do indeed have a marvelous record of invigorating and investing people and communities with direction, spirit, and cohesion. How persistent will the Transition style leadership be, over the next few decades?

When the US was founded, the choice was made between a strong executive for responding to emergencies and strife, and a weak executive to minimize loss of focus and abuse of the system and the people. I think this is something that many, many communities will have to face, both Transition and others (maybe refer to them as “reluctant” or just “indifferent”). While the problem shocks of Peak Oil, climate change, and the ongoing economic cannibalism may play out in precipitous fashion or glacial, or variations in between, the responses will require persistent focus on long term strategies to help the most people adapt and thrive.

I find resilience to be a term that is quite appropriate to the discussion. Resilience implies continued and improved physical, nutritional, and social security. Growth, now that is a term that is becoming charged with freights of anger and angst. The biological system observation that an organism, whether individual or collective, will either grow or die, will continue to be correct and merciless. I submit that resilience and Transition are denying “growth” as defined as “produce more financial return by consuming resources or finances” from the greater world, in favor of growth as “increase security of family and community”.

Peter

23 Nov 1:32pm

@ Brad K

Yes you are right; resilience and transition are better words than the silly dichotomies of either growth or death. But I suppose life does operate like that, expansion is seen as the flourishing diversity and contraction is seen as the retraction of this. But life is still present with the same force and power (energy cannot be destroyed only changed right?) just expressed in varying ways and degrees in its cycles of expansion and contraction.

But that’s a little irrelevant for most people. People just want the warmth of really relationship, of real community. I live in a small rural village, and I recently went to London for a few days. Just being in London you really realise that we have become completely insane in the way we live. People just rushing here and there, looking totally mad – is this what life is about? It seems we are always rushing around and never sit still to feel any real peace and fulfilment.

I don’t think that the end of the globalise world will be without terrible conflicts and such like, after all its every force has and equal and opposite reaction and we are starting to feel the rebound of our mindlessly destructive action right now.

One thing for is for sure, in my lifetime (and I am 24), if I live to say 80 I will see the end of globalisation on probably all levels. Industrial agriculture will be slowed and eventually cease, forcing us to return to permaculture and forest gardening to increase out yields without the use of fossil fuel fertilisers. Most analysts seem to be on agreement that we cannot change out infrastructure to green renewables in the time need to counter peak oil and currency meltdown (which are actually happening right now). So I will very likely witness the end of national and international energy grids. Of course in 60 years, we will not have the oil that is needed to go into creating all our clothes and building materials etc, so we will have to re-learn these almost lost skills.

I feel, for want of a better word, lucky. Because at least I am among the people who have realised, like yourself/s, what is coming. And that means that there is one less person who is not asleep but ready to prepare and be of use to the wider community in which they live in a post oil world.

Steve Last

23 Nov 1:55pm

Very interesting post, especially looking at the difference between what the National Risk Register sets out compared with the World Economic Forum. Quite shocking.

I wish I’d read this yesterday before I wrote a post for my blog about Worthing’s EDAP progress. It was called ‘Measuring local resilience’ http://energydescentforbeginners.wordpress.com/

I was trying to explore the theme of resilience and getting it across to a wider audience as well as starting the ball rolling on our own set of resilience indicators. This is really helpful!

Jan Davis

27 Nov 11:13pm

Many thanks for your thoughtful and extremely useful post. I am an “emergency planner” in the conventional sense and I am sympathetic to many of the thoughts expressed. I feel there is an opportunity to connect quite different networks. I work in a borough with a diverse population. We have managed to establish a number of “Community Resilience Groups”, all with their own characteristcis and concerns. They do not label themselves as “Transition Groups” but they are concerned about and looking to the future.

The National Risk Register is the public version of the National Risk Assessment. Due to the limitations on what is traditionally within the compass of “emergency planning” might partly explain why climate change, ‘energy price volatility’, fiscal crises and economic disparity are not included in the risk matrix. Many of the symptoms, however, are included.

Every Local Resilience Forum (generally based on the geographical area covered by a police authority) has its own “Community Risk Register”. How community focussed are they? Perhaps this is a possible avenue to pursue at a more local level? Our local community resilience groups at the neighbourhood level carry out their own risk assessments where they can influence and decide on priority risks for preparation and mitigation at a neighbourhood level.

Many of the people and communities with whom I currently work are not wealthy, live locally, work locally (if they are in work), are socially active locally, many do not have cars but rely on public transport, grow food on the local allotments, already have problems paying their fuel bills (we have one of the highest rates of Winter excess deaths partly due to hypothermia) and they actively support each other across the generations at a local level through community activities such as youth clubs, lunch clubs, community associations and so on. How well are these communities able to cope with the changes ahead? How resilient are they? Perhaps the notion of “community resilience” described in the National Framework should be bolder in taking on board these likely (they are upon us now) and high impact underlying risks?

Perhaps try engaging with your local emergency planner. Say you are interested in enhancing “community resilience”. Check out and question your local “Community Risk Register”. Let the national strategic framework and the transition movement meet to influence and strengthen the resilience each is trying to achieve.

Diana Korchien

30 Nov 7:21pm

In 2010, becoming increasingly uncomfortable with the term ‘sustainable development’and its implied encouragement and acceptance of continued growth, I hit upon another phrase which I much prefer: ‘the development of sustainability’. This is the concept we should be promulgating in an era which is witnessing for the very first time the end of growth.

Larf

5 Jan 12:47pm

I would like to big-up Winter Green Theo in Dorset who has banged on tirelessly for the last few years on this subject.

He arranged for myself and others to go to a consultation seminar in Bristol organised by the home office in 2010.

Some said that engagement with such bodies would be a waste of energy and may also leave us “tainted” by association, but we clearly saw evidence of our input in subsequent documentation.

So..ya-boo-sucks to the doubters..ha!

On the subject of the limited scope of the community resilience programme in terms of percieved threats, we were told that their remit (at the time) only covered internal “threats” likely to occur in the British Isles, within the next 3-5 years.

Their vision also only went as far as preparing a community to be resilient (self reliant) for up to 3 days, (by which point presumably, the centralised support structure would be back “on-line”).

As transitioners our input can help to increase the scope and capacity of the community resilience programme, especially in terms of the inclusion of sustainable (and resilience building) techniques and technologies.

Such cross fertilisation can also help transitioners understand the wider (and possibly more immediate) implications of the need for such “community resilience”.

The programme gained much of its impetus from an incident in 2008, when the impending inundation of a power station lead to contingency planners having to contemplate the evacuation of over 500,000 people from the Cheltenham area.

Without extreme prioritisation the emergency services would have been unable to cope, a situation that would leave many communities to “fend for themselves”, for an undisclosed period, (New Orleans stylee!).

Taking this understanding of the term “resilience” into consideration may create the need for a few new categories on the re-skilling front, as much of the necessary infrastructure for such emergencies has been over centralised and under funded for decades, and so must be regenerated again at the community level.

After all, building the capacity for long-term sustainability and resilience into our community will be of little use if we’ve all had to be evacuated to the “Superdome”!

theo

7 Apr 12:19pm

principals of permaculture?

integrate not segregate?

if the govt has recognised institutional failings in its provision of resilience response capability.

(it has done and has demonstrated this in the national strategy for community resilience)

If they have identified that “the people” need to take up a precept of this responsibility themselves.

what within transition and its association to “permaculture”, prevents us from integrating with the “associative powers that be” to widen the interepretive goal posts, allow greater inclusion and understanding from a greater audience that may, under the definitions of the institution of the TT initiatives be “excluded”??

Jan

8 Apr 10:14pm

As a local authority “resilience planner” I recognise “we” do need to integrate and learn from those with concern, energy, alternative ideas – and an ability to communicate those ideas in a practical way. Often it is a case of taking opportunities when they come along – the next fuel disruption, power cut, drought or local flood – to engage with local government officers and others who are concerned about similar issues but from a very different angle and, sometimes, point of view.

Theo

10 Apr 10:09am

I appreciate there are different angles and points of view here. However if we take a fixed point of reference: a ‘defined disruptive challenge’ (fuel embargo,floods etc as listed in the National Risk Register). The scenario will determin and require a ‘unified response’ to ensure the most flexible and inclusive strategies to recover from the incideent.This will not just help to ensure ‘buisness continuum as usual’ it is to prevent trauma and unecessary suffering from the most resilient to the most at need and at risk.To my mind the arena presented by the National Strategy for Community Resilience (NSCR)presents in a nut shell a condensed microcosm of the immediate need for Transition. It is pertinatly obvious that our communities,while they do indeed have the potential for displaying capability towards resilience,will struggle to do so. It is up to all of us as to how we address this. It will have to include all variables of opinion. However, at some point we would do well to form a cohesive and flexible strategy of address. In my opinion the NSCR is a good fixing point from which to do this. I believe that the transition process and ideology will affiliate to this community process.The NSCR proposes individual and community ownership of a ‘precept of responsibility’ towards civil response to disruptive challenges. Its main stipulation is that these strategies must ‘compliment the emergency services response’. It may well be that some may not appreciate the “overarching government reach” within this, however at this stage in the interests of Permaculture ‘to integrate not segregate’ may be to our collective advantage?